By Laurie Mermet, The Invading Sea

The combination of more intense storms and rising seas poses a critical challenge for coastal infrastructure, particularly in Florida, where many communities are built near the water.

Hurricanes Milton and Helene caused major damage to coastal infrastructure, especially in the Tampa Bay area, such as Helene causing nearly 1.5 million gallons of sewage spilling in St. Petersburg and Milton leading to widespread power outages along the Gulf Coast.

Climate scientists say rising sea surface temperatures contribute to the rapid intensification of hurricanes. They stress the importance of adapting coastal infrastructure to better withstand the impact of these storms and rising sea levels.

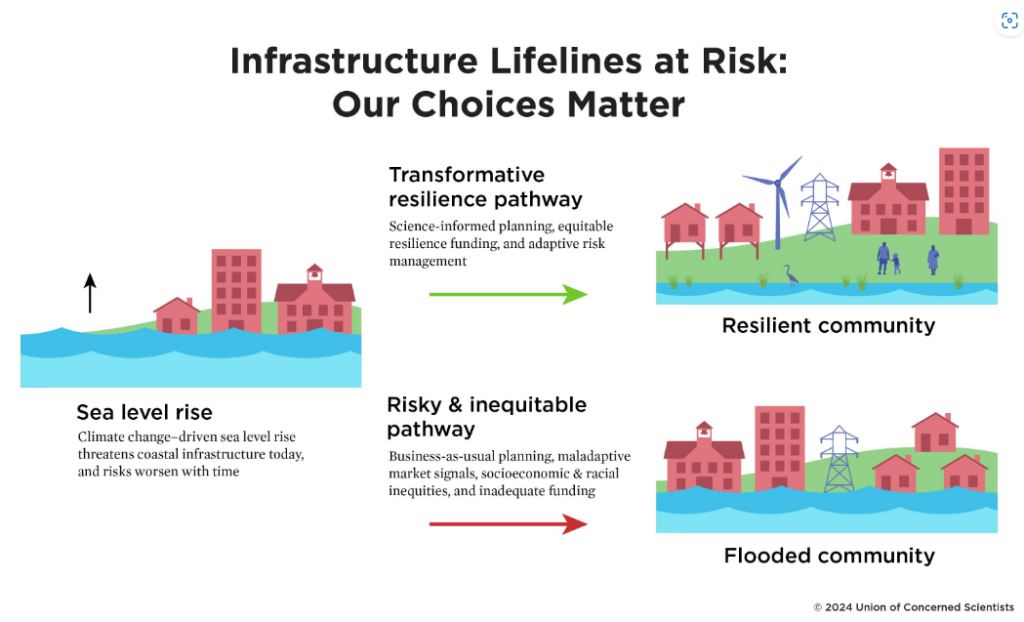

An analysis by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) found that 91 critical infrastructure assets in Florida were at risk of flooding twice a year in 2020 and projected that sea level rise will cause that number to rise sharply. Under a high sea level rise scenario, Florida is projected to have 102 critical infrastructure assets at risk by 2030 and 252 by 2050. These critical assets include wastewater treatment plants, electrical substations and health care facilities.

Kristina Dahl, a climate scientist at UCS, said that the risk of flooding is closely tied to the location of these facilities. She noted that critical infrastructure facilities, such as fire stations and wastewater treatment plants, are often located near the water, but these are essential for community functionality.

“There’s sometimes a tradeoff, because you need those sorts of facilities to be close to people and embedded in communities. …You can’t just have all of your fire stations sighted farther inland, because you have communities along the coast that need that kind of infrastructure to be accessible,” Dahl said.

