By Dyllan Furness, Florida Flood Hub for Applied Research and Innovation

Sea surface temperatures are on the rise around the world, but the problem is pronounced in the estuaries and shallow coastal waters of South Florida.

In South Florida, estuaries have experienced rapid warming over the past two decades. These temperature changes have outpaced trends elsewhere in the ocean, according to a series of studies published by researchers at the University of South Florida College of Marine Science (CMS) and National Park Service.

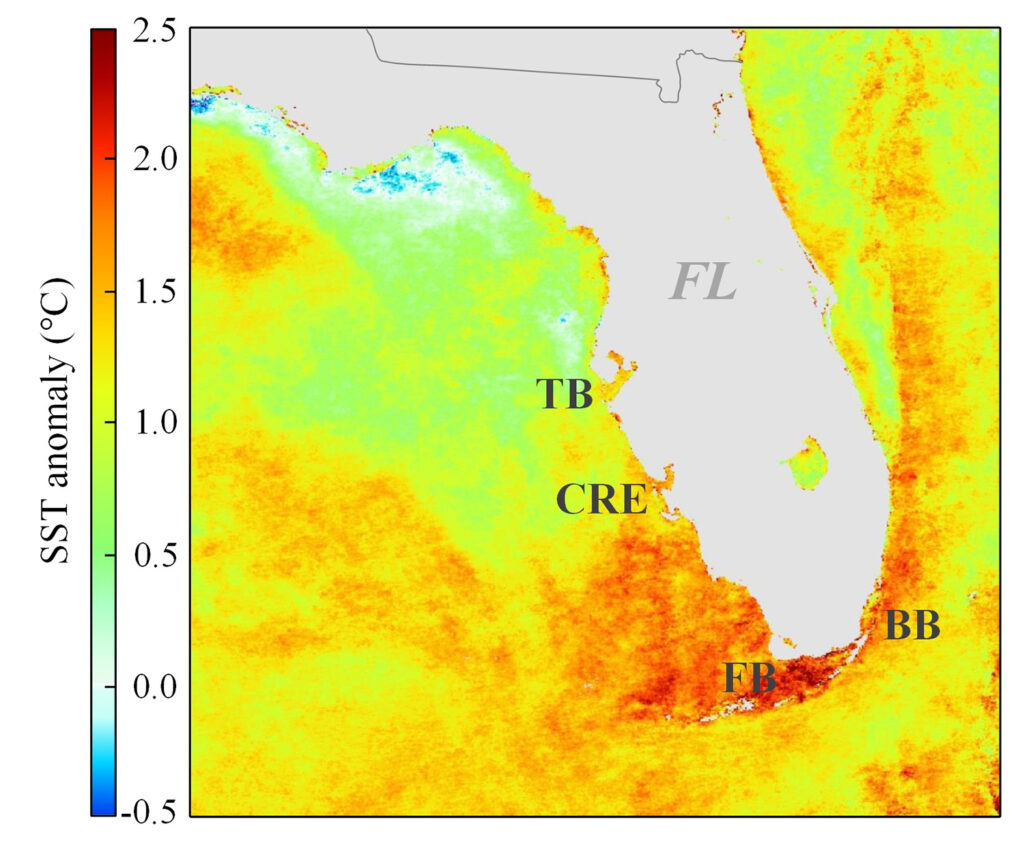

Using satellite data, the researchers found that sea surface temperatures in four estuaries in South Florida have risen faster than sea surface temperatures in global oceans and the Gulf of Mexico. The findings, published in Environmental Research Letters and Estuaries and Coasts, paint a troubling picture for the marine life that calls Florida home.

“The temperatures in South Florida estuaries are not only rising faster than the global average, but also faster than temperatures in the open Gulf of Mexico,” said Chuanmin Hu, professor of physical oceanography at CMS and co-author of the recent papers. “We even saw more of a response within the estuaries to last year’s marine heat wave.”

Over the past two decades, sea surface temperatures in Florida Bay, Tampa Bay, St. Lucie Estuary and Caloosahatchee River Estuary rose around 70% faster than the Gulf of Mexico and 500% faster than the global oceans, according to the authors. These temperatures are expected to take a toll on marine life.

Estuaries are nurseries, where many marine animals begin their lives. South Florida’s estuaries are home to critical habitats such as seagrass meadows, and adjacent waters in the Florida Keys are home to world-renowned coral reefs. These may be impacted by rising water temperatures.

“Algae, seagrass and coral are all sensitive to temperature changes,” said Hu. “Algae often grow faster in warm water, which can increase the size and frequency of blooms. Meanwhile, seagrass and coral undergo stress if the water gets too warm.”

The researchers hope to partner with colleagues at the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to explore the potential impacts of water temperatures on seagrass and coral populations in South Florida.

