By Nina Flores, Columbia University, and Joan A. Casey, University of Washington

Many Americans think of power outages as infrequent inconveniences, but that’s quickly changing. Nationwide, major power outages have increased tenfold since 1980, largely because of an aging electrical grid and damage sustained from severe storms as the planet warms.

At the same time, electricity demand is rising as the population grows and an increasing number of people use electricity to cool and heat their homes, cook their meals and power their cars. A growing number of Americans also rely on electricity-powered medical equipment, such as oxygen concentrators to help with breathing, lifts for movement and infusion pumps to deliver medications and fluids to their bodies.

For older adults and others with health conditions, a loss of power may be more than an inconvenience. It can be life-threatening.

We study environmental health, including the effects of extreme heat and storms on people. In a new study, we analyzed data from New York City and the surrounding area to understand how severe weather drives power outages and who is most at risk, particularly in urban areas.

Low-income communities often at highest risk

How quickly power returns in a community is often shaped by history.

Discriminatory practices such as redlining and zoning, which prevented nonwhite residents from obtaining mortgages or owning homes in certain areas, left marginalized groups living in more disaster-prone areas with poorer quality infrastructure. Studies show that both factors make these communities more likely to experience prolonged power outages.

Current policies can also exacerbate outages for these populations. For example, many electric utilities prioritize power restoration to regions with community assets, such as mass transit, hospitals, police or fire stations, and sewage and water stations, as well as regions with larger populations.

Though these guidelines appear neutral, they can inadvertently prolong outages for less populated areas and areas lacking resources, including these key assets. For example, following Tropical Storm Ida in September 2021, Con Edison outlined areas with important community assets as priorities for restoring power. Manhattan had power back within hours, while many low-income and largely nonwhite parts of Queens, the Bronx and Brooklyn waited for days.

Emerging evidence from studies on power outages in Texas, Florida, the Southeast and a national study, along with our new research in New York, shows that outages especially burden communities that don’t have adequate funding.

Complex weather and battery-life thresholds

Across New York state, we found that 40% of all outages from 2017-2020 followed severe weather – heat, cold, wind, rainstorms, snowstorms or lightning – within eight hours. While each type of severe weather alone could lead to prolonged outages, in combination they resulted in much longer outages.

Statewide, for example, strong winds alone led to outages lasting 12 hours on average, and heavy precipitation resulted in outages lasting six hours on average. But when wind and precipitation happened simultaneously, the outages lasted closer to 17 hours on average.

A six- to eight-hour power-restoration threshold is particularly important for people who rely on electricity to power medical equipment. Many of these medical devices have backup batteries with capacities that do not exceed eight hours. That’s one reason researchers considered eight hours to be a critical power restoration window for health.

