By Hans Nicholas Jong, Mongabay

JAKARTA — The tropics continue to lose primary forest at an alarming rate, with an area of tree cover half the size of Panama disappearing in 2023, new data from the University of Maryland’s GLAD lab show.

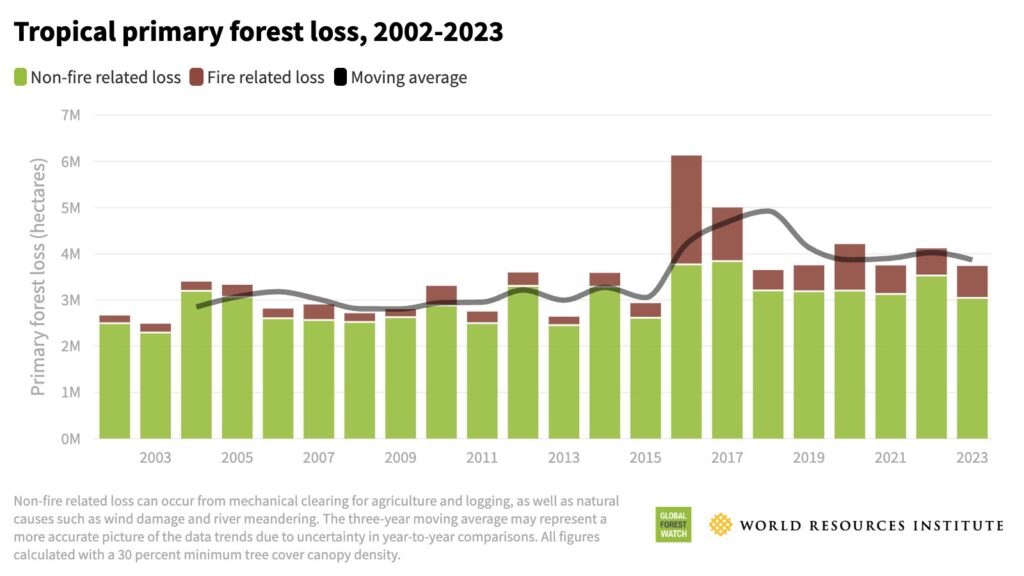

Primary forest loss last year amounted to 3.7 million hectares (9.1 million acres), according to the data, available on the Global Forest Watch (GFW) platform managed by the World Resources Institute (WRI). And while this marks or 9% decrease from 2022, it’s virtually unchanged from the 2019 and 2021 deforestation rates. On average, over the past two decades, the world has consistently lost 3 million to 4 million hectares (7.4 million to 9.9 million acres) of tropical forest every year.

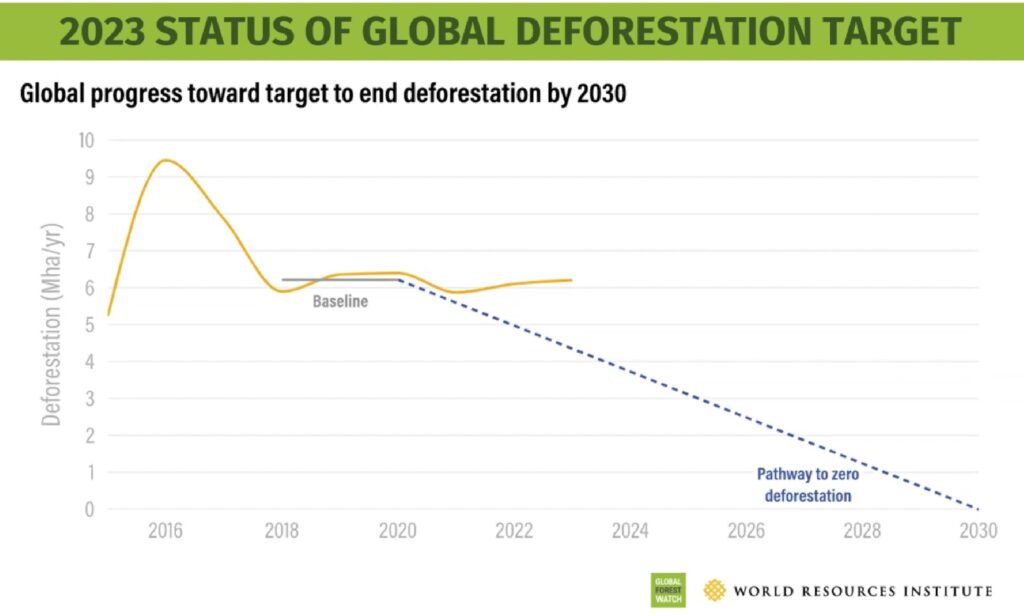

This leaves the planet well off track from achieving zero deforestation by 2030, a global target agreed to by 145 countries at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow in 2021.

