By Natalie van Hoose

Nutrients from fertilizers and animal waste can move from Florida farms to waterways, fueling harmful algal blooms. But assessing farms’ nutrient pollution – and gauging the success of the state’s efforts to reduce it – remains a significant challenge.

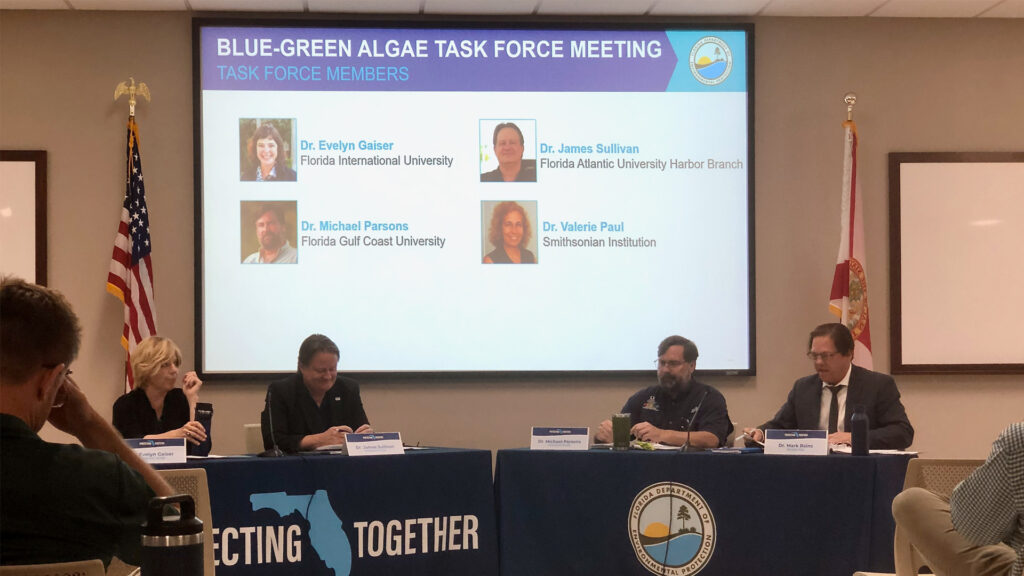

That was one of the main takeaways from the Blue-Green Algae Task Force’s meeting on June 4 at the UF/IFAS North Florida Research & Education Center – Suwannee Valley. The Task Force convened at the center in Live Oak to learn about the science behind Florida’s strategy to manage nutrient pollution from agriculture, the state’s second-largest industry.

The lynchpin of this strategy is a set of tools and techniques known as Best Management Practices, or BMPs. The goal of BMPs is to keep nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus in the soil where they can boost crop growth – and keep them out of water where they can supercharge toxic algae that threaten public health, wildlife and local economies.

Examples of BMPs include using precision irrigation systems, cover crops and controlled release fertilizers. Florida growers in water-impaired regions must either implement BMPs or demonstrate their compliance with state standards through water quality monitoring. The state also offers cost-share assistance to bring BMP investments, such as new equipment, within farmers’ financial reach.

But just how much these practices are reducing nutrient pollution from Florida farms is unclear – and something the Task Force would like to know.

“We would like to know the actual BMP load reduction, what was the actual benefit of that,” said Mark Rains, Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s chief scientific officer, in summarizing the group’s recommendations. “We might need to know what’s happening below the rooting zone, which is unknown in most cases.”

Number of Florida farms out of compliance is unknown

About 60% of Florida’s agricultural lands are registered in the state’s BMP program, said West Gregory, director of Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services’ Office of Agricultural Water Policy. However, FDACS does not know how many farmers are in the state – or how many remain out of compliance. The agency is using tax records to identify unenrolled farmers, Gregory said.

A lack of awareness about the program is one factor in lagging enrollment. FDACS nearly doubled enrollment of growers around the imperiled Indian River Lagoon in one month of outreach this year, adding nearly 18,000 acres, Gregory said.

“There is perception in the public that farmers are a significant source of pollution and that they’re doing nothing about it,” he said. “Quite frankly, they’re doing a lot.”

BMPs ‘not the answer by themselves’

FDACS is also updating the guidelines in its BMP manuals. The University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) is contributing new fertilizer application rates based on advances in research and crop varieties, said Michael Dukes, UF/IFAS associate dean of Extension.

But some Floridians are concerned BMPs are not enough. In the Task Force meeting’s public comment period, Paul Gray, Everglades science coordinator for Audubon Florida, said extensive long-term BMP enrollment around Lake Okeechobee has not produced a measurable improvement in local water quality.

“They’re not really getting us to the goals that we have,” Gray said. “I’m just worried that we’ll improve these manuals, and we’ll spend another 20 years without getting the results that we wish we could get.”

Task Force member Michael Parsons, director of Florida Gulf Coast University’s Coastal Watershed Institute and the Vester Marine and Environmental Science Research Field Station, expressed concerns that, even if farmers adhere to BMPs, water quality targets may remain out of reach, which could require downstream removal of nutrients from waterways.

BMPs are “definitely an important piece of the puzzle,” Parsons told The Invading Sea. “They’re not the answer by themselves.”

Pinpointing solutions that benefit growers and the environment

Growers want to do right by the environment, but can be hesitant to jeopardize productivity in an industry that operates on tight margins, Dukes told The Invading Sea. A 10% decrease in nitrogen fertilizer could mean a 10-fold increased risk to crop yields, he said.

“That’s really the hesitancy,” Dukes said. “It’s the time involved to implement properly. And then whenever it pushes their risk up, they’re very concerned about that because it’s a risky business anyway.”

Farm-scale demonstrations of effective practices could help, said Extension agent Bob Hochmuth, referencing a tool that produced a precise, real-time snapshot of crops’ nutrient needs in the field. The technology led to a 80,000-100,000-pound decrease in nitrogen fertilizer applications in the Suwanee Valley region.

Field-tested methods like these could save farmers money and benefit waterways by preventing over-application of fertilizer.

“It’s the balancing act between profit, efficiency and environmental response,” said Task Force member James Sullivan, executive director of Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute. “Sooner or later, there’s got to be sweet spots in all those.”

Research centers such as the UF/IFAS facility at Live Oak are collecting long-term data on how water and nutrients move through soil to inform future recommendations. Sullivan added that new rules should also account for a changing climate: “You put fertilizer out, well, if we keep on having these massive rainfall events, it just washes into the watershed.”

Multiple sources contribute to Florida’s nutrient problem

Agriculture is not the only source of bloom-powering nutrients. Other sources include stormwater, wastewater, fertilizer runoff from lawns and golf courses and leaky septic tanks.

“There’s as many failing STAs (stormwater treatment areas) and septic systems as there are potentially people who aren’t doing BMPs,” Sullivan told The Invading Sea. “So I would never just point the finger at farmers and say, ‘Oh, it’s their fault.’”

During the public comment period, Mary Hollingsworth said, “The big elephant in the room is the phosphate mining company.”

Natalie van Hoose is a freelance environmental journalist.

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu. To learn more about harmful algal blooms, watch the video below.