This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. It is republished with permission. Sign up for their newsletter here.

By Amy Green, Inside Climate News

ORLANDO, Fla. — Tucked away in an office park hundreds of miles from the southeast Florida coast where North America’s only barrier reef is at dire risk, a collection of brain corals performed a once-a-year feat — producing a constellation of egg sacks, each a bundle of hope.

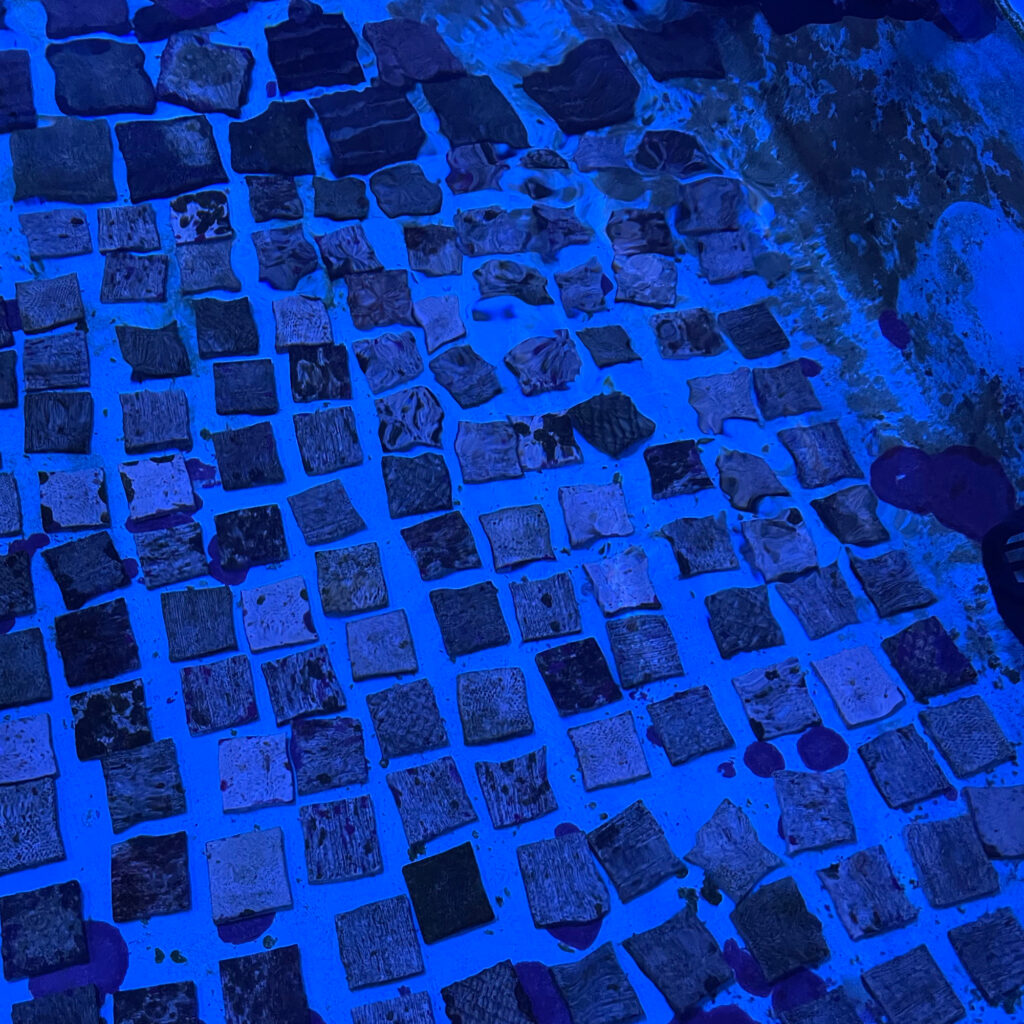

The brain corals, with their geometric design of grooves, are among more than 500 coral specimens arranged within rows of tanks inside the Florida Coral Rescue Center, a facility staffed by SeaWorld and funded by Disney, the Fish and Wildlife Foundation of Florida and the Association of Zoos and Aquariums. The nondescript facility is situated a few miles from the theme parks, off a congested highway.

The half-dozen conservationists gathered here on a recent evening had invested a year’s worth of work in the event. They calibrated the lighting to emulate the days, nights and seasons of the Florida Keys, from where many of the corals were rescued. And they maintained the water inside the tanks to ensure the chemistry and temperature were precise, to recreate conditions that would signal to the corals it was time to spawn.

The conservationists succeeded. Slowly the egg bundles, each no larger than a pea and filled with 10 to 15 eggs, rose to the surface, where they were collected with nets. In time the eggs would be fertilized and baby corals raised in hopes of eventually applying them to the reefs.

“You don’t get a second chance. You have one chance a year to hit your mark,” said Justin Zimmerman, aquarium supervisor at the Florida Coral Rescue Center and SeaWorld Rescue Center, a separate facility. “There is some stress knowing that your entire year’s work depends on collecting these eggs one night or two nights of the year.”

