By Mallory M. O’Connor

Writing about the climate is nothing new. Generations of writers have called upon descriptions of the climate to ground their stories in the real world and to add an emotionally charged backdrop for the actions of their characters.

In the 19th century, poets and novelists relied on florid descriptions of the climate to heighten the drama of their tales – like the phrase, “It was a dark and stormy night.” Twentieth century modernists dismissed such descriptions as “the archetypal example of a florid, melodramatic style of fiction writing.”

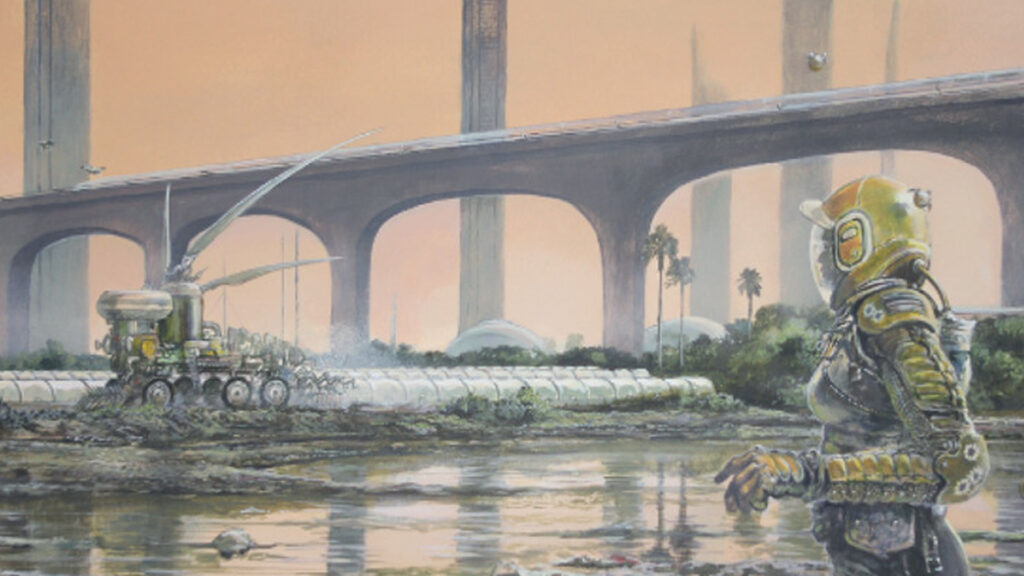

But as we move into an increasingly uncertain future, writers are attempting to document the issues and propose possibilities for coping with present and future climate changes initiated and accelerated by human activities. The result is a new literary genre dubbed “cli-fi,” stories about the results of climate change and its impact on groups and individuals.

I first heard about “cli-fi” from journalist Dan Bloom, who is credited with inventing the term. Bloom is a self-described “climate activist of the literary kind” who now makes his home In Taiwan. In a recent interview, Bloom said, “My most important work so far has been to help promote a new literary term, ‘cli-fi” and then to boost its popularity in the media as a headline term and an actual literary genre different from sci-fi.”

Generally speculative in nature but inspired by climate science, works of climate fiction may take place in the world as we know it, in the near future or in fictional worlds experiencing climate change. Some of the typical elements of cli-fi writing include a crisis that results in a fearful and anxious mood and a plot that centers on the emotions of the characters.

The genre, as a whole, focuses on the potential consequences of climate change and how the characters cope (or fail to cope) with the outcomes. Psychologists assert that cli-fi stories help build “emotional resilience” and help individuals “connect emotionally” with the climate crisis.

The genre’s growing presence in college curriculums, as well as its ability to bridge science with the humanities and activism, is making environmental issues more accessible to young readers — proving that literature may be a surprisingly valuable tool in efforts to reduce global warming.

In “The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable,” Amitav Ghosh questioned why so few writers – himself included – were tackling the world’s most pressing issue in their fiction. Yet it has been pointed out that “climate” has long been a topic of concern for a number of writers. But now, as extreme weather swirls around the globe — melting glaciers, burning forests, flooding homes and annihilating species — the climate emergency has brought the unimaginable into our daily lives and literature.

Many climate fiction novels do not simply use climate change as a backdrop but explore the relationships between humanity and climate change from psychological and social perspectives, offering insights into its global nature. In Richard Powers’ Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, “The Overstory,” a research scientist suggests that trees have their own forms of consciousness and community that provide a valuable timeline for measuring human activities and their impact on the environment.

Other popular examples of cli-fi include Octavia Butler’s “Parable of the Sower,” Barbara Kingsolver’s “Flight Behavior,” Kim Stanley Robinson’s “New York 2140,” and Ashley Shelby’s “South Pole Station.” Is this climate activism?

For most people, it’s hard to imagine what the world will be like a few decades from now as the earth’s temperature continues to rise. What will happen to agriculture? To coastal communities? To international order? Cli-fi imagines the “new reality” for us and offers ways to talk about the issues.

In a review in the San Francisco Chronicle of Edan Lupucki’s novel “California,” Sarah Stone wrote that if we survive, “… it will be in part because of books like this one, which go beyond abstract predictions and statistics to show the moment-by-moment reality of … the price we may have to pay for our passionate devotion to all the wrong things.”

Mallory M. O’Connor is a professor emerita of art history at Santa Fe College in Gainesville. She is the author of six published novels, including a paranormal/cli-fi series as well as two non-fiction books. Her most recent book is “The Kitchen and the Studio: A Memoir of Food and Art” (Atmosphere Press, 2023), co-authored by her husband, artist John A. O’Connor.

If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu. Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here.