Forest loss, particularly in the tropics, releases huge volumes of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Halting and reversing forest loss by the end of the decade is considered essential to meeting the Paris Agreement goal of capping the global average temperature rise at 1.5° Celsius (2.7° Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels.

“Forests are critical ecosystems for fighting climate change, supporting livelihoods and protecting biodiversity,” said WRI president and CEO Ani Dasgupta. “The world has just six years left to keep its promise to halt deforestation. This year’s forest loss numbers tell an inspiring story of what we can achieve when leaders prioritize action, but the data also highlights many urgent areas of missed opportunity to protect our forests and our future.”

Dasgupta was referring to the significant decline of forest loss in Brazil and Colombia as one of the few bright spots coming out of the 2023 data. The WRI attributes the decline there to changes in leadership and policy shifts on forest protection in the two Amazonian countries.

But progress there has been offset by sharp increases in deforestation in tropical countries like Bolivia, Laos and Nicaragua. Other countries also experienced modest increases in forest loss. Outside the tropics, there were also massive increases in forest loss recorded, with Canada experiencing record-breaking fire-related loss.

As a result, the world took “two steps forward, two steps back” in halting forest loss, said GFW director Mikaela Weisse.

“Steep declines in the Brazilian Amazon and Colombia show that progress is possible, but increasing forest loss in other areas has largely counteracted that progress,” she said. “We must learn from the countries that are successfully slowing deforestation or else we will continue to rapidly lose one of our most effective tools for fighting climate change, protecting biodiversity and supporting the health and livelihoods of millions of people.”

Brazil

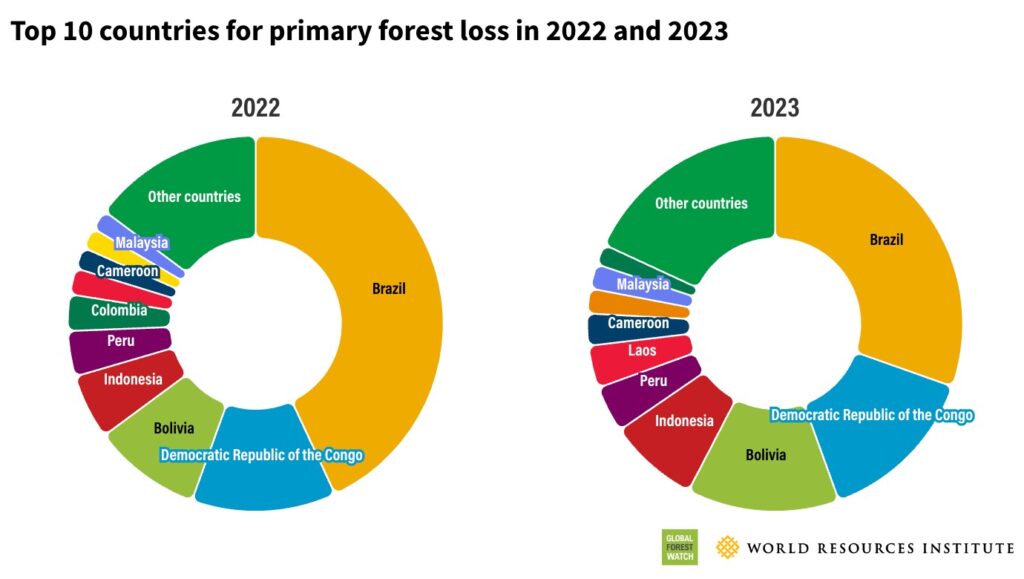

Due to its immense forest area, Brazil continues to have the largest share of tropical primary forest loss, at 1.1 million hectares (2.7 million acres) of loss in 2023.

But that figure represents a 36% reduction in primary forest loss from the previous year, and the lowest level since 2016. This has resulted in a considerable decrease in Brazil’s overall share of total global primary forest loss — down from 43% in 2022 to 30% in 2023.

The reduction in forest loss coincides with President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s first year back in office. Lula already had a track record of dramatically reducing deforestation in the Amazon during his previous terms as a president from 2003-2010, which saw a decrease of 84% between 2004 and 2012.