An unprecedented marine heat wave last summer that ravaged Florida’s fragile reefs has upended restoration efforts across the state, prompting conservationists to preserve and propagate more of the sensitive corals on land, away from the waters that rapidly are becoming uninhabitable for them.

“The way that we’ve done it in the past does not appear that it’s going to be helpful into the future,” said Margaret Miller, research director at SECORE International, a conservation nonprofit. “The environment is revealing itself to be not viable for many species.”

The heat wave stunned conservationists not only for its intensity but duration. It was the longest marine heat wave documented in three decades, characterized by the hottest ocean temperatures ever recorded in Florida, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

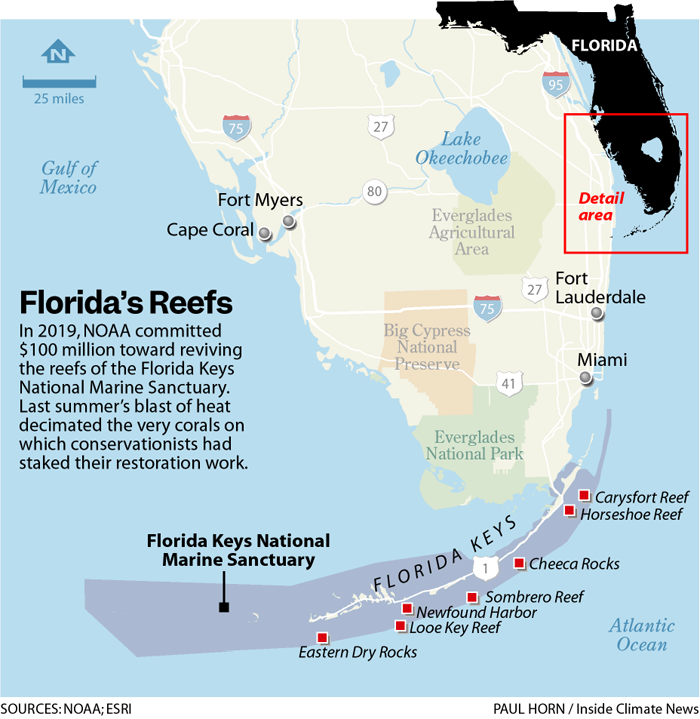

In the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, less than 22% of the staghorn corals raised in offshore nurseries for the purpose of restoring the ailing reefs remained alive after the heat had passed, and only at the two northernmost reefs: Carysfort Reef and Horseshoe Reef. Elkhorn corals similarly raised in offshore nurseries and applied to the reefs also were devastated, surviving only at three of five: Carysfort Reef, Sombrero Reef and Eastern Dry Rocks.

Both species, with branches that appear to reach up and out like the fingers of an open hand, are designated as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. The losses have been heart-rending for Maurizio Martinelli, coordinator of Florida’s Coral Reef Resilience Program for Florida Sea Grant, a research organization of the University of Florida.

“These are animals or ecosystems that we either study or have devoted careers to conserving because we love them,” he said. “Seeing those animals and this ecosystem go through these really intense events, go through these really drastic changes, seeing the kind of mortality that we see, it is hard. You finish your day of work sometimes and stare blankly at the wall because you need a moment to just process everything that’s going on.”

Heat affects corals by breaking down their relationship with the microscopic algae living inside them. The algae provide the corals both their vibrant hues and food, but when waters are too warm the corals expel the algae and turn white, a process called bleaching.

Corals can survive bleaching if water temperatures normalize quickly enough, although the process can leave them weakened, a problem poised to worsen as the global climate warms. Last summer’s widespread bleaching in Florida was part of a global bleaching event,the second in 10 years—involving every major ocean basin on Earth, according to NOAA.

“Most of the climate models and the ocean models said we weren’t going to face this situation until 2035, until 2050,” Miller said. “I really think we’re at this stage (where) parking the corals on land is really the best option that we have until we get the environment, until we get the ocean, back to a situation where it can support corals.”

Conservationists had feared even worse heat this summer, as the year began with water temperatures that continued to set records. By June, temperatures within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary had exceeded the threshold where bleaching can occur, although heavy rains cooled the waters. With recent temperatures creeping back beyond the bleaching threshold, some corals are paling, a precursor to bleaching.

“Things are in better shape at this time compared to this time last year,” said Katey Lesneski, research and monitoring coordinator for Mission: Iconic Reefs, a NOAA program.

Florida’s Coral Reef is the third-largest barrier reef in the world, stretching some 360 miles from Dry Tortugas National Park north past West Palm Beach. A portion of the reef lies within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, which spans more than 3,800 square miles and encircles the string of islands that constitute the Florida Keys.

“There’s something about coral reefs that are incredible,” Martinelli said. “It is these underwater cities of beautiful bright corals that are teeming with life. There is energy. There is sound. It’s such a special, amazing, beautiful natural wonder that we have.”

The reef teems with lobsters, sea turtles and fish, although the coral cover has declined by more than 90% over the last 40 years. Hurricanes have ripped through the corals, and boat groundings have crushed them. Pollution, disease and heat have further stressed the corals.

