This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

By Amy Green, Inside Climate News

When the federal and state governments sought during the First and Second Seminole wars to forcibly remove Native Americans from Florida, the Indigenous peoples found sanctuary among the tree islands scattered within the watery wilderness of the Everglades.

Now a new report on the progress of the $21 billion effort to restore the vast watershed acknowledges a lack of meaningful engagement with the Miccosukee and Seminole tribes, who consider the soaring cypress swamps and sweeping sawgrass prairies of the river of grass that saved them from annihilation more than 100 years ago to be sacred.

The report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine also calls for a strategy for understanding how climate change will affect the massive effort, one of the most ambitious attempts at ecological restoration in human history.

“The tribe has been involved in Everglades restoration since the beginning of Everglades restoration,” said Edward Ornstein, deputy general counsel for the Miccosukee Tribe. “The tribe appreciates the National Academies beginning to recognize and incorporate the value of Indigenous knowledge, which can provide Everglades restoration practitioners with a broader and more accurate understanding of the ecosystem they are seeking to restore.”

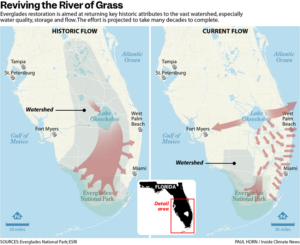

The Everglades are Florida’s most important freshwater resource. The watershed begins in central Florida with the headwaters of the Kissimmee River and encompasses Lake Okeechobee, sawgrass marshes to the south and Florida Bay, at the peninsula’s southernmost tip.

Various efforts during the past century to drain the Everglades made modern Florida possible and left the river of grass drastically altered. Restoration involves a series of landscape-scale projects, each massive on its own. The National Academies, a private nonprofit organization, has provided biennial reports on the effort’s progress since 2004, based on a congressional mandate.

The latest report, released in October, calls for a consistent partnership between the federal and state agencies involved in the endeavor and Native tribes. Indigenous knowledge predates western scientific studies, providing an opportunity to better understand historical ecological conditions and how they compare with today’s circumstances, the report said.

“It’s sort of difficult to conceptualize Everglades restoration when you don’t know what you’re restoring the lands to be,” Ornstein said.

This is the first time the National Academies have emphasized the tribes’ importance in Everglades restoration and reflects a growing awareness within the community of the tribes’ value, he said. The Miccosukee have long acted as environmental stewards in Florida, notably helping to steer stringent quality standards for their waterways. Today most of the tribe’s 600 members live on tribal lands within Everglades National Park.

An internal review process the Miccosukee recently developed based on federal requirements for data quality represents a potential model as restoration programs nationwide consider how to meaningfully incorporate Indigenous knowledge, according to the report. The Biden administration released guidance in 2022 for including Indigenous knowledge in federal research, policy and decision-making.

“The onus is now upon the agencies to meet the Tribes ‘where they are’ and develop protocols that effectively consider and apply Indigenous Knowledge even when it does not conform to western scientific norms and presentation,” the National Academies report said.

The report also recommends that Everglades professionals undergo training to improve relations with the tribes. The report acknowledges that a lack of engagement historically heightens the need to build trusting relationships. Gary Bitner, spokesman for the Seminole Tribe of Florida, said the tribes are actively working with the government agencies toward preserving the watershed that is responsible for the drinking water of some 12 million Floridians.

“Close cooperation is already happening,” he said.

“The value of our natural world is woven into the culture of the Miccosukee Tribe and the Seminole Tribe in such a meaningful way, and the rest of the Everglades restoration community can learn from it and embrace that approach more,” said Eve Samples, executive director of Friends of the Everglades, a nonprofit advocacy group that has partnered with the Miccosukee in litigation aimed at improving water quality in the river of grass.

“I think it can help us from veering into over-engineered solutions that we’ve found ourselves in in the Everglades over the decades. It’s about living in harmony with the Everglades, not trying to over-engineer the Everglades.”

The report also acknowledges the challenge of factoring climate change into Everglades restoration. Steve Davis, chief science officer at the Everglades Foundation, a nonprofit advocacy group, said one challenge is that the models used to plan projects are based on historical data, even as the warming climate is leading to hotter temperatures, rising seas and changes in precipitation. Incorporating future projections in the planning process is complicated because already the effort is extraordinarily complex, he said.

“It’s a big process, obviously,” he said. “You’ve got state, federal, local, tribal entities all involved with this process and providing input.”

The National Academies report suggests developing a series of projected scenarios, based on variables such as hotter temperatures and rising seas, to layer with the models. The scenarios would help planners identify vulnerabilities that could affect the wildlife and habitats the projects are meant to preserve.

The Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan, now in its 24th year, is the largest of the restoration efforts underway in the fragile watershed. The effort has proceeded in recent years at a dramatic pace, thanks to record levels of federal and state funding. The report said projects are complete or under construction in nearly every region of the watershed.

Investments in invasive species control have contributed to a 75 percent reduction in the area dominated by melaleuca, an especially thirsty tree introduced to the river of grass near the turn of the 20th century to help drain it.

Meanwhile, water quality and phosphorus concentrations continue to improve, although the report points out that whether standards are met will depend on the performance of stormwater treatment areas, vast engineered wetlands that still are under construction. Samples raised a concern about President-elect Donald Trump, who during his last presidency rolled back more than 100 regulations meant to protect air, water, endangered species and human health.

“Having funds flowing, having the money flowing to Everglades restoration is not enough,” she said. “We have to pair these big earth-moving restoration projects with a meaningful regulatory system that is going to ensure that we have the right water quality and that we’re properly regulating polluters so that the system can thrive and these projects can work.

“So there’s been record amounts of federal and state dollars flowing to restoration in recent years, but money alone is not enough to save the Everglades. We also have to have a strong regulatory framework, and that is a very heavy question at this moment.”

Amy Green covers the environment and climate change from Orlando. She is a mid-career journalist and author whose extensive reporting on the Everglades is featured in the book “Moving Water,” published by Johns Hopkins University Press, and podcast “Drained,” available wherever you get your podcasts. Amy’s work has been recognized with many awards, including a prestigious Edward R. Murrow Award and Public Media Journalists Association award. Banner photo: Everglades National Park (Daniel Kraft, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons).

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. To support The Invading Sea, click here to make a donation. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.