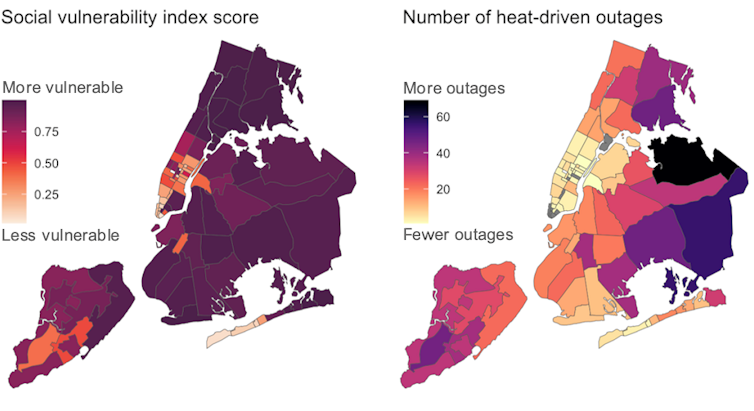

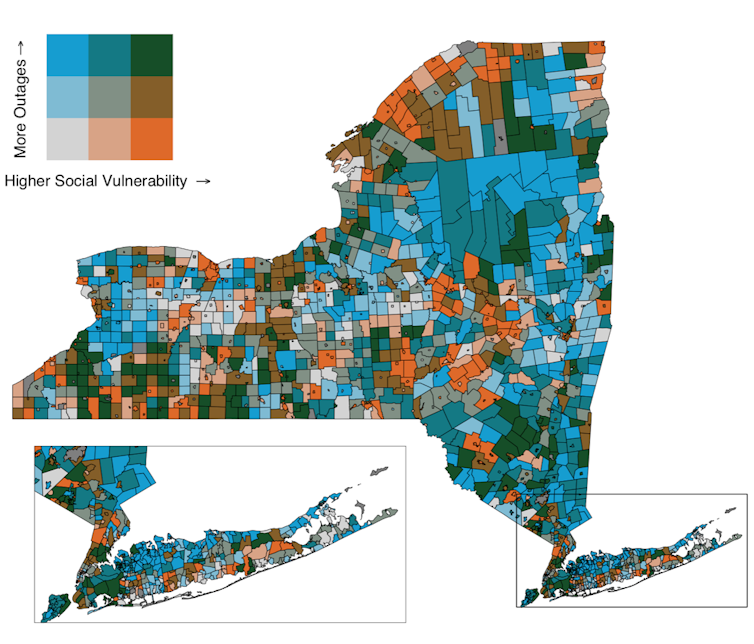

We also looked at whether socially vulnerable communities faced more weather-driven outages than other communities. In short, the answer was yes, though the effects varied in different parts of the state and by the type of weather event.

In New York City, we found that heat-, precipitation- and wind-driven outages occurred more frequently in socially vulnerable communities, including in Harlem, Upper Manhattan, the South Bronx and eastern Queens. This matters because socially vulnerable neighborhoods have higher poverty rates and lower-quality housing. Community members may lack access to health care or suffer from underlying health conditions.

Nina Flores

On average, the duration of precipitation-driven outages was longest in areas of the city with the highest social vulnerability. In neighborhoods with vulnerability scores in the top 25% – meaning the most vulnerable neighborhoods – outages lasted 12.4 hours on average, compared with 7.7 hours in those neighborhoods in the bottom 25%.

In rural parts of the state, outages related to downpours or snowstorms were also longest in areas with high social vulnerability.

Outages are quick to follow heat spikes

As temperatures rise over the summer, it’s important for communities to consider the dangers that outages can present for disabled persons, older adults and others with health conditions, particularly in socially vulnerable communities.

Extreme heat is one of the most dangerous meteorological phenomena. It causes nearly 400 premature deaths a year in New York City, according to city estimates.

With the granular data we obtained from the state Department of Public Service, we could zoom in on how fast outages began following extreme weather.

Across the state, outages began quickly – within six hours of extremely hot temperatures spiking – likely as more people turned on their air conditioners. This means the outages likely occur while it is still hot, exposing individuals to extreme heat, without power for air conditioners or fans.

Nina Flores

Coupled with higher outdoor temperatures and the prevalence of underlying health conditions, socially vulnerable communities face heightened exposure to heat-driven outages and greater risk from them.

How cities can reduce risks as temperatures rise

This outage trend will likely continue as climate change intensifies, bringing more frequent extreme weather to an aging grid in which many parts are nearing or surpassing their life spans.

There are steps communities and power providers can take to reduce people’s exposure to power outages and the health harms that can accompany them.

In the short term, cities can develop targeted plans for these communities to ensure that residents have ways to cool off during heat waves. That includes providing ample cooling centers, swimming pools and public parks with shade trees. It can also include transportation support for older adults and others with mobility issues.

In the long term, reducing these risks means updating the power grid, weatherizing buildings, planting trees to reduce urban heat island effects and investing in distributed energy resources, such as solar power and batteries for energy storage.

We believe this work should prioritize communities that most need these updates, following the lead of New York state’s Weatherization Assistance Program, which aims to improve energy efficiency for low-income households.![]()

Nina Flores, Ph.D., is a student researcher in environmental health at Columbia University and Joan A. Casey is an assistant professor of environmental and occupational health sciences at the University of Washington.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.