This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

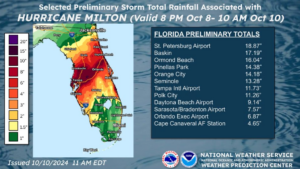

A preliminary analysis from the team of scientists at World Weather Attribution indicates the rainfall from Hurricane Milton across Florida was 20% to 30% heavier and rainfall intensity was about twice as likely as it would have been in the climate of the late 19th century.

Similarly, climate change is responsible for a 40% increase in the intensity of storms like Milton, located in the eastern Gulf of Mexico near the Florida coast, the analysis found. Effectively, Milton would have made landfall as a Category 2 storm in an earlier climate. Instead, it came onshore Wednesday night near Siesta Key south of Sarasota as a Category 3.

Like Hurricane Helene 12 days earlier, Milton met the scientific criteria for rapid intensification — an increase in maximum wind speed of 35 miles per hour in 24 hours. But Milton intensified at a truly staggering rate while over the southern Gulf of Mexico, 95 miles per hour in 24 hours. Only two other storms — Wilma (2005) and Felix (2007) — intensified faster in the Atlantic basin, the area that includes the Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean Sea and open Atlantic Ocean.

This extreme rapid intensification is projected to happen more often in today’s modern, warming climate. Seeing that data in real time led veteran South Florida meteorologist John Morales to choke up momentarily during his regular broadcast on NBC6 in Miami (WTVJ) on Monday as he described Milton’s rapid intensification — an emotionally gripping moment that has now been shown repeatedly across the internet.

Jeff Berardelli, the chief meteorologist and climate specialist at the NBC station in Tampa Bay (WFLA), understood just how unusual such a dramatic drop in atmospheric pressure was at that moment. “I know John well and was surprised. He’s not an emotional guy, usually serious and buttoned up,” Berardelli said.

But when it came to the data, both he and Morales were well aware of the forces being driven by climate change.“I was not surprised one bit,” Berardelli said. “It used to be that we meteorologists wondered if a storm would rapidly intensify. Now, we expect it to because the oceans are rip-roaring hot, due to climate change.”

Farther inland, Amy Sweezey paused as well. Currently a freelance meteorologist who has worked in central Florida for more than 20 years, she was at the NBC station in Orlando (WESH) when four hurricanes hit Florida in 2004. But earlier this week, Milton was rapidly intensifying and heading straight for her city. “I’ve seen plenty of storms intensify rapidly, but when you see it in such close proximity to your home, the feeling of dread reaches a whole new level,” she said.

Strength of hurricanes can also be based on lowest pressure. Using that measurement, Milton became the fifth-strongest hurricane on record in the Atlantic basin and the second Category 5 hurricane of the season. Since 1950, only five other years had more than one Category 5 storm in a single season. Four of those years have come since 2005.

Even though climate change may not be increasing the average number of storms in a season, there is evidence indicating the percentage of total storms reaching Category 4 is increasing, consistent with most climate modeling studies.

As forecast by the National Hurricane Center, the ferocity of Milton edged back from a Category 5 to a Category 3 in the 24 hours before the eye came ashore near Siesta Key, 25 miles south of Tampa Bay.

In those last 24 hours, Milton moved into an area with stronger jet stream winds higher in the atmosphere, which began to tear at the symmetric structure around its eye. This rapid change in wind speed with height, known as wind shear, effectively works to pull apart the core circulation of the storm.

But it may have worsened another aspect of the storm. Hurricanes approaching land usually produce tornadoes in their outer spiral bands, and that shear may have made them worse.

“The jet stream started interacting with Milton, imparting extra dynamics which turned what would normally be weak, barely noticeable tornadoes, into a real tornado outbreak resembling something you’d see much farther north in the Southeast U.S.,” Berardelli said.

Wind shear from an approaching branch of the jet stream helps individual thunderstorms within those spiral bands rotate, increasing the threat of tornadoes. More analysis will be needed, but this may have contributed to the especially strong tornado outbreak across south central Florida preceding the hurricane.

Tornadoes do not have a direct relationship to climate change. Compared to larger storms like hurricanes, their size is much smaller and their lifespan much shorter, making their connection to the warm climate more challenging to determine. However, there are signs that the broader conditions that favor tornado formation are happening more frequently, especially outside of the traditional spring and early summer tornado season.

Misinformation and conspiracy theories have been running rampant on social media since the catastrophic Appalachian flooding from Hurricane Helene. Suggestions that the government created and directed hurricanes for political purposes have no basis in reality. Both Berardelli and Sweezey have seen plenty of misinformation while trying to convey life-saving information on social media, but as professionals, they are able to work past the noise.

“I am not new to conspiracy theories and viral social media posts,” Sweezey said. “But I was surprised at how many there seemed to be with this particular storm. Those of us who were here in 2004 still remember the damage from Charley and the trifecta. I think that memory is what encouraged many people along the Gulf Coast to evacuate.”

Knowing he was closer to the landfall point, Berardelli was also able to concentrate on getting the essential information out. “With the storm heading directly at my community, I needed to keep my head down and my message clear,” he said.

There are no hurricane threats to the continental United States for at least a week, according to the latest weather data, with the 60-day heart of the hurricane season, between mid-August and mid-October, nearly over. But the season continues until the end of November, the Gulf of Mexico remains warm and Florida’s battle-tested meteorologists are well aware that they must keep watch for new developments for at least several more weeks.

Banner photo: After Hurricane Milton, many streets in Tampa were flooded and closed. The pictured street was still closed four days after the storm. (Liz Roll/Federal Emergency Management Agency, via Defense Visual Information Distribution Service). This piece was originally published at https://insideclimatenews.org/news/12102024/climate-change-made-hurricane-milton-stronger/.

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.