By Megan Mascheri, FAU Center for Environmental Studies

The following Q&A was conducted with Gabriel Alsenas, director of the Southeast National Marine Renewable Energy Center (SNMREC) at Florida Atlantic University. The SNMREC seeks to advance the science and technology of recovering energy from the oceans’ renewable resources, with an emphasis on resources available to the southeastern U.S. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you describe some of the things that the SNMREC does and your role as director with the center?

We’re a U.S. Department of Energy center as well as a state of Florida Center of Excellence. The Center of Excellence was established in 2006, and we became a federal center in 2010. We basically have a mission to be able to assist with the responsible development of marine energy technologies. …

We’re trying to help companies and communities to be able to bring marine energy into part of our energy mix in the U.S. For us in southeast Florida, we have a very unique opportunity here with the Gulf Stream and the section of the Gulf Stream in particular that flows by the Florida coast, called the Florida Current.

We also spend some time working on ocean thermal energy conversion. This is a process where you can take advantage of the very warm surface water, especially in tropical ocean areas, and the cold bottom water. … You can generate electricity based on collecting and discharging some of that cold water. … Here in Florida, because of the Gulf Stream and how warm it is when it flows by, we can do it in about 300 meters of water (about one-third of the depth that’s required from tropical oceans). Of course, there are … some additional engineering challenges, but it’s still compelling. …

We do need to address some of the environmental concerns that might be present. We do need to address siting issues (such as) where the best places to put pieces of equipment are for a variety of different reasons. Anything from competing uses of those areas of the ocean to what animals might be there, and how they might be more or less at risk of getting hurt with the particular equipment. …

We worked with researchers at FAU to design new ways of observing animals around equipment. Historically and traditionally, researchers have used sound waves in the water … but it wasn’t photorealistic. So, we had researchers work with underwater laser systems to be able to artificially illuminate the volume of water… so that you can actually see the animals’ behavior. …

From the economic development side, if these companies are planning to establish themselves long-term and build generation projects offshore, then they need an ecosystem of suppliers and marine service companies to bring costs down and be able to sustain them for the long term … and make it a commercial reality.

Why is it important to pursue this research further?

We have traditional renewables like solar and wind that we’re all familiar with, and one of the interesting things about those is that you see what’s called technology convergence. If someone says, “OK, I’m going to get some solar power,” we immediately think of a photovoltaic panel, right? So, we’re going to have a PV panel, we’re going to put it out in the sun, it’s going to generate electricity to power a battery or some device while it’s working.

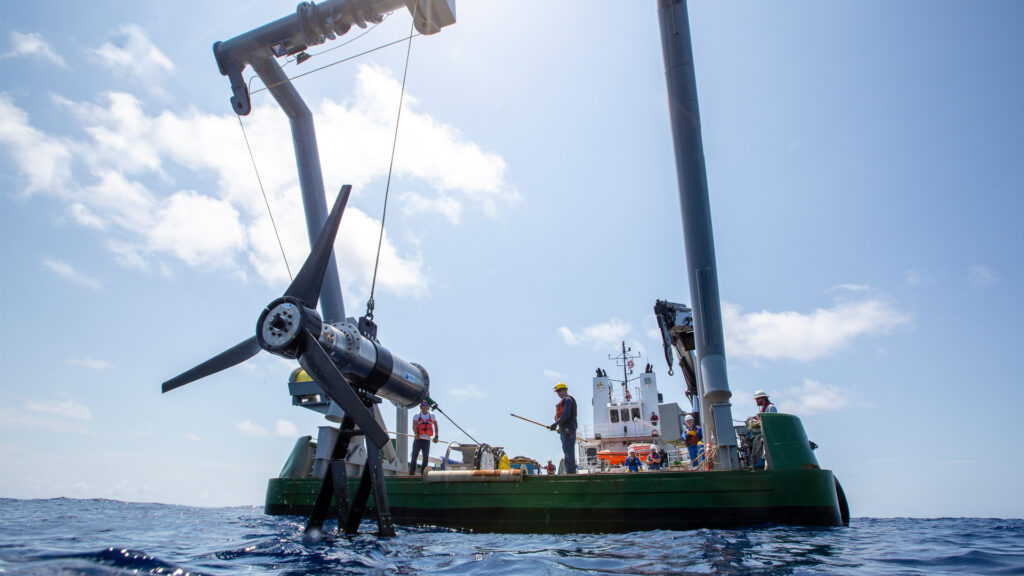

Same thing with wind, right? They’re generally amassed with a three-bladed turbine that has an up-in-the-wind-profile. We don’t have that yet with marine energy systems. There’s still a variety of different concepts and ideas, which make it interesting and need a little bit of help to get it to converge into something that we can get economies of scale for. Right now, it’s companies that are just vying for their individual market position and technology positions for it.

