This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

By Amy Green, Inside Climate News

CEDAR KEY, Fla. — Timothy Solano could feel the dread rise within him as he sat with his wife and three young children in the family’s Cadillac Escalade on the two-lane causeway leading into this island fishing village on Florida’s Gulf Coast.

Floodwaters had left the road ahead impassable, and Solano, a clam farmer for the family-owned business his father established nearly 30 years ago, could only speculate about the damage lying beyond what he could see.

Overnight, Hurricane Helene had swirled ashore some 95 miles northwest of here as a massive, fast-moving category 4 storm, packing winds of up to 140 miles an hour. In the waning days of September, the hurricane would carve a vast swath of destruction from Florida to western North Carolina, causing catastrophic flooding across southern Appalachia.

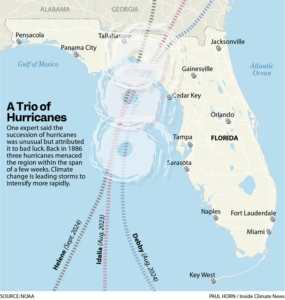

For Cedar Key, Helene was the third hurricane in 13 months. Idalia made landfall near here in August 2023 as a category 3 hurricane; about a year later, Debby hit the region as a category 1 storm. Milton would strike southwest Florida a mere 13 days after Helene as yet another category 3 storm, although that system would cause only minimal impacts in this part of the state.

Helene was the most catastrophic for Cedar Key. On some parts of the island, the hurricane unleashed a storm surge of at least 12 feet. Some residents still were rebuilding from Idalia when Debby passed over, and they were cleaning up from Debby when Helene arrived.

This extraordinary succession of hurricanes has left the tiny island village with an enormous reconstruction effort and an existential crisis. The future that collectively had been imagined by residents here, based on previous environmental patterns, effectively has been washed away, and a vision for what’s next has yet to gain consensus.

Can Cedar Key rebuild and still retain the old Florida charm that has set it apart from other coastal areas characterized by towering condos? In what ways can residents rebuild to better withstand the future storms and sea level rise that are inevitable? Could wealthy out-of-town investors swoop in and make over the community? The key to the town’s fate can be found in the hard-scrabble resilience of its residents.

Solano, 28, considered his own outlook as he sat at the wheel of the family’s car, surrounded by his wife, then-5-year-old son, 3-year-old daughter and baby daughter, not yet 1. He feared the family clam business was gone.

“I was worried I wasn’t going to be a clam farmer anymore,” he would recall.

‘Things are changing’

Cedar Key sits three miles off the coast of Florida’s sparsely populated Big Bend region, so named for the way the peninsula meets the panhandle here.

The community, home to some 700 residents, is characterized by quaint historic cottages, with a town center consisting of pastel-painted shops and restaurants, some of which have reopened since Helene. The city hall was moved after Idalia to higher ground.

“You have no idea what it’s like to take your clerk’s office, your records, your city hall, your entire police department, and move it every time there is a warning,” Cedar Key Mayor Sue Colson said. “Do you know how disruptive that is? And crazy it is?”

Colson, 78, is a retired hospice nurse who in addition to serving as mayor also directs the Cedar Key Food Pantry and works at the Cedar Key Chamber of Commerce.

“I know when to recognize when things are terminal and when they’re not, and I also want the best use of life while you have it,” she said. “There may be hope, but you don’t want to get hung up on the hope to where you’re not realistic.”

Raised on Long Island, N.Y., Colson moved to Florida when she was 16 and eventually met her husband, a fifth-generation Floridian whose father was born in Cedar Key. The couple came here about 30 years ago so he could take up clam farming. Colson now moves slowly and walks with a stoop, but her manner is direct and no-nonsense. She never plans on leaving Cedar Key and eventually wishes to have her ashes scattered in the Gulf of Mexico.

“You can’t quantify that,” she said. “That’s something that’s either with you or not.”

Across the island debris piles loom, composed of large tree trunks and the splintered remains of homes and businesses. Helene destroyed or damaged at least 40 houses. The waterfront establishments were also badly damaged, and some were washed away entirely. With the grocery store still closed, the nearest supermarket is some 50 miles away. Still, life has carried on in this small town, where there are no traffic lights and lots of people get around on golf carts.