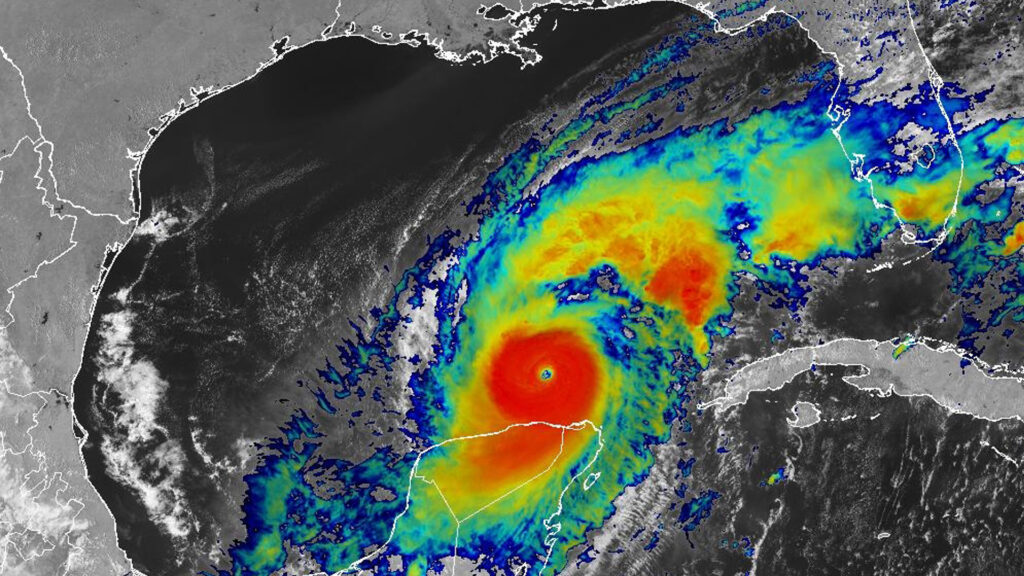

The increasing intensity of hurricanes compounds the problems. World Weather Attribution concluded that climate change made Hurricane Milton wetter, windier and more destructive.

Climate Central reported Hurricane Milton’s maximum sustained winds surged by 120 mph in just 33 hours after an initial alert on Oct. 7, fueled by abnormally warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico. Daniel Gilford, a hurricane expert and climate scientist at Climate Central, described Milton as “one of the most rapidly intensifying storms of all time.

“As we increase the temperature of the planet, we also are increasing how much moisture is in the atmosphere, and so storms like Milton can carry a lot more … water and dump water very far away from an ocean in a very short period of time and cause inland flooding,” Gilford said.

Dahl emphasized the role of rising sea surface temperatures in driving more intense hurricanes.

“We’re seeing a shift toward more hurricanes reaching the strongest categories — three, four and five — because of the warmer ocean temperatures that are enabling storms to become stronger than they would have in the past,” she said.

She explained that increased rainfall during hurricanes is a clear sign of climate change, as warmer sea surface temperatures allow hurricanes to absorb more moisture, while a warmer atmosphere retains more water, resulting in heavier downpours.

“As we increase the global sea level, we expect to see more frequent flooding during regular high tides along our coasts,” Dahl said. “But those higher seas also mean that when a storm like Helene or Milton comes through, it’s riding on this higher baseline, making storm surge deeper and able to reach farther into communities.”

The analysis by the Union of Concerned Scientists projects that by 2050, sea level rise driven by climate change will subject more than 1,600 critical buildings and services to disruptive flooding, occurring twice annually on average. The report also features an interactive map highlighting at-risk infrastructure across various U.S. cities.

In addition to water and electrical facilities, this vulnerable infrastructure includes K-12 schools, police stations and public housing. A key approach to strengthening coastal infrastructure, Dahl suggested, is building physical barriers around these facilities to make them more resilient.

“When you have facilities that are critical for a community and they have to be near the water, then things like physical defenses around that infrastructure can make a lot of sense,” Dahl said. “So, for example, wastewater treatment plants are usually located near the water in coastal states, and that’s because of the way those facilities function. … They need to be able to pump treated water back out into the ocean.”

Dahl gave the example of DC Water, a water treatment plant that has invested millions in constructing a protective seawall around its plant because such infrastructure is difficult to relocate. She said that for facilities like this, or for fire stations located on island communities, physical defenses are the most viable solution.

In particular, Dahl pointed to electrical substations as some of the most vulnerable infrastructure, stressing that this was largely due to the location of these facilities.

“Taking a power plant offline is bigger than the impact of one electrical substation going offline,” she said. “So the substation might cause outages in a neighborhood, whereas the power plant could be the whole county or multiple counties. So definitely in terms of siting our facilities, that’s really critical.”

Gilford said the timing of a hurricane’s landfall plays a significant role in its impact, with storms striking at high tide posing a greater risk than those that strike at low tide. He noted that sea level rise further influences the damage they can cause.

“Just small amounts of sea level rise can lead to big impacts when a storm rolls through, because it could be the difference between overtopping a barrier or not,” Gilford said.

Laurie Mermet is a Florida Atlantic University senior majoring in multimedia journalism who is reporting for The Invading Sea during the fall 2024 semester. Banner image: Utility crews in Bradenton repair power lines after Hurricane Milton on Oct. 13. (Liz Roll/FEMA, via Defense Visual Information Distribution Service).

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu. To learn more about how sea level rise affects drinking water infrastructure, watch the video below.