This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. It is republished with permission. Sign up for their newsletter here.

By Amy Green, Inside Climate News

ORLANDO, Fla. — The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service last week proposed expanding habitat protections for ailing manatees, which in Florida have suffered in recent years through extraordinary habitat challenges that have left the sea cows emaciated and dying.

The update to the manatee’s critical habitat would be the first since the animal was protected under the Endangered Species Act in 1976, according to the Center for Biological Diversity, one of three conservation groups that brought a lawsuit to pressure the federal agency to take action. Critical habitat is a legal term encompassing waterways considered vital to the manatee’s recovery. The West Indian manatee, of which the Florida manatee is a subspecies, was downlisted in 2017 from endangered to threatened.

Nearly 2,000 manatees died in Florida in 2021 and 2022 — a two-year record. The calamity prompted wildlife agencies to go so far as to provide supplemental lettuce for starving manatees in the 156-mile Indian River Lagoon on the state’s east coast, where water quality problems have led to widespread seagrass losses. Conservation groups said the deaths represented more than 20 percent of the state’s population. This year more than 130 manatee calves have died in the state.

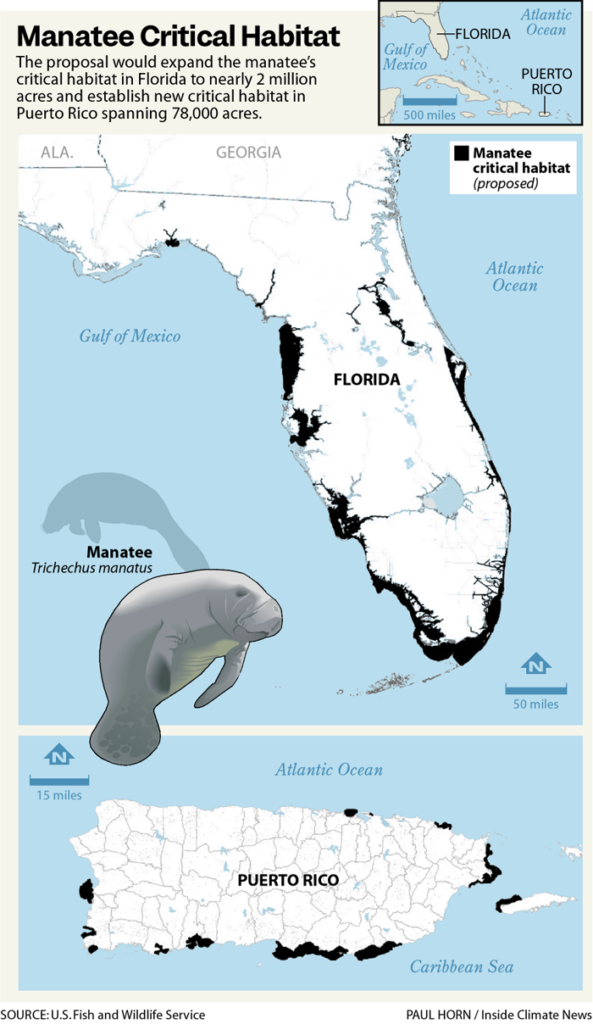

The proposal would expand the manatee’s critical habitat in Florida to nearly 2 million acres and establish new critical habitat in Puerto Rico spanning 78,000 acres. Notably, the proposal for the first time emphasizes the significance of habitat features such as seagrass and natural warm-water sites, said Ragan Whitlock, staff attorney for the Center for Biological Diversity.

The warm-water sites such as springs are of growing importance for the cold-sensitive manatees as power companies consider moving away from fossil fuels because of climate change. The transition is likely to affect warm waters around power plants where manatees gather during the winter. Whitlock characterized the new critical habitat proposal as an important step.

“Back in the day it really just looked like a list of places where we knew manatees congregated,” he said. “It was not even a full page and didn’t provide any insights into the current threats.”

A critical habitat designation prohibits any federal agency from permitting, funding or carrying out any action that would adversely affect the habitat, although it does not affect land ownership or establish a refuge or preserve.

The Center for Biological Diversity, Defenders of Wildlife and Save the Manatee Club had petitioned the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) in 2008 to update and strengthen the manatee’s critical habitat, and in 2009 and again in 2010 the federal agency acknowledged the update was warranted. But at the time FWS said the agency lacked the funding for the effort because of “higher priority actions such as court-ordered listing-related actions and judicially approved settlement agreements,” according to the groups.

Manatees face several important habitat threats. Harmful algae blooms, like those in the Indian River Lagoon that are responsible for the seagrass losses, likely will worsen as waters warm because of climate change. Some of the blooms, like red tide, are toxic and can poison the manatees. Florida’s springs, with temperatures that remain constant throughout the year, are experiencing water quality problems and diminishing flows, as they are pressured by groundwater withdrawals for bottling, industrial and residential use.

“Manatees are one of those species that can help their entire ecosystem be protected, and that people want to be a part of doing that,” said Pat Rose, executive director of the Save the Manatee Club. “Manatees have at least brought much greater attention to how bad things have gotten.”

The unprecedented number of manatee deaths in Florida in 2021 and 2022 triggered multiple lawsuits. A federal judge last week declined to dismiss one of those lawsuits, which was against the Florida Department of Environmental Protection over sewage discharges in the northern Indian River Lagoon. Bear Warriors United, a wildlife advocacy group, had accused the state of violating the Endangered Species Act by failing to regulate the effluent, a primary factor in the pollution responsible for the harmful algae blooms and seagrass losses.

The state argued the lawsuit should be dismissed because the group lacked standing, among other reasons. But Judge Carlos Mendoza disagreed, contending the state was responsible for regulating wastewater treatment facilities and septic tanks and that the problems were traceable to the state’s actions.

Meanwhile, FWS told Inside Climate News this week that work continues on an in-depth status review and analysis on the manatee’s classification. When the federal agency downlisted the manatee in 2017 to threatened, the agency said it was because gains in the animal’s population and habitat meant its status no longer fit the definition of endangered.

The decision generated widespread outcry, and last October the agency announced it would issue a 12-month finding on whether reclassification back to endangered was warranted, after concluding a petition demanding the change presented substantial scientific evidence.

The petition was filed by the Save the Manatee Club, the Center for Biological Diversity, Harvard Animal Law & Policy Clinic, Miami Waterkeeper and Frank S. González García, a concerned citizen. The federal agency said it hoped for a finding by the end of the year.

Florida manatees are found along the coasts of the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico and in the Caribbean from the Bahamas to Turks and Caicos. Antillean manatees range from Cuba, Hispaniola, Jamaica, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands to Mexico, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago and Brazil. Both subspecies of the West Indian manatee are very similar, although the Florida manatee typically is larger. The critical habitat proposal involves both subspecies.

FWS is accepting comments on the proposal through Nov. 25. Requests for public hearings must be received by Nov. 8.

Amy Green covers the environment and climate change from Orlando, Florida. She is a mid-career journalist and author whose extensive reporting on the Everglades is featured in the book “Moving Water,” published by Johns Hopkins University Press, and podcast “Drained,” available wherever you get your podcasts. Amy’s work has been recognized with many awards, including a prestigious Edward R. Murrow Award and Public Media Journalists Association award.

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu. Banner photo: A manatee swimming (iStock image). To learn more about harmful algal blooms, watch the video below.