Several federal and state preserves line the coast in this region, with relatively pristine waters that support a thriving tourism industry based on boating, fishing and other outdoors activities. The crystalline waters also are ideal for Cedar Key’s clam production, which accounts for more than 80% of the state’s shellfish aquaculture industry (consisting of clams and oysters). Primary draws in Cedar Key are the fresh seafood and stunning sunsets.

Forecasters had expected the 2024 hurricane season would be extraordinarily active, thanks especially to unusually warm sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea. The season, which ended Nov. 30, featured 11 hurricanes, including five that made landfall in the continental U.S., according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. A typical season produces seven hurricanes.

This was no typical season. It got off to an explosive start in July with Beryl, the earliest category 5 hurricane on record in the Atlantic basin. Beryl caused significant flooding in Texas and Louisiana after making landfall near Matagorda, Texas, as a category 1 storm.

Seven hurricanes formed after Sept. 25, the most on record for this time period. Helene was directly responsible for more than 150 fatalities, making it the deadliest hurricane to affect the continental U.S. since Katrina in 2005, NOAA said. Most of the deaths were in North Carolina and South Carolina, although the storm caused widespread wind damage from the Gulf Coast to the North Carolina mountains and storm surge flooding across western Florida. Climate change increased Helene’s peak rainfall totals by 10%, according to scientists at World Weather Attribution, an organization that quantifies how climate change influences extreme weather.

Milton’s rate of rapid intensification, a phenomenon that is becoming more common as the global climate warms, was among the highest ever observed. The hurricane underwent a 90 mile-an-hour increase in wind speed within 24 hours, reaching category 5 strength twice with winds topping out near 180 miles an hour, before losing strength in advance of making landfall. Milton caused a destructive storm surge across southwest Florida, the outbreak of 46 tornadoes statewide and torrential rainfall and flooding, with rainfall amounts of at least 10 to 15 inches.

Despite being spared the worst consequences of Milton, Cedar Key faces additional threats. The local sea level has risen nearly six inches since 1992, and a NOAA tide gauge recorded the fourth-highest rate of sea level rise acceleration in the nation here in 2020, according to the community’s vulnerability assessment. It cited the town’s low topography, aging infrastructure and high exposure to the Gulf of Mexico as concerns.

“Things are changing here,” Colson said. “When you live on an island you’re attuned to the weather and to the tides and to the seasons much more than the average person.”

By 2040 even a moderate storm or extreme high tide could affect as much as half of the island’s critical infrastructure, including the school, fire station, post office, library and food pantry, the vulnerability assessment predicted.

The low-lying town center with its gift shops and restaurants serving fresh steamed clams is especially exposed, Colson said. The community is considering moving to a mixed-use model so that certain important establishments could be relocated to higher ground, but some residents have doubts about living right next door to a supermarket. There also are concerns amid the reconstruction efforts about whether Cedar Key could lose its small town charm, but residents also are worried about their properties losing value. Many do not want to move away, but they also are struggling to accept the profound changes in store, Colson said.

“This hurricane helped them get a little closer to realizing what’s going to happen,” she said.

“From this storm you’re going to have innovation. I have great hope,” she continued. “People will leave if they can’t hack it.”

An expression of agency

Dell Weible knows how to rebuild after a hurricane. He has done it three times before.

His two-bedroom cottage already had hurricane damage when he bought it six years ago. He renovated the house with love and care, only to have Idalia flood it again. Within a month and a half he had the house repaired, but several months later Debby blew through.

While Debby howled and the water rose, Weible hunkered down inside the home. At one point he could hear two cats drowning beneath the dwelling, which was perched on two-foot pilings. He cut a hole through the floor, rescued the cats and spent the rest of the night with them on his bed, watching the home fill with a foot of water. In the darkness, the water glowed blue with bioluminescence, illuminating the whole house. Weible wound up keeping the cats. They go by the names Ethel and Ron, or sometimes Paco and Nacho.

“I actually thought I was losing my mind for a second,” he said. “It was kind of fun.”

Nothing would compare with the violence of Helene. The storm sent a rush of water so powerful it pushed his neighbor’s house from its foundation, sending the home crashing into his own. The force in turn knocked his house off its foundation. Weible was not home at the time, having evacuated inland to Gainesville, where he ended up staying for two weeks with family friends. A coffee shop he owns next door also was severely damaged.

