By Thomas F. Ries, Ecosphere Restoration Institute

Florida’s low elevations, especially along the coast, make the state especially vulnerable to flooding. This fact, coupled with the historic extensive filling of bays and waterways to create waterfront properties, resulted in excessive hardening of these shorelines.

There has been a strong push to replace these overhardened shorelines with nature-based design solutions, such as living shorelines. But there are limitations on being able to restore a more natural shoreline within manmade canals due to physical constraints such as the proximity to adjacent infrastructure.

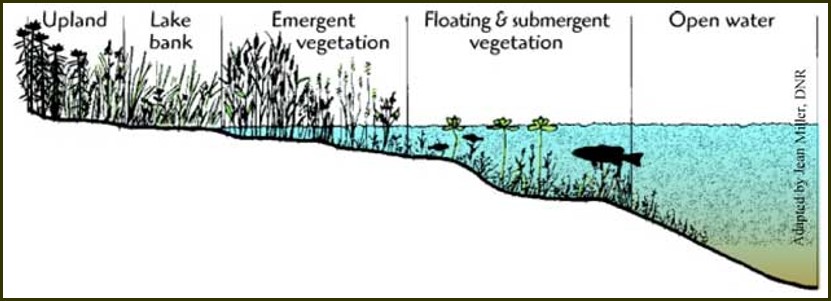

A nature shoreline is comprised of a gentle slope starting in the upland area and transitioning down to the deep water; the area in between is where natural life exists. These important transitional areas are what is lost when we insert a seawall. These seawalls result in more turbid water since they transfer the wave energy down, which resuspends sediment into the water column, blocks light from reaching the bottom and inhibits seagrass growth.

In many locations, living shorelines are used to replace failing seawall structures, which results in improved ecosystem functions. If properly designed, they will never need to be replaced. Plus, the restored life and associated ecosystem services can naturally migrate upslope in response to sea-level rise.

In over-engineered situations where there are seawalls in areas where there is no wave energy to dissipate, these structures can be completely removed and replaced with living shorelines or even with living seawalls. A living seawall is employed in sites that have very limited space to recreate a gradual slope like a nature shoreline.

In those cases, the seawall is left in place and some of the ecosystem services can be achieved by placing rock in front of the seawall. By just adding this rock at the toe of the seawall, the situation improves two-fold: By reducing the resuspension of sediments and providing protection to the seawall itself to prolong its life. In most cases this added rock can also include a sediment tube that can be planted with native vegetation to recreate habitat for fish, crabs and other wildlife.

The amount of material that can be placed in front of an existing seawall is dependent upon the depth of the water and sediment type. In shallow water areas it can be a very thin line of rock within 10 feet of the seawall, or it could be larger, which means additional permitting requirements. These living seawall features can then be planted with native marsh grass or even mangrove trees.

Often the thought of planting mangroves is a concern as they will grow into trees that could hinder or even block the view of the water. These planted mangroves can be trimmed to preserve the viewshed. In most cases by the time they are tall enough to start to obscure the view they are already providing ecosystem services, so keeping them at that height is allowable and beneficial.

These living seawalls are not the perfect solution, as the seawall is still in place and it is difficult for the newly created planted areas to migrate upslope in response to sea-level rise. However, they do provide ecological benefits for the short term (20-35 years).

It is important to note that each site is somewhat unique and so the ultimate design approach is site specific. Finally, it is imperative that the remaining seawall be assessed to determine the life of this structure and to consider raising it to the recommended elevation (5-foot NAVD), which will provide protection to the adjacent infrastructure (home or business) through at least 2050, per the latest sea-level rise predictions.

These living seawalls help to preserve property values while improving aesthetics. In a small way they help our juvenile fish populations by providing physical cover and a place for them to hide from their predators.

However, currently there are no easy regulatory permitting pathways to implementing these unique design features. There are also additional upfront costs, which deter folks from implementing these design options.

Progress to help streamline the permitting process is being made by federal and local regulatory agencies to try and encourage these design approaches, with the hope that more living shorelines and livings seawalls are installed.

Thomas F. Ries is president of the Ecosphere Restoration Institute, a nonprofit organization based in Largo.

If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu. Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here.

it could take up to 50 years to grow a mature mangrove…..