By Kristina Dahl, Union of Concerned Scientists

Last year, Florida House Speaker José Oliva made the scientifically unsupported claim that Miami Beach’s buildings and infrastructure are causing the underlying land to sink and its streets to flood with seawater.

Last week, the Florida Legislature soundly rejected such claims and affirmed the need to address climate change and sea-level rise — the primary cause of Miami Beach’s high-tide flooding— by passing Senate Bill 178. This bill requires public projects along the coast to prove there’s no future flood risk in order to use taxpayer dollars for construction costs.

Meanwhile, House Bill 1157, which would establish an initiative to study land subsidence (another word for sinking) throughout Florida, is making its way through the legislature. While it’s true that most of Florida’s coastline — like much of the Eastern Seaboard—is subsiding, data indicate that for much of the state, the rate of that subsidence pales in comparison to the rate of climate change-driven sea-level rise.

Overly focusing on subsidence in Florida distracts from the real and urgent challenge that lies ahead as sea level rises.

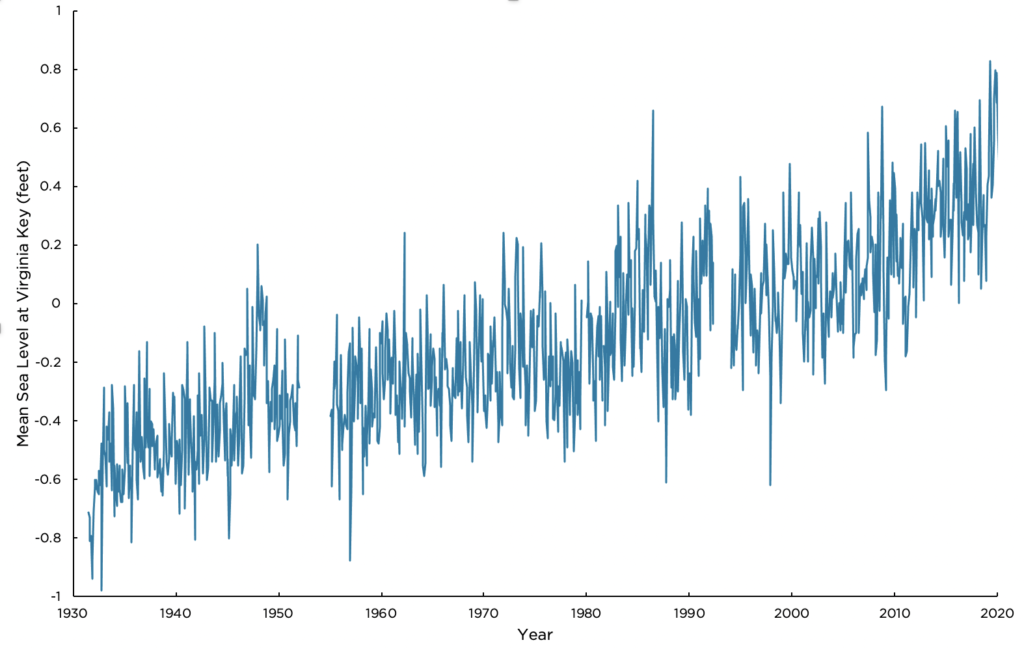

Sea-level rise and land subsidence can both increase the risk of flooding in coastal areas. Measurements show that the rate of land subsidence in Florida varies from place to place but is generally less than 0.5 millimeters per year.

At about 1.7 millimeters per year, the global average rate of sea-level rise over the course of the 20th century was more than three times that of land subsidence in Florida. What’s more, for the last 25 years, the global rate of sea-level rise has been even higher—in excess of 3 millimeters per year.

It doesn’t sound like much, but when you add it up, sea levels have risen by an average of more than 3 inches globally since 1993. Those extra inches have contributed to a fivefold rise in the frequency of high-tide flooding across the nation, including in Florida and other states in the Southeast.

Only in limited areas— such as specific parts of Miami Beach that were built with filled sediment that is slowly compacting over time — does the rate of subsidence approach parity with that of sea-level rise.

With the passage of SB 178, Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection will be tasked with developing a standard for how future flood risk is assessed for potential construction projects. A key part of that standard will be ensuring that the latest science on sea-level rise is incorporated into each study.

Fortunately, the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact has updated its sea-level rise projections for Florida using the best available data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Those projections indicate that the state can expect 21 to 54 inches of sea-level rise by 2070.

According to research my colleagues and I have done, that amount of sea-level rise would put more than half of Miami Beach’s homes at risk of flooding 26 times per year or more. For comparison, at its current average rate for the state, land subsidence in the next 50 years would add up to just one inch—a small fraction of what the state expects as a result of climate change.

Nevertheless, land subsidence research initiatives across the U.S. have illuminated areas that are particularly at risk as sea level rises, and the same may be true for Florida. Detailed measurements of land subsidence in the San Francisco Bay Area published in 2018, for example, highlighted that the combination of land subsidence and sea-level rise is creating risks for parts of the Bay shoreline that are greater than had originally been thought.

Tens of thousands of homes in Florida are at risk of chronic flooding in the coming decades. In implementing SB 178, the state will be helping to ensure that future public development does not add to the problem by putting even more homes, businesses, and facilities in harm’s way.

Updating the state’s flood maps to incorporate future sea-level rise and allocating resources to building the flood resilience of Florida communities would also help the state to prepare for what lies ahead. While measuring land subsidence rates could help to refine communities’ plans, it must not distract from the truly existential threat that climate change-driven sea-level rise presents to the residents of Florida’s coasts.

Kristina Dahl, Ph.D., is a senior climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists and author of the scientific report “Underwater: Rising Seas, Chronic Floods, and the Implications for US Coastal Real Estate.”

“The Invading Sea” is the opinion arm of the Florida Climate Reporting Network, a collaborative of news organizations across the state focusing on the threats posed by the warming climate.