By Carrie Stevenson, UF/IFAS Escambia County Extension Office

If you’ve spent any time on the coast, you know we’ve got plenty of marine mammals. Dolphins will surface in pods, delighting beachgoers; they’ll bow-ride along boats and occasionally treat onlookers to a full Sea World-style leap from the Gulf. Lately, the Panhandle has seen its fair shares of manatees slowly grazing by, too.

But if you asked most folks about marine mammals in the Gulf, odds are they wouldn’t mention whales. We think of the whale-watching boats trips far away off the coast of Alaska, California, Hawaii and the Pacific northwest, or the tales of old from whale-hunting in the north Atlantic. In reality, we have at least 20 species of whales that migrate through our region, and at least one that lives permanently in the Gulf of Mexico.

An estimated 300 orcas (aka killer whales) live in the Gulf, although their habits are not well-researched. A few years ago, five pilot whales beached themselves in Pinellas County. We even get gigantic humpback whales cruising offshore in the Gulf.

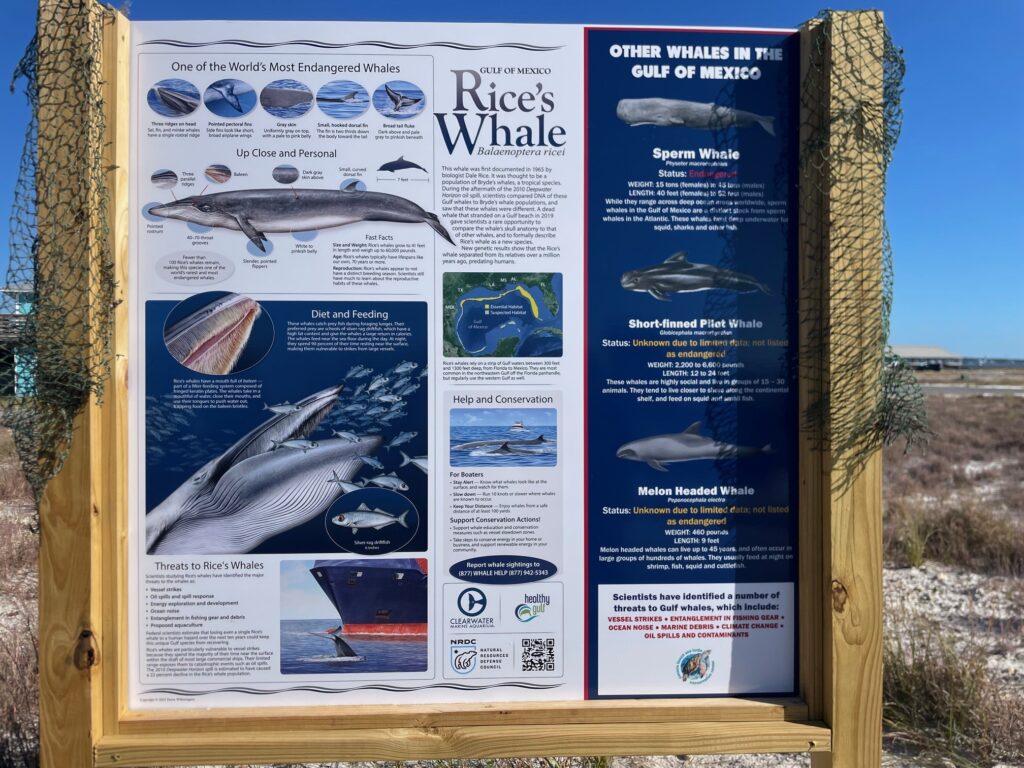

But of most recent interest is the recognition of a new species of whale in the Gulf. First identified in the mid-1960s by whale biologist Dale Rice, most scientists assumed it was part of a population of Bryde’s whales, which live in the tropics. In 2019, one beached in the Everglades, allowing biologists to conduct genetic analysis. The differences in size, shape (aka morphology), and genetics resulted in determination of a new species.

Named for its original descriptor, the Rice’s whale (Baelaenoptera ricei) is the only full-time resident baleen whale in the Gulf. As a member of the expanding (another new species was identified in 2003) taxonomic family Balaenopteridae, instead of teeth they use bristly rows of keratin called baleen to filter feed.

When hunting, they gulp large mouthfuls of fish and water, pushing it against their baleen with their tongues to sieve out the water and hang onto the fish. New research led by a team at Florida International University shows Rice’s whales prefer an oily and calorie-filled fish called silver-rag driftfish (Ariomma bondi), which help grow their massive 40-foot long, 30-ton bodies.

As air breathers, Rice’s whales spend the vast majority of their time floating and resting near the surface. They are extremely rare, with an estimated population of around 50. With such a small number, they are particularly vulnerable to boat strikes, pollution, noise and were severely impacted (22% population loss) by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Controversy often follows the discovery of a new and endangered species. Legal measures around the species impact those in the shipping and drilling industry out in the Gulf, so the whale has unwittingly found itself the subject of lawsuits between the drilling industry and environmental advocacy groups.

As always, managing natural resources is an extraordinarily complicated process (see Rick O’Connor’s deeper dive into the story here), but can be done with enough education and patience. Last spring, the inaugural Gulf Coast Whale Festival was held out on Pensacola Beach, which helped spread the word about these incredible creatures.

Carrie Stevenson is the coastal sustainability agent for the UF/IFAS Escambia County Extension Office, and has been with the organization since 2003. Banner image: One of two Rice’s whales observed by the Southeast Fisheries Science Center in the western Gulf of Mexico during an aerial survey on April 11, 2024. (Credit: NOAA Fisheries/Paul Nagelkirk, Permit #21938). This piece was originally published at https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/escambiaco/2024/10/23/weekly-what-is-it-rices-whale/.

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.