Since taking office at the start of 2023, Lula has rolled out a number of forest protection policies, such as revoking anti-environmental measures, recognizing new Indigenous territories and bolstering law enforcement efforts. These actions are aimed at undoing the damage done by his predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro, whose administration weakened environmental protections and gutted enforcement agencies. Under Bolsonaro, no new Indigenous lands were recognized and deforestation soared to a 15-year high.

Through his policies, Lula has targeted to end deforestation in the Amazon and Brazil’s other biomes by 2030. The decline in forest loss was strongest in the Amazon, with 39% less primary forest loss in 2023 than in 2022.

“We’re incredibly proud to see such stark progress being made across the country, especially in the Brazilian Amazon,” said Mariana Oliveira, manager of the forests, land use and agriculture program at WRI Brasil.

Yet forest loss in Brazil last year was still nearly double the historical lows of the early 2010s.

“There’s progress in a single year, but a lot more to go to replicate what it’s able to achieve before,” said Matt Hansen, a remote-sensing scientist at the University of Maryland and co-director of the GLAD lab.

And not all Brazilian biomes have seen the same trend as the Amazon, as both the Cerrado grasslands and Pantanal wetlands saw increased forest loss in 2023. The Cerrado, home to the richest biodiversity of any savanna ecosystem in the world, experienced a 6% increase in tree cover loss from 2022 to 2023, continuing a five-year rising trend. The WRI attributed this to agricultural expansion, with the area of Cerrado converted to soy production more than doubling over the past 20 years.

The Pantanal biome, the world’s largest tropical wetland, also saw a spike in forest loss in 2023 due to fires, which have been exacerbated by a multiyear megadrought caused in part by climate change.

While primary forest loss in the Brazilian Amazon has declined, there’s still growing concern that the world’s greatest rainforest is inching closer toward a tipping point — beyond which it will unravel irrevocably into a dry savanna — due to the feedback loops between deforestation, warming temperatures and drought.

Weisse said it’s hard to tell if the Amazon has reached its tipping point just based on the tree cover loss data.

“But we’ve seen this increasingly fire dynamic in Bolivia and the Pantanal biome in Brazil, a shift in fire regime where we see more and more of these fires coming in and repeat burning in some of these areas,” she said. “It’s too early to say if that’s because we’ve reached a tipping point or is there other climate factors involved in that, but it’s an area we’re keeping an eye on.”

Colombia

Colombia is another rare bright spot from 2023, when it lost just 66,000 hectares (163,000 acres) of primary forest, a 49% reduction from 2022.

The WRI noted that the dynamics of forest loss in Colombia are closely intertwined with the country’s peace process. Deforestation rates increased significantly from 2016, when the government signed a peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

For decades, the rebel army had enforced strict limits on logging by civilians, in part to protect their cover from air raids by government forces. After the peace deal, the FARC guerrillas began to demobilize, creating a vacuum in the large tracts of remote forests they once controlled. A land rush quickly followed, with other armed groups, local cattle ranchers and industry groups moving in and promoting illegal logging, mining and cattle ranching.

To address this problem, President Gustavo Petro Urrego, who came into office in August 2022, has initiated peace talks with different armed groups, focused on forest conservation as an explicit goal. Among these groups is Estado Mayor Central (EMC), made up of FARC dissidents, which took the initiative to ban illegal logging in the parts of the Amazon under its control as a “gesture of peace.”

The Petro administration has also pledged to curb annual deforestation, or primary and secondary forest, to 140,000 hectares (346,000 acres) by creating economic alternatives to deforestation and working with Amazonian communities to promote the sustainable management of natural resources and the conservation of forests.

In 2023, Petro also joined other rainforest-rich countries like Brazil, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Indonesia in calling on wealthy nations to finance the conservation of tropical forests, including the Amazon.

According to the WRI, it’s possible that under these policies, deforestation rates in Colombia could return to the lows last seen before the peace agreement.

“The story of deforestation in Colombia is complex and deeply intertwined with the country’s politics, which makes 2023’s historic decrease particularly powerful,” said Alejandra Laina, the manager of natural resources at WRI Colombia. “There is no doubt that recent government action and the commitment of the communities has had a profound impact on Colombia’s forests, and we encourage those involved in current peace talks to use this data as a springboard to accelerate further progress.”

Bolivia, Laos and Nicaragua

At the other end of the spectrum are smaller tropical countries like Bolivia, Nicaragua and Laos, all of which experienced rapid increases in forest loss in 2023, largely due to fires (in the case of Bolivia) and expansion of agricultural land.