Weeks later, standing inside the gutted living room of the cottage he had restored so many times before, he felt stoic. The house was uninhabitable. Some of the walls were partially ripped out, the palm-print wallpaper peeling. Holes in the floor made just walking around difficult. He was living in a trailer parked outside provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

“The truth is I’ve done this enough I don’t look back. I look forward. I just look at things as they are, and you make the best of a bad situation. I don’t think emotions come into play anymore. When you deal with enough stuff like this,” he said, “it’s more of a financial outlook.”

He planned to rebuild the structure a fourth time and turn it into a bar. Meanwhile he would move into a historic cottage that also was damaged during Helene, which he would relocate to the now empty pilings left over from the house that had slammed into his own.

He would raise the cottage, which already had been on pilings, another two feet and refurbish it with materials such as stainless steel, so that the next time he just could hose it out. He also planned to tie the cottage down more tightly, making it harder for another storm to dislodge it. He would also repair the coffee shop next door and turn it into an ice cream shop.

For Weible, 41, many of his neighbors feel like family. He also owns Cedar Key Adventures, a business providing kayak, bike and golf cart rentals.

“I’m flipping a coin, but I’m going to build the best I can,” he said. “I like living here, and I’m willing to deal with the storms as long as I can make a living. I’m not going to leave until my last dollar runs out.

“It isn’t fun. It’s like I just turned back the clock on my life a half-a-decade,” he said. “I’m definitely financially set back five years because of this storm.”

The reasons why people affected by chronic climate impacts move or stay are complex and not well-understood, said Matt Hauer, an associate professor specializing in climate migration in the Department of Sociology at Florida State University. Some have plenty of resources to rebuild while others may lack the means to move. Some wish to remain with social networks.

“There is a stickiness about places,” he said.

A 2023 study, citing Indigenous peoples and islanders as examples, found that some individuals are more likely to stay when they feel deeply connected socially and culturally with a place and believe they can adapt to future hazards. The study characterized these decisions as an expression of the person’s agency in the face of environmental risk. For instance in the Pacific island nation of Tuvalu, residents tended to stay for cultural and spiritual reasons. But their resolve to remain also was aimed at raising awareness about climate impacts and the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, which are accelerating the planet’s warming.

In Florida, communities like Cedar Key can access funding for vulnerability assessments and adaptation projects under the state’s Resilient Florida program. Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, implemented the $1.8 billion program in 2021, and his administration has touted it as a historic investment toward preparing communities for rising seas, more damaging storms and flooding.

Three years later the governor signed legislation erasing several instances of the words “climate change” from the state code. The measure restructured Florida’s fossil fuel-based energy system around reducing reliance on foreign sources rather than moving toward cleaner energy, which would help slow warming and ideally ease impacts such as hurricanes. After Milton, DeSantis seemed to dismiss the role of climate change in the storm’s intensity altogether, appearing to discount at least one impact his Resilient Florida program was designed to address.

“There’s nothing new under the sun,” he said during a briefing in tornado-torn Fort Pierce, in southeast Florida. “This is something that the state has dealt with for its entire history, and it’s something that we’ll continue to deal with.”

Caryn Stephenson, a 23-year Cedar Key resident, raised four children with her husband here. She is involved in multiple businesses, including two gift shops and a seafood market.

“Cedar Key is known for its resiliency, and what happens here after a storm, it’s really a beautiful thing. It’s very community-based, neighbor helping neighbor, business helping business,” she said. “It’s super-hot and terrible. The town is a muddy, muddy mess. But everyone comes together.”

The gift shops are situated in the town center, in a building dating to 1872 and constructed of oyster shell, lime and water. Before opening the shops in 2023 she and her business partner essentially had a new building constructed inside the old one, to meet contemporary codes. The workers raised the shops by two feet and used materials like concrete so that the shops could easily be hosed out after the next flood. In advance of Helene, the shops’ employees packed all the merchandise onto U-Haul trucks, drove it away and boarded up the building’s historic windows. The employees were able to reopen the shops within a few weeks after the hurricane.

Stephenson also works in real estate and is engaged in a business offering short-term vacation rentals. Her husband is a clam farmer, and together they own Southern Cross Sea Farm. The problem now is customers, she said. Tourism here still has not returned to pre-Idalia levels, a hardship for homeowners and property managers like herself but also the housekeeping staff, many of whom don’t live locally or qualify for disaster relief programs. They have been laid off.

