By Neil Carter and Deqiang Ma, University of Michigan

Human-wildlife overlap is projected to increase across more than half of all lands around the globe by 2070. The main driver of these changes is human population growth. This is the central finding of our newly published study in the journal Science Advances.

Our research suggests that as human population increases, humans and animals will share increasingly crowded landscapes. For example, as more people move into forests and agricultural regions, human-wildlife overlap will increase sharply. It also will increase in urban areas as people move to cities in search of jobs and opportunities.

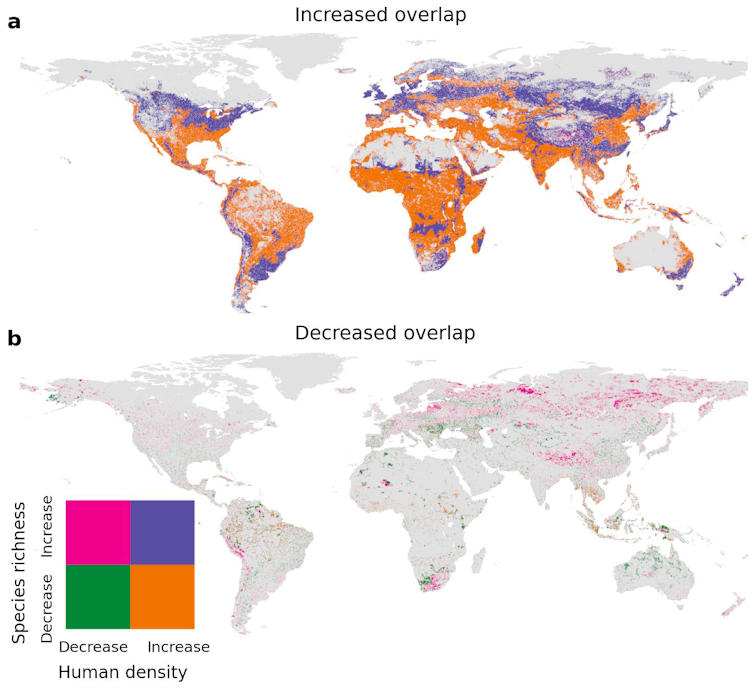

Animals are also moving, mainly in response to climate change, which is shifting their ranges. Across most areas, species richness – the number of unique species present – will decrease as animals follow their preferred climates. But because human population growth is increasing, there still will be more human-wildlife overlap across most lands.

We also found areas where human-wildlife overlap will decrease as human populations shift, although these were much rarer than areas of increase.

(Ma et al., 2024, CC BY-ND)

We found that Africa will have the largest proportion of land with increasing human-wildlife overlap (70.6%), followed by South America (66.5%). In contrast, Europe will have the largest proportion of land experiencing decreasing human-wildlife overlap (21.4%).

Why it matters

Around the world, humans and wildlife increasingly compete for limited space on land. This can lead to harmful outcomes, such as human-wildlife conflicts and the spread of diseases between humans and animals.

Interacting with wildlife, however, can also have benefits. For example, birds provide valuable pest control for some crops. And studies show that observing birds and animals in nature improves people’s mental health.

It is important to manage these interactions in ways that minimize negative impacts and maximize benefits. This is a key goal of the Global Biodiversity Framework that nations adopted in 2022 as a blueprint for conserving life on Earth and slowing the loss of wild species.

Our findings underscore the need to manage for coexistence between people and wildlife. Our research provides a broad understanding of where changes in human-wildlife overlap will occur in the future, including hot spots that will require more effective measures to improve human interactions with wildlife.

How we did our work

We developed a spatial index to measure human-wildlife overlap around the world. To calculate the degree of overlap region by region, we multiplied human population density by the number of species present in a given area. Our study included 22,374 land-dwelling species of amphibians, birds, mammals and reptiles.

By combining published datasets on most recent (2015) and future (2070) populations, species distributions and land types, we were able to investigate how human-wildlife overlap will change by 2070 and to identify the places where this overlap will increase most dramatically. We then investigated changes in species richness across each land type – cropland, grassland, urban and forest – with increasing human-wildlife overlap.

What’s next

Our research shows broadly how human-wildlife overlap will change, but researchers will need local studies to understand the consequences. Future research on shared lands should analyze factors including species abundance, species behavior and ecology, as well as types of interactions between people and wildlife.

Policymakers can use insights from our work to guide conservation planning in a more crowded future. For example, our projections can help identify locations for habitat corridors that enable wildlife to move between critical habitats. They also could help to identify areas that are relatively buffered from the effects of climate change over time and could serve as havens for at-risk species.

Our work can inform future conservation investments, such as rewilding areas where human population density is decreasing, or preserving and enhancing wildlife habitats in places that are becoming more urbanized.

Finally, our study shows the importance of engaging local communities in wildlife conservation. In our view, using many conservation strategies and taking human needs into account will be the most effective way to ensure sustainable coexistence.

The Research Brief is a short take on interesting academic work.![]() Banner photo: A giraffe in Nairobi National Park, with the city in the background. (Alexmbogo, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons).

Banner photo: A giraffe in Nairobi National Park, with the city in the background. (Alexmbogo, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons).

Neil Carter is an associate professor of wildlife conservation at the University of Michigan and Deqiang Ma is a postdoctoral researcher in environment and sustainability at the University of Michigan.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.