By Kristan Reynolds, The Invading Sea

ORLANDO, Fla. – On a hot July day, downtown Orlando’s urban environment can feel like an oven. For 19-year-old Sa’Kearia Johnson and her 6-year-old brother, their 30-minute walk to Lake Eola Park, located in the heart of downtown, is anything but a stroll; It’s a difficult trek through an urban heat island.

“It’s very hot; It’s stifling hot,” Johnson said, sitting on a park bench gripping a plastic water bottle as her younger brother braved the playground obstacles. Johnson says that her walk through the built downtown environment “feels like you’re barely making it to your destination,” but the park’s shade and breeze give her a chance to temporarily escape the hot pavement.

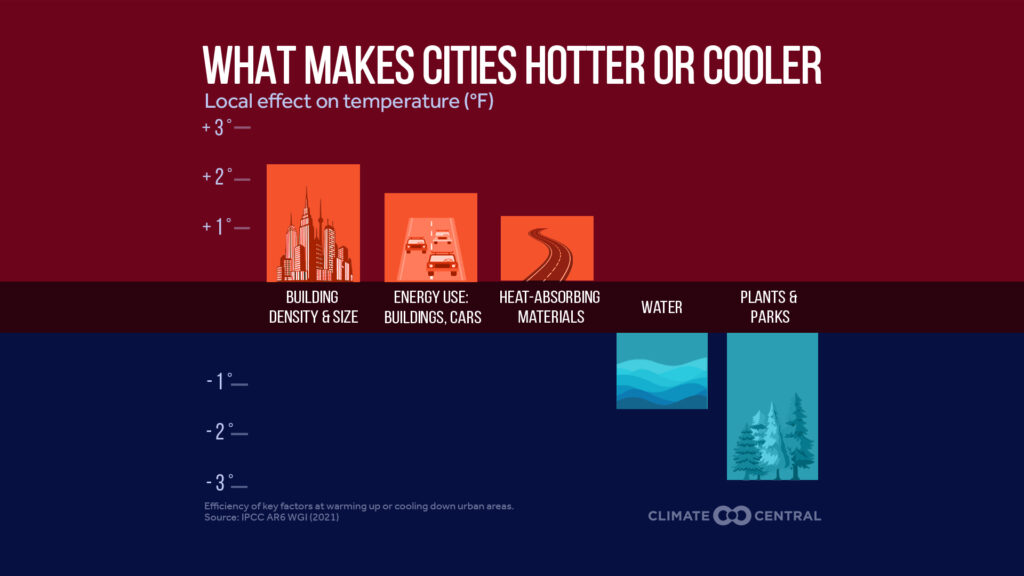

While temperatures are already rising globally due to human-caused climate change, millions of people in U.S. cities are facing additional temperature increases due to the urban heat island effect, according to a new study by Climate Central. The urban heat island effect amplifies temperatures due to the built environment absorbing more heat than forests and other natural landscapes.

Climate Central’s analysis of 65 major U.S. cities found that 34 million people are living in areas where urban heat islands increase temperatures by at least 8 degrees Fahrenheit.

“Urban heat islands are an area of elevated temperature that is a result of the built environment — so buildings, streets, anything paved and the population density and the heat we generate as people,” said Jennifer Brady, Climate Central’s senior data analyst and research manager. “These are a concern because the temperatures are going up everywhere because of climate change, and … in the cities, you have this additional heat added on top of those already rising temperatures.”

The study identified three Florida cities among those where the highest percentage of the population experiences at least 8 degrees higher temperatures due to the urban heat island effect: Fort Myers (96% of the population), West Palm Beach (94%) and Tampa (87%).

Urban heat islands can pose various health risks and economic issues, but the study identified various short and long-term solutions to mitigate the effects. Creating additional green space (vegetated areas within urban environments) is one effective method, as plants cool the air and can help reduce peak summer temperatures by 2 degrees to 9 degrees in urban areas, according to the report.

“Heat is the biggest weather killer, which we often overlook because it doesn’t have the drama of a hurricane or a tornado, but it’s very dangerous,” Brady said.

According to the report, urban heat islands can put residents and visitors alike at increased risk for heat-related illnesses, such as heat exhaustion. Additionally, city residents can face economic hardships like dramatically increasing cooling costs.

“Urban heat islands keep the city warmer at night too,” Brady said. “So maybe you think, ‘Oh, I can turn my air conditioner off at night and it’ll be a little cooler.’ That’s not as true anymore because the temperatures are going up at night overall.”

Out of the 65 studied cities, six cities had more than 1 million residents exposed to urban heat island indexes of 8 degrees or more. This means that if the normal temperature was 90 degrees Fahrenheit, the built environment would elevate those temperatures to 98 degrees or higher — exposing massive populations to potential danger and higher energy costs that may not be affordable to all, says Brady.

“It’s millions of people — millions and millions of people,” Brady said about those impacted by the urban heat island effect. “It could be hundreds of thousands of people in just a single city, so it’s very significant.”