In Bolivia, primary forest loss increased by 27%, reaching a record high of 490,500 hectares (1.21 million acres)— the third straight year with a record high. The area lost is also the third most of any tropical country, despite Bolivia having less than half the forest area of either the DRC or Indonesia, the countries with the two largest tropical forest areas after Brazil.

More than half of the forest loss in Bolivia was caused by fires, which are usually set deliberately for agricultural purposes. This was exacerbated by record-breaking heat in 2023 due to the combination of human-caused climate change and the natural El Niño phenomenon.

Agriculture expansion for commodities like soy and beef is the other major driver of forest loss in the country.

Another country that saw record-high forest loss is Laos, which lost 136,500 hectares (337,300 acres) of primary forest in 2023, a 47% increase from the previous record in 2022. This rate of forest loss accounted for 1.9% of Laos’s remaining primary forests and is five times greater than Brazil’s proportional to its forest area.

Agricultural expansion fueled in part by demand and investment by China, the largest importer of agricultural products from Laos, was the main driver of this forest loss. The recent economic downturn in Laos may also a factor, with more people clearing forest for agricultural production, said GFW senior research manager Elizabeth Goldman.

Nicaragua also saw a dramatic increase in forest loss, which in 2023 amounted to 60,000 hectares (148,000 acres) of primary forest, nearly triple the 2022 rate. This means Nicaragua had the highest rate of primary forest loss relative to its size, losing 4.2% of its remaining primary forest in a single year.

“Where’s the end of this kind of high-pressure rate when you talk about 4% on the annual basis in Nicaragua with little forest to begin with?” said UMD’s Hansen.

Like Laos, the forest loss in Nicaragua was largely the result of agricultural expansion, with beef being a major export for the country and much of its production bound for the U.S.

Gold mining is another factor; mining concessions have nearly doubled since 2021 to cover around 15% of the country.

Indonesia

Another tropical country that experienced a significant increase in primary forest loss in 2023 is Indonesia, which lost 292,300 hectares (722,300 acres). That’s up 27% from 2022, the same level of increase as Bolivia.

But unlike Bolivia, which had record-high primary forest loss in 2023, Indonesia’s rate remains well below its historical high from 2016. Forest loss rates in Indonesia have declined sharply since then, hitting a low of 202,900 hectares (501,400 acres) in 2021.

The WRI noted that the UMD statistics on Indonesia are considerably higher than the official Indonesian government numbers due to differences in how primary forest is defined.

Experts predicted that 2023 could see the return of major fire seasons like the ones in 2015 and 2019, but the anticipated impact on forests was less severe impact than initially expected.

“Large areas of Indonesia did burn, but this is more dry and more open landscape in Nusa Tenggara, and some of them are agricultural areas, but not generally in forest,” said WRI global forest director Rod Taylor.

Taylor attributed the less severe fire season in 2023 to the wetter conditions than during the 2015 El Niño, and to investments made by the government in fire prevention capabilities, as well as efforts to suppress fire by local communities.

He said the government “certainly has gotten much stricter in enforcing its laws against fires”.

Companies are also banding together to suppress fires on their concessions, including in Riau province on the island of Sumatra, the center of fire season in Indonesia in recent years.

“[There’s been] amazing collaboration across a wide range of companies on really sophisticated fire response and quick action to prevent fire as soon as it starts,” Taylor said.

Much of the primary forest loss that took place across Indonesia in 2023 was small in scale, less than 100 hectares (250 acres), but added up across several areas. Many of these clearings were the expansion of oil palm, pulpwood and other industrial plantations in Borneo and Papua.

Small clearings for agriculture also contributed to ongoing losses within several protected areas, including Tesso Nilo National Park and Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve in Sumatra, suggesting that smallholders are behind the clearing, Taylor said.

However, U.S.-based NGO Rainforest Action Network (RAN), which has been monitoring expansion of oil palm plantations in Rawa Singkil, said the deforestation in the region is being orchestrated by local elites rather than small farmers, based on the capital required to carry out the clearing. A recent investigation by an association of environmental journalists also found that locals were being paid by monied elites to clear land and plant oil palms in the wildlife reserve.

While Indonesia’s primary forest loss has been consistently low in the past seven years, it’s still too early to tell if this trend will continue in the long run or not, said UMD’s Hansen. This is because change in policies can quickly upend progress, as shown by what happened in Brazil under Bolsonaro.

Indonesia will have a new president in October, with Prabowo Subianto, the country’s defense minister, set to take over from outgoing President Joko Widodo, who has served two consecutive terms. Prabowo has pledged to continue many of Widodo’s policies, including a program aimed at increasing the use of palm oil-based biodiesel.

