By Eugene Kelly and Elizabeth Neville

Florida manatees are experiencing an unprecedented crisis and urgent action is needed to secure their future.

More than 1,000 have already died in 2021. While collisions with watercraft remain a major source of mortality, another serious and pervasive threat has emerged. Humans have polluted the rivers and coastal waters where manatees live to such an extent that the seagrasses and other submerged aquatic vegetation they depend on for food has been killed off across vast areas in Florida, most acutely in the Indian River Lagoon.

As a result, hundreds of manatees starved to death there this year.

The situation is so dire that officials from both the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission are preparing to commence a short-term experimental feeding program for manatees in part of the lagoon this winter.

Although it is illegal to feed manatees, the agencies have determined that this carefully orchestrated and well-monitored feeding program, which is designed so it will not condition manatees to associate food with people, will help reduce manatee mortality in the face of what is expected to be another crisis year.

It remains illegal for private citizens to feed manatees — don’t even think about it! — because feeding can change manatee behavior and put them in harm’s way.

Beyond this pressing food crisis, the manatees’ greatest long-term threat is loss of the natural warm water habitats they need to survive the cold winter months. Due to a thin layer of body fat (despite their rotund appearance) and low metabolic rate, manatees are vulnerable to cold stress, which can cause serious illness or death.

Over the winter months, many manatees are expected to travel to power plants along the Atlantic coast to congregate in industrial outfalls that serve as warm water refuges, and then starve to death because there is no longer sufficient aquatic vegetation around those power plants to sustain them.

Effectively, we’ve imposed a perverse choice upon many of them — death from cold stress or death from starvation. Ergo, the consideration of supplemental feeding.

The solutions are largely within our hands. Significant reductions in nutrient pollution will be essential and require an all-hands-on-deck approach because the sources of the pollution range from the fertilizers we apply to our lawns, to malfunctioning septic tanks and nutrient-laden runoff from farm fields, golf courses and urban development.

But the payoff in terms of recovery of healthy aquatic ecosystems will take time. And manatees would still face the urgent threat of their dependence on artificial warm water sources, as over 60% of Florida’s manatees depend on power plant outfalls to survive the winter.

We must look more broadly for immediate as well as longer term solutions to help secure the manatees’ continued survival by restoring essential natural habitat.