But why are they doing this? Why ocean currents? The other marine renewables that are very common, very familiar to a lot of people are tides (putting rotating machinery into tides near a coastline somewhere). The advantages of this are twofold: 1) it is close to shore, so you don’t have very far to bring power back to the communities, and 2) it’s usually shallower water. So, it’s less complicated and less costly to be able to install the systems.

But from the power company’s point of view, it’s intermittent, so it’s not always there. … It’s very valuable for companies to buy tidal power because they can at least predict when it’s going to be there so they can store it … and integrate it a lot easier.

Wave energy is the other common one. That’s just basically capturing the motion of the waves as they come onto our coasts. That has a lot of power potential, but it’s intermittent, just like solar and wind. … Waves aren’t as predictable as tides, and in many cases a lot of the wave energy systems are at the surface and are really visible to our communities and, depending on the community, sometimes that’s desirable, sometimes it’s not desirable.

But the Gulf Stream and other western boundary currents around the world, they offer potentially a non-intermittent power source, which is very rare for renewables. We have geothermal that could potentially do that, ocean thermal energy conversion could potentially do that, but the Gulf Stream is sort of a low-hanging fruit. The Gulf Stream is always pumping by.

We’ve been measuring it now for almost a decade and a half, and apart from temporary changes in the current for major storms, like hurricanes, it’s always there. And so, from a power company point of view, that’s compelling. You don’t need to worry about whether the sun’s shining or when the waves are coming onto shore. You can expect that power to be produced when you need it as a baseline power source. And that’s one of the huge value propositions to this.

What are some of the positive impacts the center’s efforts have on our climate?

As an industry, not just at FAU, we’ve been trying to articulate that it’s really easy to look at these projects from the point of view of how one animal or several animals might be affected by it, (which is) obviously a concern and something that we spend a lot of time working through, better understanding and mitigating. …

We’re (the industry) tapping into the natural environment. There are concerns in general about making sure that whatever natural resources we extract are surplus or don’t affect our overall resource availability around the world, so we’re not taking too much power out of the Gulf Stream, we’re not diverting it, we’re not doing something like that.

From the positive side, we can realize greater energy security. It’s all domestically grown. We don’t rely on any kind of price fluctuations or importing any kind of fuels. It’s all in our backyard. It’s all something that we naturally have available to us. …

What are the next steps regarding the research at SNMREC in the coming years?

There’s a few. One of the things is that we realized that we can probably do more than what we have had an opportunity to do. FAU on its own doesn’t have the full expertise and resources available to help out with all the other renewables also. We have some individual faculty that can do wave energy system modeling, onshore and offshore capabilities that we’re building to help companies test equipment, but it hasn’t been integrated in a way that we could say to a company, “We can help you from your concept all the way to commercialization” and (helping) them to have power-purchase agreements with power companies or mass manufacture their systems.

We’re starting to build partnerships with other universities that have been active in the space, but don’t yet have the coordination and integration for it. So, we’re looking for an expansion of our center and our partnerships at the center to be able to offer more to the industry and to the Department of Energy and to the communities. We also are looking to the future to be able to anticipate the needs of the companies as they grow. …

From the economic development point of view and the education point of view, (we plan on) creating more positive messaging about the opportunities and also helping to facilitate investors, power companies, manufacturing companies and the whole ecosystem that’s going to be needed to be able to turn this into a viable actual industry.

Instead of just having individual companies pushing forward, we need it to be an industry. And so, we’re looking to help make connections, attract supply chain companies to the region, be able to offer opportunities for investors to see the equipment and practice, and get to meet the companies and the leadership in these companies. … There’s a lot left to do on this. It’s just the beginning.

This Q&A was conducted by Megan Mascheri, a graduate research assistant at Florida Atlantic University who earned her master’s degree in its geosciences program in August. Mascheri has worked as a research assistant for FAU’s Center for Environmental Studies since 2021. The center manages and funds The Invading Sea.

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu. To learn more about using ocean currents to generate electricity, watch the video below.