By Paris Santiago, FAU Center for Environmental Studies

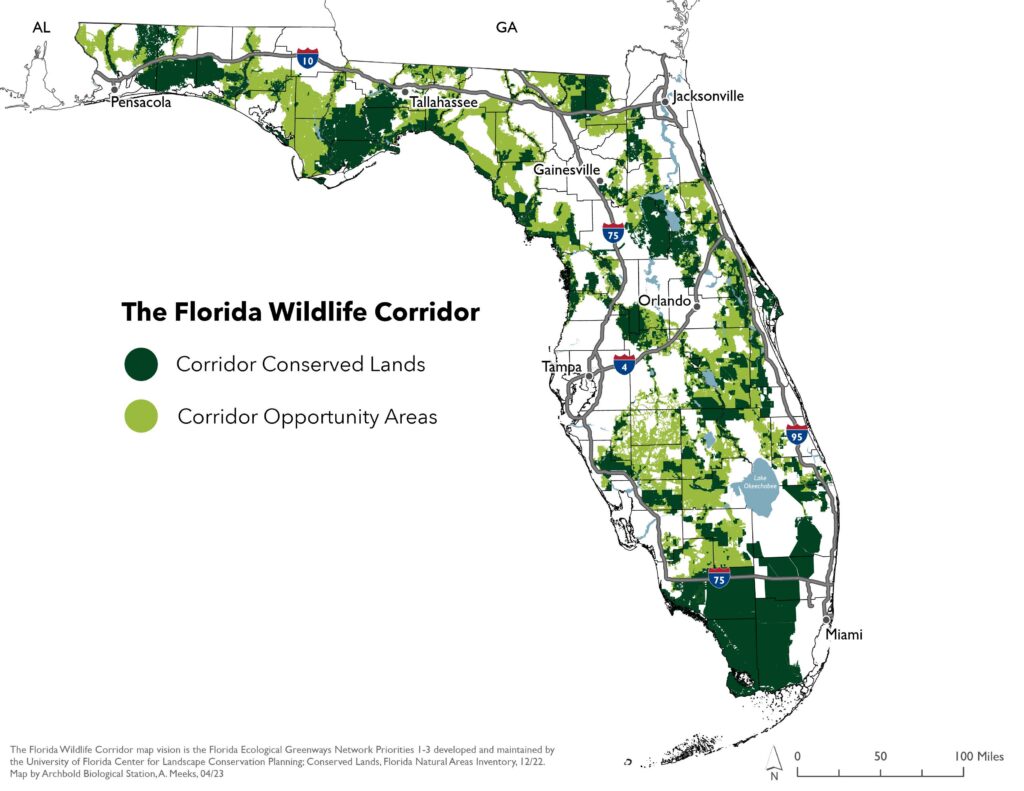

The following Q&A was conducted with Charles “Buck” MacLaughlin, operations officer at Avon Park Air Force Range. The bombing and gunnery range spans 106,000 acres in Polk and Highlands counties. The military training facility includes land in the Florida Wildlife Corridor, a statewide network of interconnected lands that provide passage for imperiled wildlife while mitigating climate and population pressures. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell me about your role as the director of range operations at Avon Park Air Force Range.

My primary job is range operations officer managing the operation of an Air Force primary training range. … In the past, I was the commander of the range during my last active-duty assignment and retired in 2012. I spent a year working for the Central Florida Regional Planning Council before getting an opportunity to come back as a general service employee for the Air Force in this current capacity.

It was at that time that I had the opportunity to start working with the community through a process called a joint land-use study, a Department of Defense (DOD) funded initiative that works with the local community to look at comprehensive plans, development plans, and also to look at the current and anticipated future mission of the installation of a training range. It also serves to come up with a set of recommendations for compatible development and compatible policies going forward, where the Air Force is not being encroached upon, and the community is not subject to too much of the effect of military training such as noise, vibration, etc. It’s really an effort to work and plan together to help the range ensure that we’re continuing to be good neighbors.

Part of that role as the commander, particularly through that joint land use study for the DOD, is the Readiness and Environmental Protection Integration (REPI) program. The REPI program is DOD funding that can go to conservation partners for the voluntary acquisition of conservation easements outside the fence line within the community. We work with willing landowners if it is their goal to sell an easement or development rights to the Air Force so that we can ensure that compatible land use stays in place in perpetuity.

Given our very beneficial location on the Lake Wales Ridge, a unique area of biodiversity within the state of Florida and across the world (and now subsequently with our placement within the Florida Wildlife Corridor), those easements are most commonly done in the form of working with conservation partners. This includes the Nature Conservancy, Conservation Florida and state agencies like Rural and Family Lands Protection Program or Florida Forever, which really creates a partnership opportunity for some win-win benefits. …

You were a panelist at the FAU Frontiers in Science Lecture Series where mentioned a synergy between the Department of Defense’s mission and the natural environment. Can you elaborate on that intersection?

I think it’s safe to say that most people, when they think conservation and the natural environment, do not then think of the DOD and military training and activities. But there is surprising synergy between the two.

One of the best ways of describing it is that when military forces train and practice what they need to do in combat, they need that freedom of maneuver to be able to really operate as if they were operating under combat conditions, or at least to the best that we can simulate that in peacetime. That freedom of maneuver is exactly the same kind of freedom of maneuver that wildlife depends on, particularly some of Florida’s iconic species like the Florida panther or black bear. Species don’t operate well in a closed, confined space, and neither does the military.