For more than a decade, restoration efforts centered in large part around staghorn and elkhorn corals because of their characteristic branches, which can be broken off and grown separately into new corals, a process that constitutes cloning. Often the limbs were taken to offshore nurseries where they were suspended from ropes and cultivated to a point where they were returned to the reefs. The process was pioneered in Florida by Ken Nedimyer, technical director at Reef Renewal USA, a restoration group, and now is practiced throughout the world.

“They’re easy, like growing weeds,” he said. “Anybody can do it.”

These efforts began to evolve in response to a series of smaller bleaching events and the spread of the highly lethal stony coral tissue loss disease, which was first reported in 2014 in Florida and now is found throughout the Caribbean. Some 2,000 corals that were spared of the disease and bleaching were removed from the reefs and taken to 19 zoos and aquariums from Florida to California, where they could be propagated and their genetic diversity preserved.

In 2019, NOAA launched Mission: Iconic Reefs, a $100 million program billed as one of the largest investments in reef restoration in the world. The project aimed at rescuing seven iconic reefs in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary: Carysfort Reef, Horseshoe Reef, Cheeca Rocks, Sombrero Reef, Newfound Harbor, Looe Key Reef and Eastern Dry Rocks.

Under the program, nearly half a million hand-reared corals would be affixed to the sanctuary’s reefs over the next two decades, beginning with elkhorn corals, which grow relatively quickly and are not susceptible to stony coral tissue loss disease. Slower-growing corals such as star, brain, pillar and staghorn corals would be added later. Volunteer divers would help manage marine debris and nuisance species and also help reattach damaged or broken corals.

Last summer’s blast of heat decimated the corals conservationists had staked their restoration work on. Because many of the corals had been cloned, they lacked the genetic diversity that might have bestowed on them some resilience to withstand the heat.

Conservationists rushed to save the offshore nurseries. Some were moved to cooler depths, while others were evacuated to land-based facilities. Artificial shades were used to shelter the delicate corals from the sun’s sharp glare. Without these interventions, the last wild elkhorn and staghorn corals left in the Florida Keys might have been lost, NOAA said.

“We were just taken by surprise last year,” Miller said, noting that water temperatures typically peak in August and September. “We had never seen corals bleaching in July before.”

Coral reefs are crucial to marine biodiversity and serve as important buffers that protect the shorelines from the violence of storms. In the Florida Keys more than one of every two jobs are connected with the marine ecosystem, according to NOAA.

Amid the rubble of last summer’s disaster, conservationists have found hope in the corals that survived, namely massive, brain and boulder corals. Conservationists now are focused on understanding why these species fared better and how their reproduction can be fostered through the natural process of spawning rather than cloning, to improve their genetic diversity.

“This process of adapting to a two-degree warmer temperature would normally take hundreds and hundreds of years,” Nedimyer said of the corals. “We need to make it happen in 10.”

At a Florida Aquarium facility outside Tampa, conservationists are concentrating on spawning and studying the traits of the offspring to identify those with the most resilience against heat and disease. Since last summer, fewer of the hand-reared corals have been transferred to the reefs, but some have made the journey because conservationists want to see how they will do, said Keri O’Neil, director and senior scientist of the Coral Conservation Program at the Florida Aquarium.

“We want the ocean to tell us what corals can live through this,” she said. “There really is no better laboratory than the ocean.”

Nonetheless, some see the work as futile as long as the oceans continue to warm.

“It’s buying time to solve the real problem, which is keeping our oceans or getting our oceans back to a state where they are viable for coral reef communities,” Miller said. “The solution is we have to fix climate change and maintain the water quality of our oceans.”

The Florida Coral Rescue Center in Orlando houses the largest number of corals rescued from Florida waters. The 2,000-square-foot facility contains some 20 species, and each specimen is labeled with the precise spot it came from. Fish such as blue tang, blue and black with a streak of yellow across the tail, help conservationists maintain the tanks by eating harmful algae.

“This is a true ecosystem,” said Zimmerman, the aquarium supervisor.

The facility is a veritable Noah’s Ark of Florida’s coral reefs, anonymously assembled off a bustling central Florida highway. Conservationists hope it will preserve genetic diversity so they can restart certain populations, should it come to that.

Zimmerman said the conservationists have only just gotten started, but already the corals appear to be spawning better every year. Other species will spawn in August and September.

“We can’t give up,” he said. “Their demise is happening so rapidly.”

Amy Green covers the environment and climate change from Orlando, Florida. She is a mid-career journalist and author whose extensive reporting on the Everglades is featured in the book “Moving Water,” published by Johns Hopkins University Press, and podcast “Drained,” available wherever you get your podcasts. Amy’s work has been recognized with many awards, including a prestigious Edward R. Murrow Award and Public Media Journalists Association award.

This story was produced in partnership with the Florida Climate Reporting Network, a multi-newsroom initiative founded by the Miami Herald, the South Florida Sun Sentinel, The Palm Beach Post, the Orlando Sentinel, WLRN Public Media and the Tampa Bay Times.

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.