These days, it’s hard to escape news stories discussing how climate change is contributing to extreme weather disasters, including the recent U.S. hurricanes. Aid agencies are increasingly worried about the widespread damage.

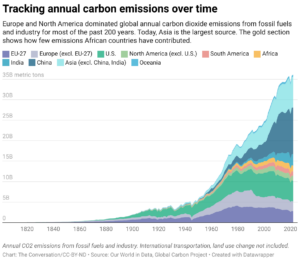

A growing question as these disasters worsen in a warming world is how to pay for recoveries, particularly in poorer countries that have contributed the least to climate change.

I am a climate scientist who researches disasters, and I work with disaster managers on solutions to deal with the increasing risk of extreme events. The usual sources of disaster aid funding haven’t come close to meeting the need in hard-hit countries in recent years. So, groups are developing new ways to meet the need more effectively. In some cases, they are getting aid to countries before the damage occurs.

Disaster aid funds aren’t meeting growing need

Countries have a few ways that they typically send money and aid to other countries that need help when disasters hit. They can send direct government-to-government aid, contribute to aid coordinated by the United Nations, or support disaster response efforts by groups like the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement.

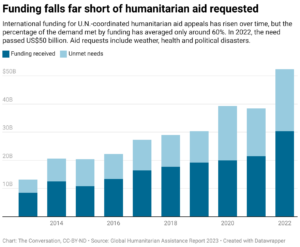

However, the support from these systems is almost never enough.

In 2023, the amount of humanitarian funding through the U.N. was about US$22 billion. The U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimated that countries hit hard by disasters actually needed about $57 billion in U.N. humanitarian aid. This does not even include the costs borne directly by disaster-affected people and their governments.

To help address damages specifically from climate change, the global community agreed at the U.N. climate conference in 2022 to create a new method – a Loss and Damage Fund. Loss and damage is generally defined as consequences of climate change that go beyond what people are able to adapt to.

The goal of the fund is for countries that historically have done the most to cause climate change to provide funding to other countries that did little to cause it yet are experiencing increasing climate-related disasters.

So far, however, the Loss and Damage Fund is tiny compared to the cost of climate-related disasters. As of late September 2024, total pledges to the Loss and Damage Fund were about $700 million. According to one estimate, the costs directly attributable to climate change, including loss of life, are over $100 billion per year.

One goal of the 2024 U.N. climate conference, underway Nov. 11-22 in Azerbaijan, is to increase those contributions.

Sending aid before the disasters hit

In response to these growing needs, the disaster management community is getting creative about how it helps countries finance disaster risk reduction and response.

Traditionally, humanitarian funding arrives after a disaster happens, when photos and videos of the horrible event encourage governments to contribute financial support and a needs assessment has been completed.

However, with today’s technology, it’s possible to forecast many climate-related disasters before they happen, and there is no reason for the humanitarian system to wait to respond until after the disaster happens.

A global network of aid groups and researchers I work with has been developing anticipatory action systems designed to make funding available to countries when an extreme event is forecast but before the disaster hits.

This can allow countries to provide cash for people to use for evacuation when a flood is forecast, open extra medical services when a heat wave is expected, or distribute drought-tolerant seeds when a drought is forecast, for example.

Insurance that pays out early to avoid harm

Groups are also developing novel forms of insurance that can provide predictable finance for these changing catastrophes.

Traditional insurance can be expensive and slow to assess individual claims. One solution is “index insurance” that pays out based on drought information without needing to wait to assess the actual losses.

African nations created an anticipatory drought insurance product that can pay out when the drought starts happening, without waiting for the end of the season to come and the crops to fail. This could, in theory, allow farmers to replant with a drought-resilient crop in time to avoid a failed harvest.

Without insurance, disaster-affected people usually bear the costs of disaster. Therefore, experts recommend insurance as a critical part of an overall strategy for climate change adaptation.

Boosting social protection systems

Another promising area of innovation is the design of social services that can scale up when needed for extreme weather events.

These are called climate-smart social protection systems. For example, existing programs that provide food for low-income families can be scaled up during and after a drought to ensure that people have sufficient and nutritious food during the climate shock.

This requires government coordination among the variety of social services offered, and it offers promise to support vulnerable communities in the face of the rising number of extreme weather events.

Future of the Loss and Damage Fund

To complement these innovative disaster risk finance mechanisms, aid from other countries is crucial, and the Loss and Damage Fund is a key part of that.

There are still many areas of debate around the U.N.’s Loss and Damage Fund and what counts as true financial support. There have been discussions over whether investing in a country’s resilience to future disasters counts, whether existing financial systems should be used to channel finance to countries in need, and what damages are truly beyond the limits to adaptation and qualify.

The new Loss and Damage Fund is only of a part of a mosaic of initiatives that is seeking to address climate disasters.

These novel mechanisms to finance disaster risk are exciting, but they ultimately need to be created in conjunction with investments in adaptation and resilience so that extreme weather events cause less damage when they happen. Communities will need to plant different crops, build flood drainage systems and live in adaptive buildings. Managing climate risk requires a variety of innovative solutions before, during and after disaster events.![]()

Erin Coughlan de Perez is a professor of climate risk management at Tufts University. Banner image: In 2015, the Uganda Red Cross used early storm forecasts to send workers to distribute thousands of water purification tablets, water storage containers and other items to people in rural areas likely to be flooded by the storm. (Denis Onyodi/URCS-Climate Centre, CC BY-NC).

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. To support The Invading Sea, click here to make a donation. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.