By Courtney Lindsay, ODI; Emily Wilkinson, University of the West Indies, Mona Campus; and Matt Bishop, University of Sheffield

Hurricane Beryl laid waste to communities – even whole islands – as it barreled through the Caribbean last week. Never has such a powerful Atlantic hurricane arrived this early in the year: The ocean is usually too cool.

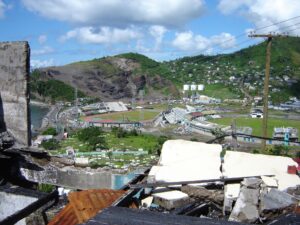

Smaller islands like Carriacou and Petite Martinique (population: 10,500) and Union Island (population: 3,000) have been decimated. Even those islands that did not receive the full brunt still suffered severe damage to infrastructure, homes, tourism and the fishing industry.

The worst may be yet to come. Five months remain of “a hyperactive hurricane season” with Atlantic temperatures at record highs. Beryl’s timing and severity imply a very long few months of torment for Caribbean people and some climate scientists predict between four and seven major storms of category 3 or more.

But even this “extraordinary” season may become somewhat ordinary by the middle or the end of the century. Beryl is, in this sense, a disturbing harbinger of what is to come as global sea-surface temperatures keep rising.

A sense of injustice

As a group, the world’s 57 “small island developing states”, about half of which are found in the Caribbean, contribute less than 1% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Yet our research finds these island states collectively experience yearly economic losses of at least $1.7 billion due to climate change. So there is a palpable sense of injustice in having to repeatedly clean up an ever-worsening mess not of the islands’ own making.

As Grenada’s prime minister, Dickon Mitchell, put it: “We demand and deserve climate justice. We are no longer prepared to accept that it is OK for us to constantly suffer significant loss and damage arising from climatic events and be expected to borrow and rebuild year after year while the countries that are responsible for creating the situation sit idly by with platitudes and tokenism.”

By the time Beryl arrived, Grenada had already spent 20 years recovering from Hurricane Ivan (2004), a disaster that cost a staggering 200% of GDP and precipitated a debt crisis. In neighbouring Dominica, Hurricane Maria (2017) caused damage worth 226% of GDP: it is now one of the most heavily indebted countries in the world.

Ponder these figures: can you envisage a remotely comparable event – short of nuclear Armageddon – that could cause damage on a similar relative scale in larger, richer states, and do so repeatedly?

Debt-disaster-debt

Flood waters remain, and the full impact of Beryl is yet to be assessed. But one thing is clear, the cost will be far higher than these countries and their citizens can afford. Disaster funds have been dusted off in Grenada and St. Vincent and the Grenadines, alongside public appeals for cash donations to restore services, but support will be insufficient and governments will have to take on yet more debt for rebuilding.

These extremely high public debt burdens are not due to fiscal profligacy. Rather, they are an inevitable outcome of the vicious debt-disaster-debt cycle in which small island nations are trapped, constantly borrowing – often at expensive commercial rates – simply to recover before the next hurricane arrives.

This leaves less to spend on things like education, health care or infrastructure. To achieve their development goals, small island developing states need to increase social spending by 6.6% of GDP by 2030. However, debt service and repayment costs gobble up an average of 32% of revenue. Indeed, in 23 of these states for which data is available, service payments on external public debt are growing faster than spending on education, health and capital investment combined.

The rest of the world must help

Small island developing states cannot – and should not – have to solve this problem alone. The international community has a historical responsibility and moral duty to help them escape from the debt-disaster-debt cycle, and to finance basic services, invest in development and adapt to a changing climate.

Donors can do a number of things. They can provide aid, rather than loans, and much more of it. They can help island states access types of financing from which they are often excluded due to their misleadingly high levels of income per capita (often skewed by one or two very rich residents).

Donors can help reduce the excessively high and unaffordable interest rates that island states have to pay on debt. And, as our work demonstrates, rich countries can provide immediate debt service cancellation (not deferment) after a shock of Beryl’s magnitude, to free up valuable fiscal space for relief and reconstruction.

Small island developing states require nothing less than a Marshall plan to finance their future. If the United Kingdom’s new prime minister and chancellor, Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves, are looking for an issue on which to demonstrate real global leadership, Hurricane Beryl has provided it.![]()

Courtney Lindsay is a senior research officer, global risks and resilience, with ODI ; Emily Wilkinson is director of the Resilient and Sustainable Islands Initiative at ODI and co-director, Caribbean Resilience and Recovery Knowledge Network at the University of the West Indies, Mona Campus, and Matt Bishop is a senior lecturer in international politics at the University of Sheffield.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.