By Barbara Drake-Vera

Sifting through the wreckage of a hurricane teaches you the fragility of life in today’s Sunshine State.

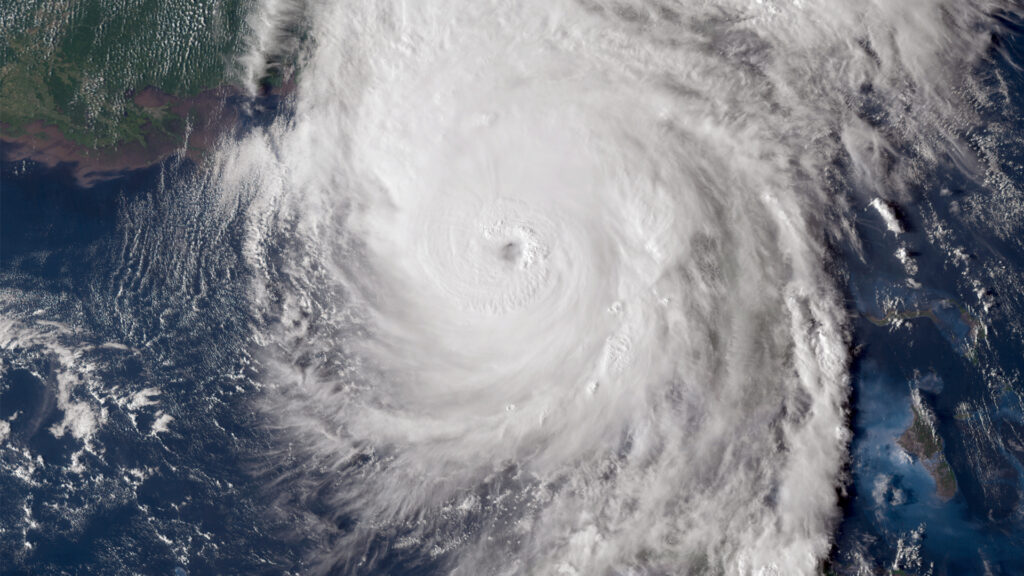

A monstrous, fast-moving Category 4 hurricane, Helene formed in the overheated Gulf of Mexico in late September and made landfall on the Sept. 26 near Perry, Florida, 90 miles from my home in Gainesville, before plowing through five more states, leveling towns and infrastructure, and killing upward of 150 people.

My husband, Jorge (a former director of emergency services for the American Red Cross in Miami), and I tracked Helene’s stomach-churning path northward off the coast of Florida for three days before she plowed ashore. A slight wobble east would mean even greater destruction for coastal towns, already bracing for catastrophic storm surge, as well as for those inland.

Helene was aiming straight for Tallahassee, and it appeared that nature was rebutting the governor for signing legislation to remove the words “climate change” from state law, effective July 1 of this year.

Intensified by That Which Shall Not Be Named, abnormally hot Gulf waters fueled Helene’s astonishing growth from Cat 1 to Cat 4 status in just 24 hours. She was 500 miles wide before landfall — wider than our state’s peninsula — and Jorge and I knew that wherever her eyewall passed, we and our neighbors would not be spared her wrath.

On the morning after landfall, we emerged from our powerless, black cocoon of a house to find gusty blue skies and idyllic sunshine, the once-silent birds chirping again. Our backyard was filled with the wreckage of our neighbor’s gum trees, which had snapped in the high winds and landed just feet from the wall of our breakfast nook. Part of our fence was down. Strangely, the ground was not very wet for a major hurricane.

We knew we were very, very lucky.

After a grueling day of cleanup, we walked through the neighborhood, stepping over downed limbs and piles of debris. There was that familiar, giddy sense of post-hurricane relief — We made it! We survived AND didn’t lose the house! — mingled with sorrow and dread. Helene was doing something Gulf-made hurricanes don’t normally do. She had saved her warm rains for states to our north, triggering floods of biblical proportions, particularly in eastern Tennessee and western North Carolina.

I had seen on social media the videos of entire homes being swept away, of desperate families stranded on roofs, of people in cars being rescued or of cars just sinking, beyond the reach of good Samaritans. The videos were taken on people’s cell phones, and in most, the victims’ cries for help were not audible. Just the astonished commentary of onlookers.

“Oh, my god, that house is floating away. That man, his car. Should we go help? No, the waters are too high. You’d never make it back. But …”

As we gingerly made out way past a wooded lot, Jorge stooped to examine a broken-off tree limb, ripped from a live oak. Scabbed with grey bark, the lightweight log was about 2 feet long and 8 inches around, with an elongated crescent at the bottom where the limb had snapped. A foot above that were a pair of smaller round openings, obviously the work of some woodland creature.

