By Eunyoung Choi, University of Southern California

What if extreme heat not only leaves you feeling exhausted but actually makes you age faster?

Scientists already know that extreme heat increases the risk of heat stroke, cardiovascular disease, kidney dysfunction and even death. I see these effects often in my work as a researcher studying how environmental stressors influence the aging process. But until now, little research has explored how heat affects biological aging: the gradual deterioration of cells and tissues that increases the risk of age-related diseases.

New research my team and I published in the journal Science Advances suggests that long-term exposure to extreme heat may speed up biological aging at the molecular level, raising concerns about the long-term health risks posed by a warming climate.

Extreme heat’s hidden toll on the body

My colleagues and I examined blood samples from over 3,600 older adults across the United States. We measured their biological age using epigenetic clocks, which capture DNA modification patterns – methylation – that change with age.

DNA methylation refers to chemical modifications to DNA that act like switches to turn genes on and off. Environmental factors can influence these switches and change how genes function, affecting aging and disease risk over time. Measuring these changes through epigenetic clocks can strongly predict age-related disease risk and lifespan.

Research in animal models has shown that extreme heat can trigger what’s known as a maladaptive epigenetic memory, or lasting changes in DNA methylation patterns. Studies indicate that a single episode of extreme heat stress can cause long-term shifts in DNA methylation across different tissue types in mice. To test the effects of heat stress on people, we linked epigenetic clock data to climate records to assess whether people living in hotter environments exhibited faster biological aging.

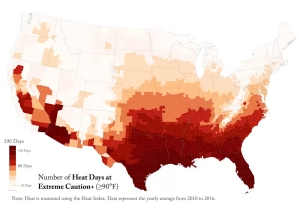

We found that older adults residing in areas with frequent very hot days showed significantly faster epigenetic aging compared with those living in cooler regions. For example, participants living in locations with at least 140 extreme heat days per year – classified as days when the heat index exceeded 90 degrees Fahrenheit (32.33 degrees Celcius) – experienced up to 14 months of additional biological aging compared with those in areas with fewer than 10 such days annually.

This link between biological age and extreme heat remained even after accounting for a wide range of individual and community factors such as physical activity levels and socioeconomic status. This means that even among people with similar lifestyles, those living in hotter environments may still be aging faster at the biological level.

Even more surprising was the magnitude of the effect – extreme heat has a comparable impact on speeding up aging as smoking and heavy alcohol consumption. This suggests that heat exposure may be silently accelerating aging, at a level on par with other major known environmental and lifestyle stressors.

Long-term public health consequences

While our study sheds light on the connection between heat and biological aging, many unanswered questions remain. It’s important to clarify that our findings don’t mean every additional year in extreme heat translates directly to 14 extra months of biological aging. Instead, our research reflects population-level differences between groups based on their local heat exposure. In other words, we took a snapshot of whole populations at a moment in time; it wasn’t designed to look at effects on individual people.

Our study also doesn’t fully capture all the ways people might protect themselves from extreme heat. Factors such as access to air conditioning, time spent outdoors and occupational exposure all play a role in shaping personal heat exposure and its effects. Some individuals may be more resilient, while others may face greater risks due to preexisting health conditions or socioeconomic barriers. This is an area where more research is needed.

What is clear, however, is that extreme heat is more than just an immediate health hazard – it may be silently accelerating the aging process, with long-term consequences for public health.

Older adults are especially vulnerable because aging reduces the body’s ability to regulate temperature effectively. Many older individuals also take medications such as beta-blockers and diuretics that can impair their heat tolerance, making it even harder for their bodies to cope with high temperatures. So even moderately hot days, such as those reaching 80 degrees Fahrenheit (26.67 degrees Celcius), can pose health risks for older adults.

As the U.S. population rapidly ages and climate change intensifies heat waves worldwide, I believe simply telling people to move to cooler regions isn’t realistic. Developing age-appropriate solutions that allow older adults to safely remain in their communities and protect the most vulnerable populations could help address the hidden yet significant effects of extreme heat.![]()

Eunyoung Choi is a postdoctoral associate in gerontology at the University of Southern California.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Banner photo: A woman puts on sunglasses on a sunny day (iStock image).

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. To support The Invading Sea, click here to make a donation. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.