A 2021 study by the Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR), an Indonesian policy think tank, estimated 4 million to 6 million hectares (10 million to 15 million acres) of land will have to be converted into oil palm plantations to fulfill domestic and export demand for palm biofuel by 2024. That’s in addition to the existing oil palm estate in Indonesia of more than 16 million hectares (40 million acres) — an area the size of Florida.

And with new plantations comes the associated risk of an increase in deforestation, experts warn.

Prabowo has also vowed to proceed with Widodo’s food estate project, which seeks to establish large-scale food crop plantations across the country. Since the start of the program in 2020, multiple reports have found that the program has resulted in the loss of forests, including fragile peatlands.

“So same with Brazil, the question of ephemeral progress in slowing deforestation may not be progress at all,” Hansen said. “We’ll see what happens moving forward.”

DRC

In the Congo Basin, the world’s second-largest expanse of tropical rainforest, the DRC also saw an increase in primary forest loss — a record-high rate of 526,100 hectares (1.3 million acres). The WRI calls the primary forest loss in the DRC “persistently high,” as it has been losing around half a million hectares of primary rainforest each year since 2016.

This is a cause for concern since the Congo Basin is the last major tropical forest that remains a carbon sink, the WRI noted. The basin holds an estimated 29 billion metric tons of carbon in the peat soils that undergird its forests.

The main driver of loss in DRC is shifting cultivation, where land is cleared and burned for the short-term cultivation of crops and left fallow for forests and soil nutrients to regenerate. The cutting and burning of timber to produce charcoal, the dominant form of energy in the DRC, also drives a large chunk of primary forest loss. With 81% of the population not having access to electricity and 62% living on approximately $2 a day, people continue to cut down forests for food and energy.

“Forests are the backbone of livelihoods for Indigenous people and local communities across Africa, and this is especially true in the Congo Basin,” said Teodyl Nkuintchua, the Congo Basin strategy and engagement lead at WRI. “Dramatic policy action must be taken in the Congo Basin to enact new development pathways that support a transition away from unsustainable food and energy production practices, while improving wellbeing for Indigenous people and local communities as much as revenues for countries.”

Canada

Besides analyzing tropical forest loss, the WRI also looked at tree cover loss globally, a trend heavily influenced by annual fire dynamics in the boreal forests of Canada and Russia.

Globally, 28.3 million hectares (70 million acres) of tree cover was lost in 2023, a 24% increase from 2022. Nearly all of this was due to a huge increase in fire-driven tree cover loss in Canada. In the rest of the world, tree cover loss actually decreased overall by 4%.

Canada experienced its worst fire season on record in 2023 due to extensive drought and increased temperatures driven by climate change. As a result, it lost 9 million hectares (22 million acres) of forest, five times more than in 2022, accounting for 63% of global forest loss due to fire.

Hansen called the fires in Canada “a cautionary tale for climate impact.”

Off track

The stubbornly high rates of tropical primary forest loss coupled with fires in boreal forests mean that global deforestation level isn’t dropping to the level needed to halt deforestation by 2030.

A separate analysis by the WRI shows that deforestation in 2023 was almost 2 million hectares (4.9 million acres) above the level needed to be on track to zero deforestation by 2030.

To reach net zero deforestation by 2030, deforestation levels need to be reduced by 10% every year.

“[W]e are far off track and trending in the wrong direction when it comes to reducing global deforestation,” said the WRI’s Taylor.

To rely solely on the political will of leaders like Lula in Brazil isn’t enough, as progress can be reversed when political winds change, he said.

“So to sustain reduced deforestation rates, the global economy needs to increase the value of standing forests relative to the short-term gains on offer from clearing forests to make way for farms, mines, or new roads,” Taylor said.

Some promising ways to achieve this include performance-based payments like REDD+, which reward forest protection restoration by valuing forests for the carbon they store, the water they regulate, or their biodiversity, he said.

Another mechanism is regulatory or voluntary measures to eliminate deforestation from commodity supply chains, Taylor said.

Securing the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities living in and around forests and empowering them to pursue economic activities that can be sustained within healthy forests and rivers is also crucial to protect forests, he said.

“So bold global mechanisms and unique local initiatives together are both needed to achieve enduring reductions in deforestation across all tropical front countries,” Taylor said.

Mongabay is a U.S.-based nonprofit conservation and environmental science news platform. This piece was originally published at https://news.mongabay.com/2024/04/tropical-forest-loss-puts-2030-zero-deforestation-target-further-out-of-reach/.

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.