By the Tampa Bay Times Editorial Board

Let’s all lean in so we can ask this in a whisper. No need to tempt fate, after all. Here it goes: Have you noticed how Florida’s hurricane season has been fairly quiet so far?

Yes, as of Wednesday, five storms had formed in the Atlantic Basin, which includes the Gulf of Mexico, with one strengthening into a weak hurricane. But none threatened the Sunshine State. The news couldn’t be better, especially in the Fort Myers area still digging out from devastating Hurricane Ian. It’s too soon to know for sure, but we likely have El Niño to thank. Present this year, the climate phenomenon helps suppress hurricane activity.

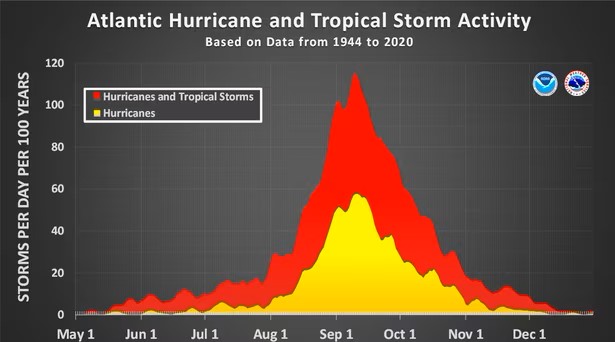

But … and you knew there would be a but … we are about to hit hurricane prime time, the eight weeks of the year when storm activity peaks. Hurricane season officially lasts from June to the end of November, but much of the action gets concentrated from about mid-August to mid-October.

Just look at the chart accompanying this editorial. The peak on the graph indicates that it’s a very safe bet that at least one tropical storm will be in the Atlantic Basin around Sept. 10 every year. And while El Niño might be helping us this year, sea surface temperatures are worryingly high. Storms feed off of warm water. Will the high water temperatures overwhelm the protections provided by El Niño? It’s hard to tell, but we’re rooting for El Niño.

Colorado State University’s Tropical Weather and Climate Research team is predicting 18 named storms, including the five already. They expect nine of the storms to strengthen into hurricanes, with four becoming major hurricanes, packing maximum sustained winds speeds of at least 111 mph. AccuWeather forecasters recently updated their forecast from 13 to 17 named storms — up from 11 to 15 — and added that the next few weeks could be “very active.” It’s all a good reminder to have a solid hurricane plan in order. It’s also a good time to brush up on our hurricane facts and figures.

Since the early 1990s, there’s been a steady increase in the number of hurricanes in the Atlantic Basin. The 20-year average is higher than anytime since at least 1880. Is climate change to blame? Not so fast.

First, improved technology since about 2000 has allowed researchers to identify more short-lived storms than in the past, potentially padding the total. Plus the overall research hasn’t linked climate change to the formation of more hurricanes, called typhoons and cyclones in some other parts of the world. In fact, a drop in the number of hurricanes in the Pacific region more than offsets the increase in the Atlantic. That’s right: Global hurricane activity has waned significantly since 1990, despite a warming climate, according to research published last year. Phil Klotzbach, who co-authored the report, attributed the decline to a general trend toward La Niña conditions, even though we are in El Niño at the moment.

“While La Niña increases Atlantic hurricane activity, it tends to decrease Pacific activity,” said Klotzbach, part of Colorado State’s climate and weather team. “Since the Pacific generates much more activity than the Atlantic climatologically, La Niña tends to reduce global storm activity.”

The good news is that the number of hurricanes that make landfall in the continental U.S. remains fairly steady. Same for strikes from major hurricanes. That doesn’t mean one won’t hit us, it just means the likelihood isn’t much different than it has been at most times since the late 1800s. In 1905, seven hurricanes struck, the most of any year since at least 1890, followed by the six strikes in 2004. Historically, fewer than two hurricanes make landfall in the continental United States in a year. A major hurricane hits about every two years.

Of course, hurricanes cause more damage now than 120 years ago. Not because the storms are more powerful. The reason has more to do with how and where we have built. Hurricanes used to slam into Florida but do little damage. There were fewer things around to break. As an example, compare last year’s Hurricane Ian to the 1926 Great Miami hurricane, both Category 4 storms when they struck. Ian caused $112 billion in damage, making it the state’s costliest hurricane ever and the third-costliest in U.S. history.

But what if the Great Miami hurricane followed the same path and packed the same punch as it did in 1926, but instead it hit Miami today? Total estimated damage: $267 billion, according to an analysis published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Sustainability and updated annually. Accounting for today’s level of development, the Great Miami hurricane would be the costliest storm in history if it hit today, followed by the Galveston hurricane in 1900, Hurricane Katrina in 2005, another Galveston storm in 1915 and Hurricane Andrew in 1992.

Our elected officials need to think more deeply about the tradeoffs of continuing to build in the state’s most vulnerable areas. That’s not an argument to stop all construction, but is it any wonder that we have a property insurance crisis when so many homes and other properties are directly in harm’s way? Tough choices will have to be made, and in some cases, that will mean pulling back from the most vulnerable areas. Our officials should also encourage more programs like My Safe Florida Home to harden existing homes.

Looking into the future, research indicates that storms could move slower, spend more time over populated areas, and pack more rainfall, much like Hurricane Harvey, which dropped more than 50 inches of rain on one part of the greater Houston area in 2017. Rising sea levels could push flooding farther inland. Also, some research shows that the number of storms that rapidly intensify — that is, gain more than 60 mph in wind speeds in 24 hours — has increased significantly. The rapid strengthening can wreak havoc on communicating accurate forecasts in real time and coordinating evacuation plans. Again, all the more reason to be personally prepared.

Bottom line: Hurricanes are a way of life in Florida, and the next few weeks will almost certainly test some of us again. Be ready, be kind to your neighbors, and fingers crossed that El Niño keeps the storms away.

Editorials are the institutional voice of the Tampa Bay Times. The members of the Editorial Board are Editor of Editorials Graham Brink, Sherri Day, Sebastian Dortch, John Hill, Jim Verhulst and Chairman and CEO Conan Gallaty.

This opinion piece was originally published by the Tampa Bay Times, which is a media partner of The Invading Sea. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu. Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here.