By Ron Cunningham

In his debut novel “Godspeed Cedar Key” Michael Presley Bobbitt imagines his beloved island village plunged by nuclear war into a more primitive state – without electricity, running water, sanitation or contact with the outside world.

But when Hurricane Helene came calling, Bobbitt stood chest deep in surging water and bore witness to a real force of nature that did far more damage than his novel contemplated.

Bobbitt choked back tears as he stood amid the ruins on the morning after. “However bad we imagined it would be when we were fighting in the darkness, it’s so much worse in the daylight.”

He saw iconic businesses destroyed, public buildings washed away and homes reduced to rubble.

Rebuilding Cedar Key, he said, will not be the work of months but rather years. And Bobbitt fears the destruction will cause many island residents to leave for good.

“We will see who loves Cedar Key,” he said.

Still, on the day after Helene did its worst, Bobbitt, self-proclaimed Cedar Key “Clambassador,” vowed that the town will rebuild.

What worries me, and should worry Bobbitt and his neighbors, is how a resurrected Cedar Key will look, and function. And who will be able to afford to live there.

The magic of Bobbitt’s Cedar Key is that it is a blue collar town of working-class people who make their living off the shallow waters that surround the island.

For good reason Bobbitt calls it the “Anti-Siesta Key,” in reference to the Sarasota resort island where people go to party, bask on the beach and retire in condos.

Still, it wasn’t all that long ago when Florida novelist John B. McDonald’s beloved Siesta Key was mostly an unpretentious collection of fishing shacks. Not unlike Cedar Key.

And we don’t have to reach back even that far to see what happens to Florida seaside towns that manage to rise again after a hurricane. Consider Mexico Beach.

During my brief stint as a bicycle tour director I loved taking cyclists to “old” Mexico Beach, just west of Port St. Joe on Florida’s Forgotten Coast.

The charm of Mexico Beach was that it largely consisted of circa-1950s era houses, hotels and businesses rather than high rises and cookie-cutter condos.

It was as though Mexico Beach had been frozen in time. Until Hurricane Michael obliterated it in 2018.

Two years ago I cycled back into Mexico Beach. And I discovered – well, a cookie-cutter condo community that bore very little resemblance to the charming town that had been there before.

How has Mexico Beach changed? Consider this 2022 Los Angeles Times headline: “A tiny Florida beach town is rebuilding after a hurricane: Is it becoming a preserve of the rich?”

It will be wonderful if Cedar Key can be resurrected so that the second, third and fourth generation families that have been there all along can remain in place, to pass their island legacy onto the next generation.

But the reality is that the homes, businesses and infrastructure that will replace what has been destroyed will be more expensive to build, if only because they’ll have to conform to modern building code standards.

And for good reason: In an era of warmer oceans, rising sea levels and increasingly more powerful storms, it would be foolish to keep building things that are likely to be swept away come the next tempest.

We should be asking whether it’s wise to rebuild a vulnerable island town that has been repeatedly brutalized by wind and waves and will likely be so again.

In a more rational society, when a beachside community is destroyed, it would be seen as an opportunity to effect a gradual retreat from our shifting, eroding shorelines and barrier islands. Government’s role should be to make hurricane victims whole again – on the condition that they build further inland.

But in Florida, when a beach town is wiped out, the political and economic pressure to redevelop it is as relentless as a Helene.

Cedar Key’s dilemma is simply this: Can it rebuild without inadvertently turning itself into a mini-Siesta Key or a more secluded Mexico Beach?

I fear that if Cedar Key rises again, the only people who can afford to be there will be tourists, retirees and wealthy people looking for a secluded weekend retreat.

I hope I’m wrong. History suggests otherwise.

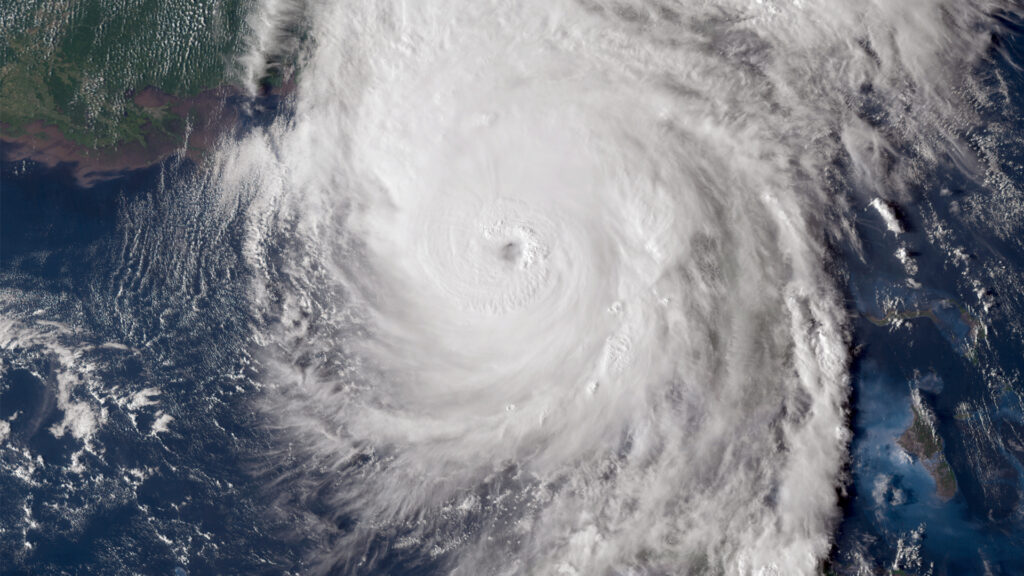

Ron Cunningham was editorial page editor of The Gainesville Sun for 30 years. Banner photo: Cedar Key before Hurricane Helene (iStock image).

If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu. Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here.