That lays the framework, but, specific to Avon Park range, some of the training that we accomplish and host are dangerous activities. … As such, we have to ensure that we keep not only range staff, but more importantly the public, (are) safely buffered from those hazardous activities. Those “buffer zones” (or management areas, as we call them) are a perfect opportunity because we don’t want people or development or things that could be harmed by hazardous activities in the area. These are perfect areas to really keep a natural habitat state and provide conservation property for all species, both plants and animals.

It’s that opportunity of ensuring buffer areas for safety as well as compatible land uses outside our fence line that make us a great partner for opportunities such as the Florida Wildlife Corridor. We have those same goals to protect those natural areas, ranches and open spaces for a compatible land use and to enhance our own internal conservation efforts. That matches with conservation agencies and the Florida Wildlife Corridor’s efforts to protect open space and natural spaces. It may be a partnership that is not intuitively obvious when you first think about it.

Are you able to talk about the process of prescribed burns and their role in wildlife conservation efforts?

At the Air Force range we have, I believe, the Air Force’s second-largest prescribed fire program. Because of that program, I’ve had the opportunity to learn just how important fire is for the Florida ecosystem and how many plant and animal species are really dependent on fire.

For me, that was not something that seemed obvious at first glance. When you think Florida, you think swamps, ocean and a lot of rain, so fire doesn’t seem to fit with that perception. Throughout the area that surrounds the range, getting prescribed fire on the on the ground is so important for the quality of the habitat and of those natural areas, as well as for resiliency for the range and the community.

As we experience drier and hotter conditions, the potential for catastrophic and damaging wildfire grows. Our No. 1 protection against those catastrophic, out-of-control wildfires is applying control through prescribed fire on the landscape. We’ve been fortunate to be part of a number of initiatives to get additional capability within the community, and within the Sentinel landscape partnership or the conservation partners in the area, to be able to put more fire on the ground.

From a range perspective, that is absolutely a key aspect of our natural resource management. We intentionally burn about one-third of the range every year – about at a pace that nature did before mankind really kind of got established and put in the impediments to fire. The end result is that if you’re able to burn at that rate, the environment really benefits from those activities in that pace.

How overall will the wildlife corridor impact wildlife conservation efforts in Florida?

Starting out with the Wildlife Corridor Act, (there was) 100% bipartisan agreement for the passage of the act. How many times does that happen in today’s political environment? I think the real benefit of the Florida Wildlife Corridor is it has the focus on not just pockets of conservation, but really that connectivity and as the name implies.

From a range perspective, we’ve been looking at the fact that if safety buffer areas that I mentioned earlier become the last viable habitat for a certain species, particularly if it’s threatened and endangered, there comes a lot of restrictions with how we can use that area. Those internal conservation efforts are not nearly as effective if they’re a small island of biodiversity. That’s just the focus of the wildlife corridor: that we’re not going to meet our end goals by having little tiny separate pockets of natural and conserved lands. It’s really that corridor and connectivity that is an important part to save and to protect.

I don’t think there’s a more pertinent time for an effort like the Florida Wildlife Corridor than today with the intense pressure that we’re facing in terms of population growth. There’s over a thousand people per day moving to Florida on average. You factor that over an entire year, that’s another Orlando every year. We need that big-vision initiative like the Florida Wildlife Corridor that really helps us focus in on the key areas that really need to be protected … those “opportunity areas” as the corridor effort describes them, and how can we bring a coalition of partners together to try to protect those, not only for nature but for Florida’s economy as well.

The wildlife corridor also really fits in well with the Sentinel landscapes partnership, a nationwide program that designated Avon Park to be recognized as a landscape where conservation and ecology come together with working lands with a military component. From a federal perspective, Department of Agriculture, Department of Interior and Department of Defense all have those objectives within that landscape. It really is a unique opportunity that we have that I think fits very well with the idea of the Florida Wildlife Corridor.

Overall, how do you see the wildlife corridor’s role in Florida’s future climate resilience?

I definitely think they’re going to be a leader. To my knowledge, there is not another state in the nation that has something like the Florida Wildlife Corridor. There’s initiatives and there’s other wildlife corridors, but the amount of funding that is coming from the state government for that initiative is unique and rather unprecedented. Florida, in my viewpoint, is leading the nation in in terms of what can be done.

The other thing that I think (about) the wildlife corridor that is really going to impact those efforts and climate resiliency is that they’re not just (using) an approach that says, “No development, we have to conserve and protect all this land.” While that in many ways is a very admirable goal, the reality is that you can’t print enough money to buy up and conserve every bit of property that we want to.

When a thousand people per day are coming to Florida, there is going to have to be development. So, we can help inform developers where to develop and where to leave alone to stay in conservation. Being able to advise and perhaps inform developers on where to develop is part of it. And then additionally, they’re looking at the developments themselves and how we can develop in a way that is better for wildlife and allows connectivity throughout a development. So they’re really looking at the efforts in that regard.

They’re also looking at the economic viability of conservation and where priorities are, as well as different ways of accomplishing some of the goals such as payment for ecological services or environmental services. So it’s less than an outright acquisition of a conservation property, but maybe we can work with a landowner to pay them to take care of the land, which ideally opens up a lot of avenues.

I’m not aware of another effort in any other state that has the potential that the Florida Wildlife Corridor does.

Banner image: An HH-60 Pave Hawk helicopter at Avon Park Air Force Range with a prescribed fire in the background. (Image courtesy of Avon Air Force Range)

This Q&A was conducted by Paris Santiago, a graduate research assistant at Florida Atlantic University who is pursuing a master’s degree in the environmental science program. She has worked as a research assistant for FAU’s Center for Environmental Studies since 2022. The center manages The Invading Sea.

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.