She has listed a few homes for residents who don’t wish to go through another hurricane, but she believes most will stay. Her own home, on 15-foot stilts, suffered only minor damage, although Helene’s storm surge passed a breathtaking three feet beneath the house.

“Three storms in 13 months. You gotta think something is changing, or we’re just having a really bad string of luck,” she said. “I want to believe it’s a fluke and not a trend. But also the practical side of me says we should be prepared for more in the near future. And while we hate that, we can also take it upon ourselves to prepare and do better than we have been.”

A passion for clams

Timothy Solano and his family evacuated to Gainesville for Helene. Overnight a tree dropped on the roof of the house they rented, and another fell on the fence outside. At daybreak, he and his wife readied the children, and by 8 a.m. the family was headed back to Cedar Key.

Solano is among some 200 clam farmers here. Some work independently, running small operations. Others, like Solano, are part of bigger wholesalers. Cedar Key Aquaculture Farms is one of Florida’s largest clam wholesalers, selling during a normal year nearly 25 million of the mollusks to Costco stores from Miami to Massachusetts. Solano’s brother is general manager, his sister serves as the office manager and his younger brother oversees all the bags the farmers use to raise their clams offshore. Solano supervises the water operations.

Idalia already had left the business depleted. The farm lost so many clams to that hurricane the business had resorted to buying the mollusks from outfits in Georgia, just to keep orders filled.

“There’s been nights where I have been so defeated, where I break down to my wife,” he said. “I am worried about putting my kids in a bad position because I’m trying to be a farmer. My parents gave me a great life, and I am trying to fill big shoes.”

Solano brims with passion for clam farming. “They’re really like kids to you,” he said of the mollusks. He relishes watching them grow.

He testified before the Florida Legislature after Idalia about the plight of farmers such as himself, who in recent years also have weathered losses to the unusually warm water in the Gulf of Mexico. Solano also has met with other elected officials such as Sen. Marco Rubio, a Republican who President-elect Donald Trump has named as his choice for secretary of state, when Rubio visited Cedar Key after Helene.

After the family was turned back by Helene’s floodwaters outside of town, “the first thing I did was I grabbed a beer,” Solano said. Then he and a few other farmers ventured out on a boat to assess the damage to their clams. The farmers encountered debris everywhere and proceeded slowly, worried that if they hit the debris they could be catapulted off the boat. Solano lives on the mainland, and the family’s house was not severely damaged.

The clams had suffered a heartbreaking fate. Not only had Helene’s storm surge immersed them in mud, the rush of water, as it withdrew from Cedar Key, also had buried them in debris. The farmers still were cleaning up from Idalia and Debby, and now they faced their biggest job yet.

“It looks like a bomb went off out there and threw everything around. When I went out there I definitely got teary-eyed because I’ve got three kids, and I have put everything into this farm,” he said. “It’s just so heartbreaking because you work so hard.”

The work after a hurricane is back-breaking, involving lifting heavy bags of clams out of the water and tending to them while dealing with debris and wildlife such as stingrays. Solano estimates the business lost as much as 80% of its annual harvest, worth up to $3 million.

A few of the younger farmers are getting out, but Solano plans to stick with it, at least for now. While residents on the island work to rebuild to be more resilient, he said there is little the farmers can do to help their clams better withstand the next storm. His business plans to put hurricane relief funding toward constructing a sturdier processing facility on the mainland.

“Mother Nature, she’s going to do what she wants to do, and we’re in her world so we have to work with her. We can’t change her,” he said.

“I love clam farming. I don’t see myself doing any other job, and that’s why I’m fighting tooth and nail,” he said. “We’ve worked so hard to get to where we are right now. There is no way we’re throwing in the towel. They would have to throw in three more hurricanes.”

Amy Green covers the environment and climate change from Orlando. She is a mid-career journalist and author whose extensive reporting on the Everglades is featured in the book “Moving Water,” published by Johns Hopkins University Press, and podcast “Drained,” available wherever you get your podcasts. Amy’s work has been recognized with many awards, including a prestigious Edward R. Murrow Award and Public Media Journalists Association award. Banner photo: Large piles of debris remained in Cedar Key, some two months after Hurricane Helene hit (Credit: Amy Green/Inside Climate News).

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. To support The Invading Sea, click here to make a donation. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.