This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. It is republished with permission. Sign up for their newsletter here.

By Amy Green, Inside Climate News

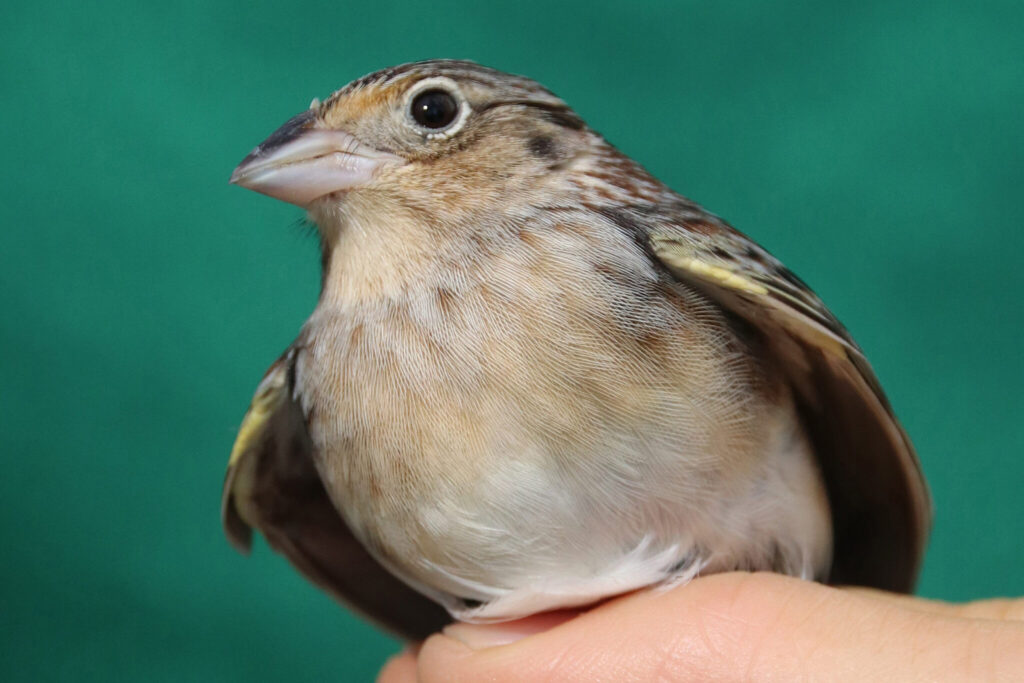

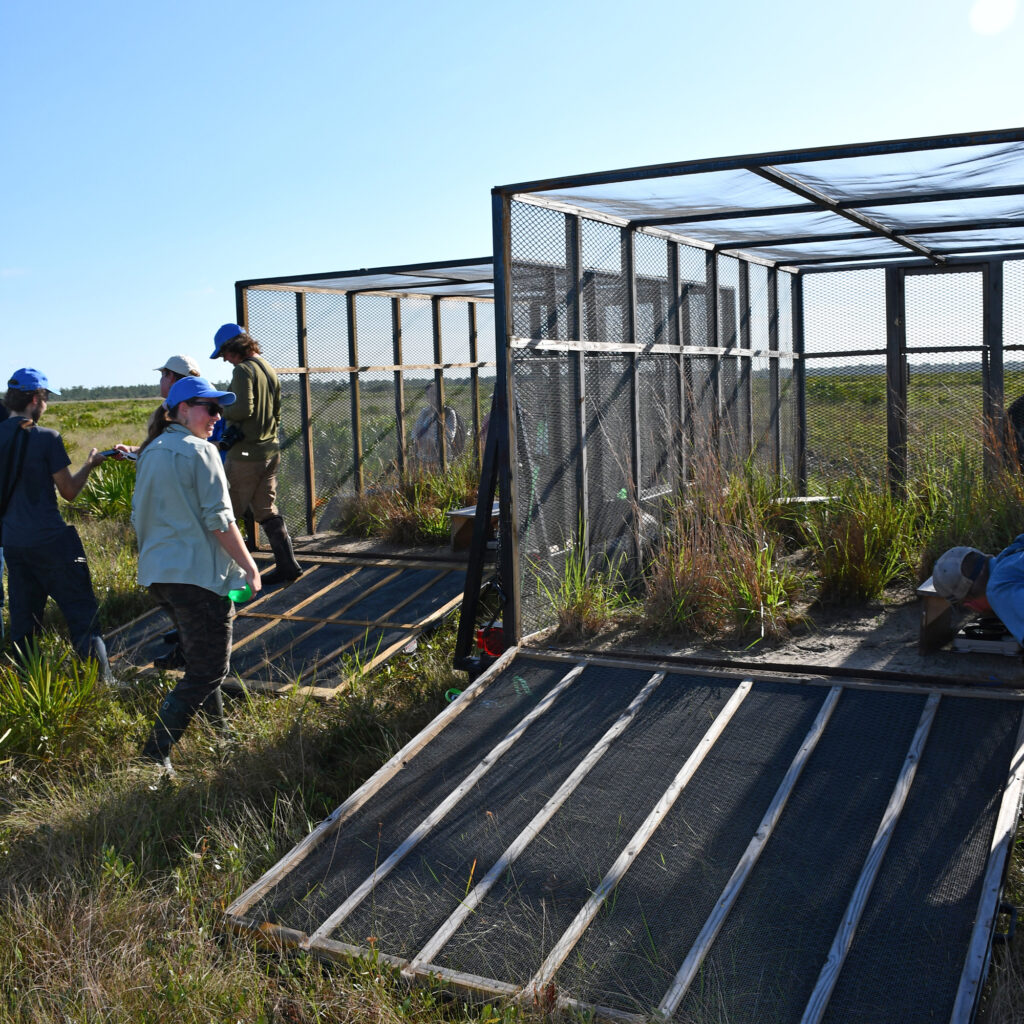

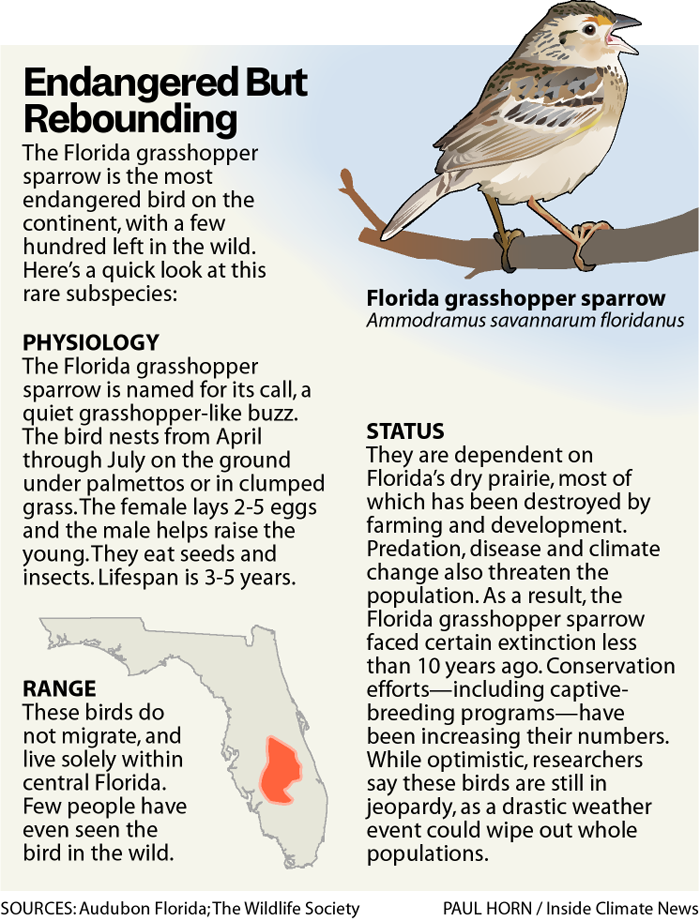

On a recent morning, 10 Florida grasshopper sparrows, tiny brown-speckled birds that are the most endangered on the continent, took their first scampers and flaps on the state’s central prairie.

It happened so fast it was hard to distinguish which of the captive-raised sparrows was the 1,000th released on this expanse of grasslands not far from Walt Disney World, the only place on Earth where the birds are found in their natural habitat.

Dozens of conservationists, gathered some distance away to avoid spooking the skittish sparrows, celebrated the milestone in an unprecedented recovery program that in only a few years has doubled the bird’s wild population, from a mere 80 five years ago to some 200 today.

By the time the land-dwelling sparrows emerged from the two large enclosures and disappeared onto the prairie, the observers couldn’t help but cheer. The moment marked the culmination of years of deliberation, doubt and diligence among those engaged in the bird’s fate, said Paul Gray, science coordinator for the Everglades Restoration Program at Audubon Florida.

“It’s just a lot of hard work by a whole lot of people,” said Gray, who has worked on the Florida grasshopper sparrow for about 30 years and was present for the 1,000th release in July. “I can’t describe how hard it was emotionally for everyone involved in this because every step of the way, we had to do something that nobody had done before.”

