By Jenny Staletovich and Patrick Farrell, WLRN News

Deep in the Everglades, in remote sawgrass marshes few people ever see, Michael Frank points to a faded white, red black and gold Miccosukee flag that flies above the dock at his family tree island.

“We were told to never, ever leave the Everglades. You leave the Everglades, you lose your culture, you lose your language, you lose your identity,” Frank said. “You become just like the outside people.”

Today, unnaturally high water flows under the boardwalks that connect the island’s thatch-roofed chickees. Native plants fight for space with weedy elephant grass, Brazilian pepper and other invasive species.

The flag stays up, Frank said, because it represents the Miccosukee Tribe’s willingness to talk with those outside people to help save the marshes that hold his ancestral tree islands.

The WLRN podcast Bright Lit Place examines what happened to Florida’s promise to undo the damage killing the islands and restore the Everglades with a massive plan approved in 2000. Work was originally expected to cost just under $8 billion and take about 20 years. The price has now soared to $23 billion and fallen decades behind schedule. Meanwhile, the swamp keeps dying.

Half the Everglades’ tree islands in Frank’s homeland are now gone, washed away by high water stored in the marshes after the Everglades was dredged and drained to make way for development. Pig Jaw, Smallpox Tommy, Stinking Hammock and other islands where Frank lived and played as a child remain, but they’re chronically threatened by water.

Without freshwater from the Everglades, mangrove forests that protect the shoreline struggle to keep up with sea rise. Spongy peat soils and sawgrass marshes that help collect South Florida’s drinking water continue to collapse. And a menagerie of wildlife, from scarlet-colored roseate spoonbills to marsh rabbits, disappear.

These are some of the people appearing in Bright Lit Place, who’ve spent decades waiting for progress. Those hit hardest measure losses in their checkbooks and family businesses, or even their homelands.

Miccosukee Tribal Elder Michael Frank

Growing up, Frank, 66, lived on tree islands, moving within the swampy patches of high ground shared by the tribe. Even before he was born, the islands were starting to disappear, as the Central and South Florida flood system took shape in the 1940s. The tribe often gathered for celebrations and meetings on a large island called New Town. When the Army Corps dredged a canal to drain farm fields to the north, it split the island in two.

As flood control pushed more water into the vast conservation area west of Miami, Frank was forced to move more frequently. His family finally fled the islands, he said, when the Army Corps dredged a levee near the Tamiami Trail.

“Back in 1949 or ’48, when my grandpa and grandma moved in, that’s when they started working on the levees,” he said. “And when they were working on that, they told my grandfather and grandmother, if that day ever comes when your island goes underwater, we’ll come and build up your camp, which they never did. It went three, four feet under water, but they never came and built the camps up.”

Today, Frank and his uncle still camp on Rice Island, about seven miles north of the Tamiami Trail. He gets around the boardwalks with a walking stick now. Age has left his hands crimped and knotted. He’s had to rebuild his dock as water rises. But he keeps his flags flying.

To hear more from Frank, listen to episode 1 of Bright Lit Place.

Fishing guide Tim Klein

On a postcard perfect day in Florida Bay, fishing guide Tim Klein and his son James steer their boats around a small, horseshoe-shaped key crowded with squawking sea birds.

The water ripples with nervous mullet as a small pod of bottlenose dolphins swim nearby. Suddenly, a dolphin breaks the surface, belly up, with a mullet in its mouth.

“That was epic! Did you see that?” an astonished Klein shouted. “See, I give good eco tour.”

Klein, 62, is a champion flats guide with a long list of tournament victories. Years of poling clients to victory in his skiff kept his schedule booked nearly every day with anglers wanting to catch one of the Keys’ cherished sportfish – bonefish, permit or tarpon.

Fewer days get booked now. When they are, Klein usually suggests a day looking for sawfish or sightseeing around the emerald mangrove islands.

“I got all new clientele,” he said. “I’ve been doing this for 38 years now, and the people I’ve fished in the past are just not here anymore.”

That’s because it’s getting harder to find those champion sportfish in Florida Bay, where flood control has cut off freshwater and left water chronically salty. High salinity can damage seagrass meadows that harbor shrimp, crab and other prey for the fish.

The bay now gets about half of the freshwater it received a century ago.

“It’s never going to be like it used to be back in the days when my dad was guiding, especially with all the big bonefish and scores of red fish,” said James Klein, 23, the third generation of Kleins to captain a boat. He does most of his guiding offshore, not the flats that brought his dad so much success. “We used to drive around on my little Hell’s Bay (skiff) and just find schools of hundreds of them.”

That rarely happens now, he said. And Tim Klein is getting tired of waiting.