“It’s a woodpecker’s home,” he said, pointing to the dead wood riddled with beak holes.

He stood the limb upright and shone a flashlight inside. The tall hole at the bottom had room for several woodpeckers. The squarish hole above that was deeply chiseled. The smaller, perfectly round hole on top had been newly pecked, as evidenced by the fresh wood scrapings. It was separated from the hole below by a level platform, i.e., a floor.

“It’s a condo!” said Jorge, feeling inside.

I dug two fingers in the top cavity. There were no feathers, no eggs. Just rough-hewn walls. That gaping hole at the bottom must have been where the family lived.

“And it comes with its own turkey mushroom,” he added, flipping the limb to reveal a flat, brown fungi, still intact.

“Let’s keep it,” I said, taking the log.

We strolled back to our house in the gathering dusk. I wondered about the bird, likely male, that had labored over this well-used home. Had he been preparing the top floors for a future family? Had he and his mate lived in the hole on the bottom while working on the upper floors? What had happened to them when Helene’s outer bands hit? Had they tumbled from their shelter as the branch split and crashed into the undergrowth? Were their dead bodies back there? Or had the woodpeckers heeded an instinct to evacuate, unlike some humans along the Big Bend?

The log, dry and crawling with tiny bugs, now lives in our lanai. Our plan is to affix it to the crook of a full-grown crepe myrtle out back. We didn’t trim the tree for years, so it’s got a sturdy, multi-sprouted trunk and a wide canopy overhead, populated by squirrels and cardinals. The tree probably won’t be uprooted in the next hurricane, although you never know. The storms keep getting bigger and windier and rainier and more frequent, as a result of You Know What.

The abandoned woodpecker condo will make a nice home for some other bird family, maybe one that lost their nest to Helene. Maybe not. We’re not bird people, so this is just conjecture.

Still, I’m rooting for that happy ending for bird family no. 2. After natural disasters, it is a normal human response to seek solace in tangible signs of renewal and rebirth. “We shall rebuild.” “We’ll go on.” “We’ll get through this somehow.”

“Somehow.” There’s the crux. It is a word that sustains hope in circumstances where one is planless and powerless. It is not a strategy to protect residents of a state from a climate crisis that has been unfolding for decades. Nor does it address the root cause of that crisis: the burning of fossil fuels.

But “somehow” and crossed fingers are the best that we Floridians have right now. We have no statewide plan for climate-change adaptation and mitigation; cities, communities and individuals have been forced to take up the slack. There is no long-range, statewide plan to rethink coastal housing or to relocate vulnerable communities, as monumental as such a task would be. Instead, development continues at a breakneck pace, both inland and at the water’s edge.

Florida was one of just five states that declined to participate in an Environmental Protection Agency grant program earlier this year, turning down $3 million in federal money to develop a state climate action plan.

The plan is, apparently, to have no plan.

And so, we Floridians are expected to cope with the intensified hurricanes and extreme weather events, like that little fellow who built the bird condo out back, by just winging it.

I can picture the future that our governor and his allies are imagining for us 20, 30, 50 years from now.

Cat 4s and Cat 5s have become nearly season-round phenomena. Some coastal towns have been wiped out or abandoned. South Florida is going underwater, but just slowly enough that the rich can sell off their properties at a profit and relocate. At the 50-year mark, there are no profits to be had. Just run-down high rises on Brickell and Collins and Ocean Drive, mold proliferating on the walls, ground-floor units inundated with calf-deep water stinking of sewage and rotting plants.

And living precariously on the upper floors — at reduced rents or perhaps rent free altogether — the poor, the disabled, the elderly, the addicted, the demented.

Like enterprising birds or hermit crabs, they take possession of once-glittering condos and make do, wandering the beaches and their still-beautiful sunsets, living to see another day, hopefully.

Living testaments to the undeniable, merciless reality of That Which Shall Not Be Named.

Barbara Drake-Vera is an award-winning writer, journalist and climate advocate from Gainesville. Her new book, “Melted Away: A Memoir of Climate Change and Caregiving in Peru” (LSU Press), recounts her life-changing experiences caring for her estranged father with dementia in Lima while racing to report on disappearing glaciers in the Andes. Banner photo: U.S. Airmen assigned to the Florida Air National Guard clear roads in Keaton Beach after the landfall of Hurricane Helene on Sept. 27, 2024. (Staff Sgt. Jacob Hancock/The National Guard, CC BY 2.0, via flickr).

If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu. Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here.