The reasons for the Florida grasshopper sparrow’s collapse on the central Florida prairie have confounded conservationists. Two decades ago, more than 1,000 thrived in the wild.

The sparrow nests surreptitiously among the grasses of the prairie, a habitat that itself is unique in the world and once spanned more than a million acres, although today more than 90 percent has been overtaken by the state’s explosive growth and development. The sparrow is among 12 subspecies of grasshopper sparrow that are found throughout North America, Central America and the West Indies.

In addition to habitat loss, the Florida grasshopper sparrow also is vulnerable to predators, disease and climate change. Variations in precipitation and heavy downpours can threaten low-lying nests. In 2016 unprecedented rains prompted conservationists to lift nests, a practice they have continued every year since to prevent nest flooding, said Adrienne Fitzwilliam, the lead Florida grasshopper sparrow research scientist at the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

The subspecies’ population is so small a single weather event or disease could wipe it out. The last bird extinction in the continental U.S. was declared in 1990 for the dusky seaside sparrow, a subspecies of seaside sparrow that vanished from Florida three years earlier.

When conservationists rescued Florida grasshopper sparrows eight years ago from failing or flooded nests, they ended a long debate over whether taking sparrows for captive-breeding might push their wild population closer to the brink.

Other breeding programs involving larger, longer-living birds such as the California condor had been successful, but there was no precedent for a species like the Florida grasshopper sparrow, which weighs no more than five or six pennies and lives a mere three to five years.

“This was important because it was a short-lived grassland bird, and grasslands in general in North America are declining a bit because it’s a place where people develop,” said Robert Aldredge, Florida Air Force partnership coordinator at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “It’s a good place to have farmlands, so grasslands species are not doing the best.”

The sparrows were housed at facilities like White Oak Conservation outside of Jacksonville and the Brevard Zoo on the Space Coast, where their caretakers maintained conditions within their enclosures that closely mimicked those on the prairie. No one knew whether the sparrows would survive, and when they did, no one knew whether they would breed and raise young. Then no one knew whether the young would survive in the wild, and when they did no one knew whether this generation would breed and raise young.

“It was a lot of difficult and very strong feelings, and no one really knew the answer,” Gray said.

The captive-raised sparrows have surpassed expectations in the wild. When conservationists began releasing them in 2019, another step that came after agonizing debate, they hoped at least 15 percent would survive beyond a year and breed with wild sparrows. Initially 20 percent survived and bred, and since then the birds have maintained a 15 percent survival rate, considered a success for a species that never had a high survival rate to begin with.

“It is wonderful news that they have been able to successfully recruit into the population,” Fitzwilliam said. “Their offspring are just like the other sparrows.”

“There was some concern in the beginning of the program, whether the birds would be the same caliber breeders because they were raised in captivity,” she said. “But they have been a huge asset in keeping the population basically from winking out.”

The next step will be getting enough captive-raised birds onto the prairie so that the population can become self-sustaining, Gray said.

“How do we get enough birds out there, and will it be self-sustaining?” he asked. “That is what keeps me awake.”

Fitzwilliam said that while the Florida grasshopper sparrow still faces many threats, the population has stabilized to the point where conservationists can turn their attention toward other issues, such as how the landscape itself can be improved, through fire for instance.

“There were a lot of exercises where we imagined the very worst case scenario,” she said. “What we have achieved is the best case scenario. The birds are able to settle. They are able to breed. They are able to contribute to the population. So that piece of the puzzle, it’s very exciting that it’s working out well.”

Banner photo: Conservation history was made in 2016 when the first captive-bred Florida grasshopper sparrow chicks hatched at the Rare Species Conservatory Foundation (RSCF) in Loxahatchee, Fla. (Photo credit: RSCF/www.rarespecies.org, CC BY 2.0, via flickr).

Amy Green covers the environment and climate change from Orlando, Florida. She is a mid-career journalist and author whose extensive reporting on the Everglades is featured in the book “Moving Water,” published by Johns Hopkins University Press, and podcast “Drained,” available wherever you get your podcasts. Amy’s work has been recognized with many awards, including a prestigious Edward R. Murrow Award and Public Media Journalists Association award.

This story was produced in partnership with the Florida Climate Reporting Network, a multi-newsroom initiative founded by the Miami Herald, the South Florida Sun Sentinel, The Palm Beach Post, the Orlando Sentinel, WLRN Public Media and the Tampa Bay Times.

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.