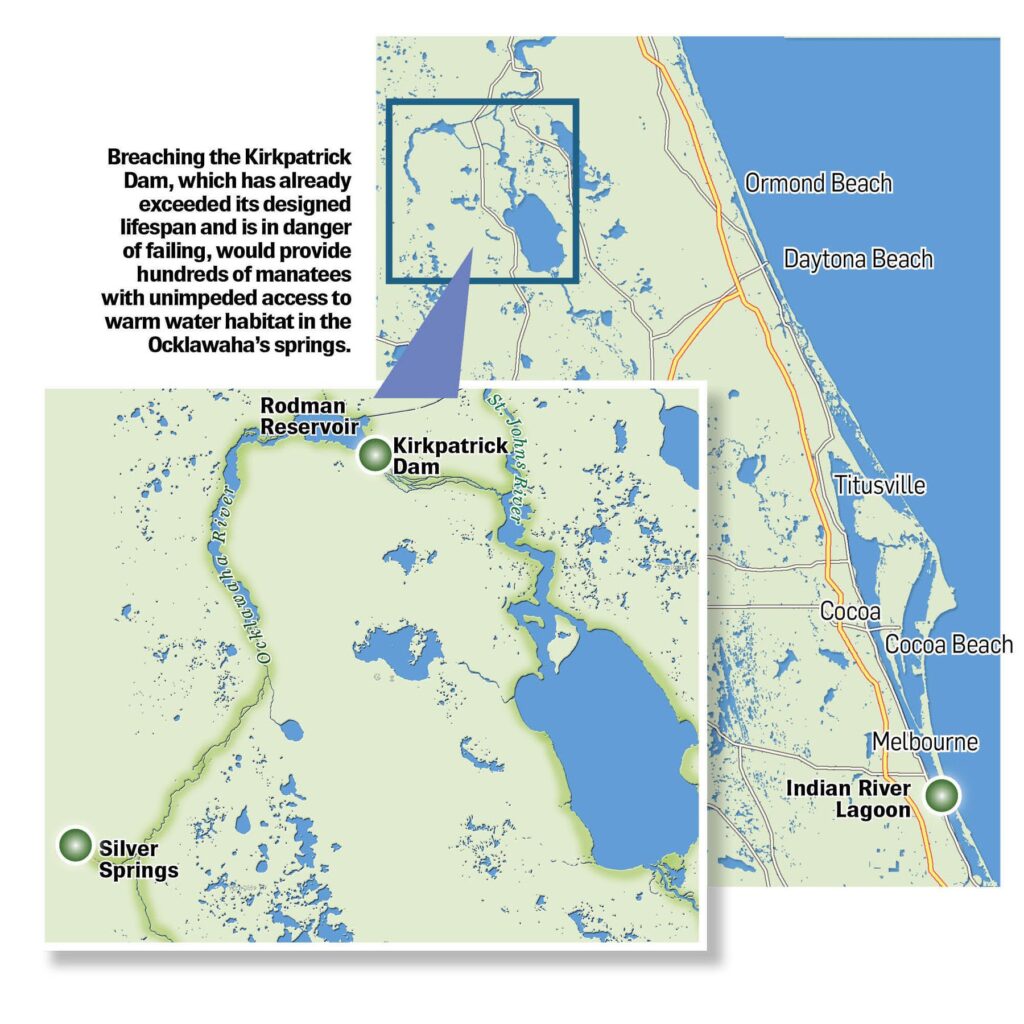

A push to restore the Ocklawaha River in north central Florida has been simmering ever since the river was dammed in 1968 as part of the failed Cross Florida Barge Canal.

Flooding from the dam created the massive Rodman Reservoir, and in the process drowned 20 natural springs and destroyed or degraded 15,000 acres of water-cleansing floodplain forest. Ever since, the dam and lock system have impeded the natural movement of manatees and other aquatic wildlife between the downstream St. Johns River and natural habitat in the Ocklawaha and Silver Springs.

While a small number of manatees manage to slip through the lock, they no longer find the warm water refuge that the Ocklawaha’s springs once afforded them.

Breaching the Kirkpatrick Dam, which has already exceeded its designed lifespan and is in danger of failing, would provide hundreds of manatees with unimpeded access to warm water habitat in the Ocklawaha’s springs and Silver Springs. It would also allow the floodplain forests to regenerate and restore more than 150 million gallons of freshwater flow to the St. Johns River every day.

The Fish and Wildlife Service has gone on record supporting restoration for its expected benefits to manatees. A public survey just completed by the St. Johns River Water Management District found that a vast majority of respondents support restoration, including those from Putnam County, where the dam and reservoir are located.

Florida’s history is replete with examples of expensive engineered “projects” that ultimately proved more harmful than helpful. Case in point, taxpayers spent $1 billion on the just-completed restoration of the Kissimmee River.

That restoration was required solely because of the millions previously spent on converting a lengthy section of the Kissimmee into a drainage canal. Thankfully, the ill-conceived Cross Florida Barge Canal project was decommissioned long before it was completed — but not before the lower reaches of the Ocklawaha were inundated by a dam that will never serve its intended purpose.

In contrast to the billion-dollar effort it took to restore the Kissimmee, restoration of the Ocklawaha would be nearly as simple as just breaching the Kirkpatrick Dam.

The Florida Native Plant Society and Defenders of Wildlife are two of the 60 organizations that compose the Free the Ocklawaha River Coalition for Everyone. We recognize that saving an imperiled species like the manatee and protecting or restoring the native plant communities that serve as their habitat are inextricably linked and mutually supportive efforts.

We need to dig deep into the toolbox, and quickly, to reverse the crisis now facing the Florida manatee. Decades of progress to recover our state marine mammal could be quickly erased. While the benefits of Ocklawaha restoration are many, it would be especially beneficial to manatees and deserves to be elevated as part of the discussion.

Eugene Kelly is Policy and Legislation Chair of the Florida Native Plant Society. Elizabeth Neville is Senior Gulf Coast Representative for Defenders of Wildlife.

“The Invading Sea” is the opinion arm of the Florida Climate Reporting Network, a collaborative of news organizations across the state focusing on the threats posed by the warming climate.