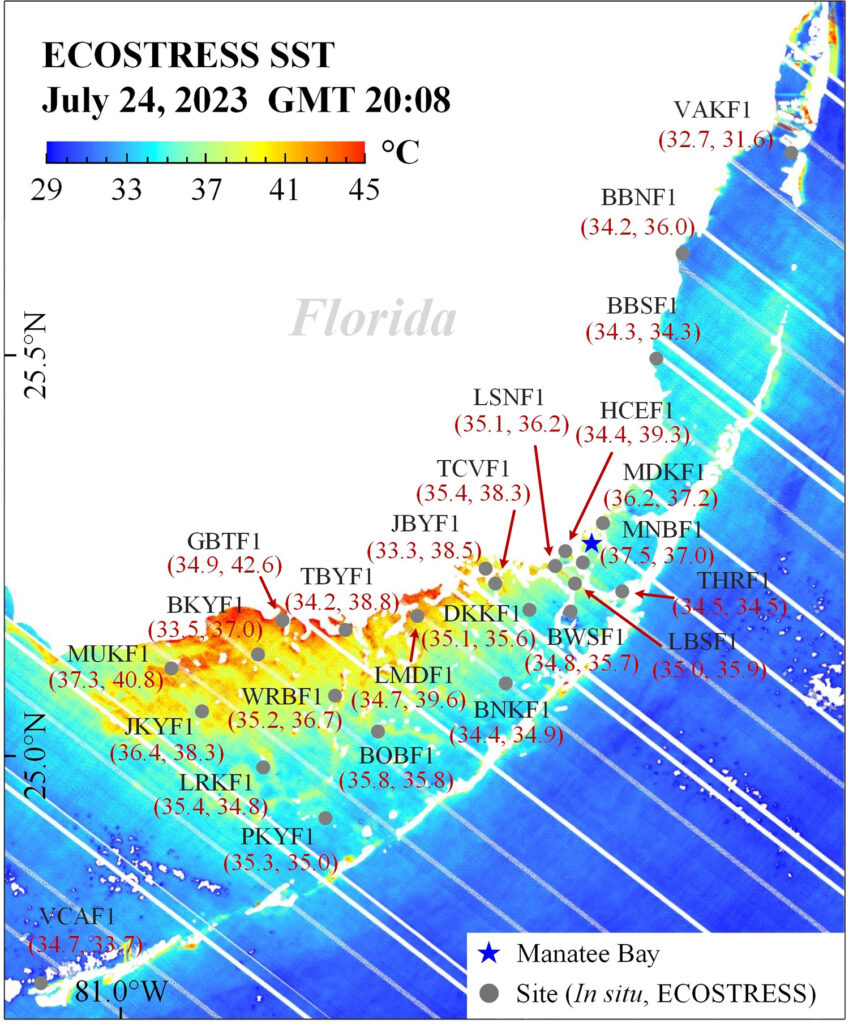

Jing Shi, a doctoral student in Hu’s lab and first author of the papers, spent more than a year identifying the best datasets to shed light on the study. After extensive evaluations, she landed on two datasets: MODIS and ECOSTRESS. The MODIS dataset allowed Shi to study long-term trends of water temperature in South Florida’s estuaries since 2002, while the higher-resolution ECOSTRESS dataset enabled her to detect temperature changes between local waters in each estuary.

“Using the right data is critical,” Shi said. “If you don’t use the right data, you might get the wrong conclusion.”

The researchers speculated on possible causes for the high rate of warming in South Florida’s estuaries, including evaporation, water capacity and residence time (the amount of time water spends in an estuary). No single factor has been revealed as dominant.

Ongoing research by Hu and Shi will investigate another peculiar observation: the accelerated warming seen in South Florida’s estuaries has not been detected in many other estuaries across the region.

“Not every estuary around the Gulf of Mexico is behaving this way,” Hu said. “These temperature changes appear unique to the estuaries of South Florida.”

The next question, Hu said, is how long this faster warming in South Florida will be sustained.

“We expect the rate of warming to eventually balance with the open Gulf of Mexico,” he said. “We just don’t know when that will happen.”

This research was supported by grants from the NASA Water Resources Program and NASA ECOSTRESS Program, and a USF presidential fellowship.

Dyllan Furness is science communication manager for the Florida Flood Hub for Applied Research and Innovation. This piece was originally published at https://www.usf.edu/marine-science/news/2024/estuaries-in-south-florida-are-warming-faster-than-the-gulf-of-mexico-and-global-ocean.aspx. Banner image: Florida Bay, A one of the South Florida estuaries where recent studies found that sea surface temperatures are rising rapidly. Credit: National Park Service

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu. To learn more about storm surge, watch the video below.