An interview with Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, University of Miami Distinguished Professor of Architecture

As part of its series “The Business of Climate Change,” which highlights the climate views of business men and women throughout the state, The Invading Sea spoke with Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, director of the University of Miami’s Master of Urban Design Program and the Malcolm Matheson Distinguished Professor of Architecture. Elizabeth is a co-founder and principal of the architecture and town-planning firm DPZ CoDesign, which is headquartered in Miami.

Here are some highlights from the interview.

You’ve been working and designing in Miami for decades and have taught at the University of Miami since the 1970s. What kind of climate-related changes have you witnessed during that time?

I think probably most of us who’ve been around that long have seen many changes in the natural environment. I think it’s very clear that the water levels look different in the canals or wherever we might be encountering them.

Perhaps that’s the power of suggestion. I don’t know about that. But certainly I think some erratic weather contributes to that and I think it does need to be acknowledged that the power of suggestion and climate change is very strong and that sometimes much is being ascribed to it that may not be occurring.

But I do think everyone down here by now is aware that we have something to contend with, and the measurements of the 10 inches in the last century and the predictions of acceleration of change are all kind of information that we’re learning how to deal with.

How have climate change and sea-level rise affected the way architects approach design in coastal communities?

I would say that most of us became aware in the last decade that this was going to be something to contend with. It’s not that the knowledge didn’t exist before, but I would say probably many of us were just not aware of it. I would say one of the people who brought it to our attention first was Harvey Ruvin with some of the committees and task forces that he set up to address it.

It took even more than those beginnings before the architects began to realize that perhaps the kind of levels, the floor elevations that we were designing to, according to the regulations, maybe would not be adequate, even in the short- or mid-term.

FEMA’s design elevations are going to be changing in the next year or so, and already I think most architects are working to those. You might hear the term “freeboard” sometimes used, and that refers to really something the architects started asking municipalities to do.

(That enables) the zoning codes to allow for some extra height so that you could make a taller ground floor, or a taller first floor that could accommodate being raised for increasing flooding in the future, and so many codes already have that kind of freeboard flexibility in them.

Have building codes and design standards kept up with the changing climate?

They’re starting to. If all buildings were net-zero right now and so were our automobiles, it would take 30 years for the change to level off; the scientists will tell you that. So the impacts will continue, and so we might expect, no matter how much we try, that we’re still going to be dealing with additional heat, additional flooding, maybe storm intensity, and so on, and the codes are really just beginning to deal with that.

Freeboard…is one of those things, but we probably need to look at the location, zoning codes, zoning districts, and how we’re dealing with the specific areas that are likely to be flooded, and I presume we’re going to be doing that in the near future. Miami Beach has already, I think, set a good example in that sense.

What makes a particular design more resilient or less resilient?

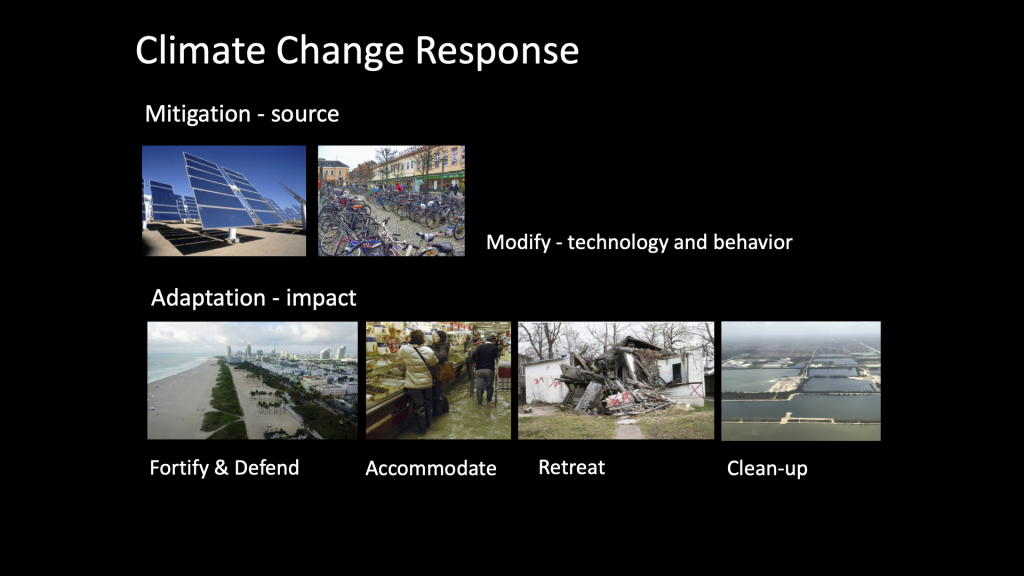

I attach sustainability to mitigation, and resilience can be attached to adaptation. And so it’s really about being able to withstand the stresses and the impacts, which have also been identified as dual, chronic stresses and catastrophic.

And so the chronic stress of just the groundwater rising because of sea-level rise that we can see, and flooding of water back-flowing, as we used to see in Miami Beach, is one kind of thing to deal with.

(Then there is) storm surge and the kind of catastrophic winds that a hurricane brings. That needs a different kind of response. So I think we have to be ready for both of those things.

I think not only of buildings but of public spaces, you know, our streets and public-space networks, and so that response to the chronic stresses of flooding might be some de-paving, making pavements permeable and giving percolation more space.

The response to the surge might be to either allow the water in and try to get it out quickly with pumps. Or we’ve seen a very interesting proposal from the Army Corps of Engineers to build a wall around downtown Miami, which I think is not a great idea. Once the water gets past that wall, it doesn’t have a way of getting out.

What should designers and planners be doing differently?

We should always be designing for the long-term. If we don’t want to be continuing to create emissions through the waste of repeatedly rebuilding—taking down a building and putting up a new one every 20 or 30 years, whatever the life of its mortgage value is.

One of the things we should be doing is building for the long-term and imagining that we want to use resources wisely. And in that case, we need to be prepared in an adaptive way for the resilience that’s going to be required. I think that’s an obvious approach, and then there might be the argument that maybe we should be picking up and leaving at a certain point; it costs money to be that resilient.

Maybe we should be building temporarily and understand that there’s a short life in some areas. It’s always a kind of geographic determination. It’s not one size fits the whole region. I think we need, in both cases, to think about: how do we discard or clean up after the use?

That’s something that very little thought is being given to. But we do need to be thinking about what is that endgame of not just how do we get to the end of some financial aspect of the built environment, but also what do we do, how do we pay for cleaning it up afterwards. And we have natural resources underneath our buildings here that could help pay for that, but I don’t think we’ve yet really come to terms with that.

Kevin Mims, a Florida-based freelance journalist, is the producer of “The Business of Climate Change.” He conducted this interview with Ms. Plater-Zyberk.

“The Invading Sea” is the opinion arm of the Florida Climate Reporting Network, a collaborative of news organizations across the state.