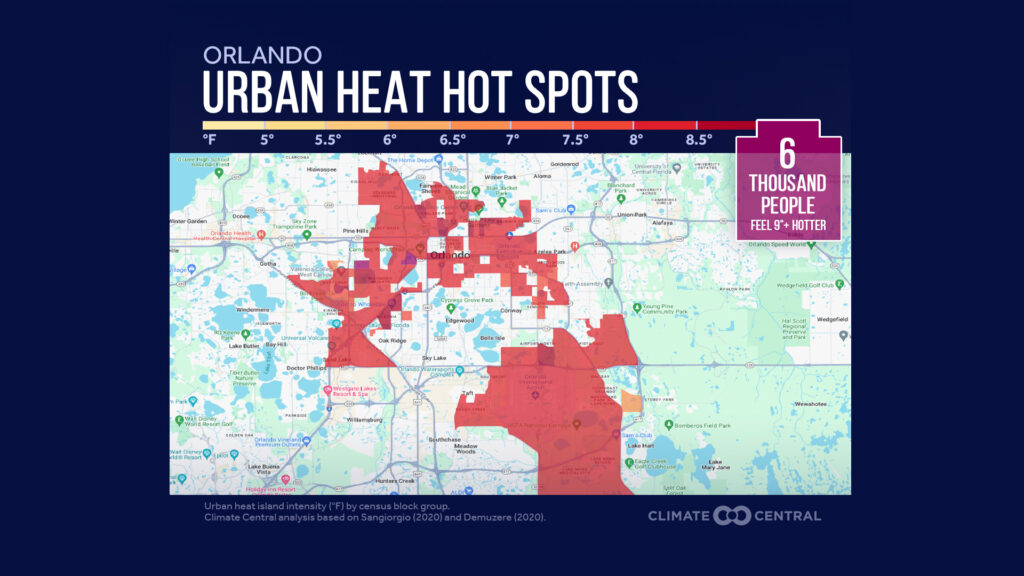

Climate Central’s Urban Heat Island Map allows users to view graphics showing shows where urban heat is most intense in the studied cities. Brady hopes the information helps people “get a sense of where the hot spots are in your city and what the problem is, and then also just start the discussion about: What are the materials that we live with doing to our environment?”

While the urban heat island effect is present in numerous U.S. cities, the report offers various long and short-term solutions that can reduce the urban heat island effect.

These solutions include planting trees for shade and heat-reduction and cool pavements (which are made with paving materials that stay cooler than traditional pavement) that reduce surface temperatures. Additionally, green roofs (rooftop gardens) and cool roofs (stay cooler than traditional roofs) can reduce energy costs while mitigating the urban heat island effect.

“We’re seeing people implementing solutions at the community level, planting gardens or trees in areas where you can have some shade benefit,” Brady said. “But you’re also seeing large engineering solutions like painting roadways more reflective colors, or painting rooftops — which are much more expensive and are going to require the city or the state to do that.”

The study found Orlando fared better than several Florida cities, but still had nearly 194,000 residents – or 63% of its population – living in areas where urban heat islands increase temperatures by at least 8 degrees. Nearly 6,000 residents live in areas of Orlando where urban heat islands increase temperatures by at least 9 degrees, according to the study.

The city of Orlando is collaborating with Orange County’s environmental office to reduce the urban heat island effect. The county’s comprehensive land use plan includes “specific references to helping reduce the urban heat island effect,” said Carrie Black, Orange County’s chief sustainability and resilience officer.

The county is currently working on updating the plan, known as Vision 2050, which includes goals of increasing the existing tree canopy (38.9%) in unincorporated Orange County for additional shade and heat reduction. The plan also aims to ensure wide access to public and green spaces — from small “pocket parks” to larger county parks.

Black also identifies transportation as intensifying the urban heat island effect. The county funds projects to increase public transit and sidewalk connectivity through its Accelerated Transportation Safety Program and recently launched its micro-mobility program that provides electric scooters and bikes.

“You ride the bus, and it drops you off a couple blocks from your final destination … Jump on this e-scooter, and you’re there in two minutes,” said Black about the micro-mobility program. “So that way people won’t have to get in their car to drive that half mile down to their next destination within that corridor.”

Black hopes that Orange County can lead by example when it comes to combating the urban heat island effect and climate change.

For residents such as Johnson, the heat requires them to be prepared when navigating Orlando.

“Everybody should have a water bottle and then some,” Johnson said. “And if you’re too hot, you need to go sit somewhere in the AC because it’s too hot to be outside with no water and no air.”

Kristan Reynolds is a Florida Atlantic University senior majoring in multimedia journalism and minoring in communication studies who is reporting for The Invading Sea during the summer 2024 semester. Banner photo: Sunset over the Orlando skyline and Lake Eola Park (iStock image).

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu. To learn more about the urban heat island effect, watch the video below.

Thank you so much, many folks need to be warned about this danger. Floridians are not use to this kind of heat and one gallon of water is what is needed daily to truly hydrate your body.

Drink more water and hopefully it’s clean. Sign the petition for a fundamental right to clean water in our state.

FloridaRighttoCleanWater.org

Thank you.