“We need to change,” he said. “We keep doing the same thing, year after year after year. It’s always waiting for this project and that project and nothing happens. We just need water some way or another. We need water in our bay before it dies again.”

To hear more from Klein, listen to episode 1 of Bright Lit Place.

Beekeeper Rene Curtis Pratt

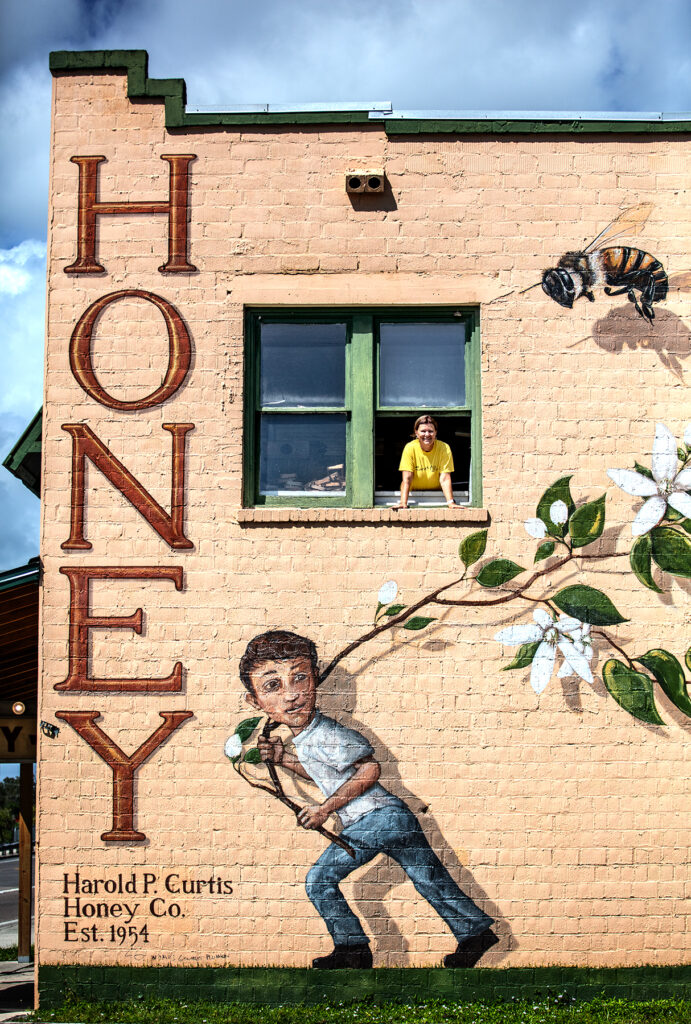

Keg-sized bees hover over windows and honey oozes from a comb on a two-story mural outside the Harold P. Curtis Honey Co. a block from the Caloosahatchee River in tiny LaBelle. Inside, honey is everywhere: in plastic bears and jars, in soaps and candles that line shelves against golden yellow walls.

Rene Curtis Pratt, 65, runs the store her grandfather started nearly 70 years ago. She added the mural a few years ago to highlight the plight of honeybees and the fading industry that once flourished around LaBelle.

Before sugarcane dominated the landscape, cattle and citrus groves filled its saw palmetto prairies. This was the land of juice and honey. Now, it’s a landscape increasingly crowded with planned communities like Timber Creek, Savanna Lakes and Liberty Shores.

Since Hurricane Irma came through in 2017, “this place has exploded,” she said. And that’s bad news for beekeepers.

“People want bees on their property, but yet they don’t want them to sting them or their kids or their horses or their cows,” she said.

It’s another trend getting in the way of restoration. As Florida’s population swelled, housing spread further inland, backing up to the Everglades’ borders. Where farm fields once replaced prairies and wetlands, gated communities now fill fallow fields. All that growth has helped worsen the state’s water problems, with more stormwater and leaking septic tanks fouling Lake Okeechobee and the coastal estuaries connected to it.

Pratt grew up running between her house next to the store and her grandfather’s riverfront house a short walk away.

“We would jump down there and we’d swim in there and there’s gators everywhere. They wouldn’t bother us,” she said. “Now, I wouldn’t get in that river to save my life.”

Last year, Pratt stopped selling her own hive-raised honey in the store and instead buys it from beekeepers with hives located farther away. She also sold that last of her hives.

“I didn’t tell my husband. I didn’t tell my children. Nobody for about six months,” she says, breaking into tears. “And it hurt my heart and my soul.”

To hear more from Pratt, listen to episode 6 of Bright Lit Place.

Bright Lit Place was produced by WLRN News and distributed by the NPR network, with support from the Pulitzer Center’s Connected Coastlines initiative. Click here for part two of this photo essay.

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.