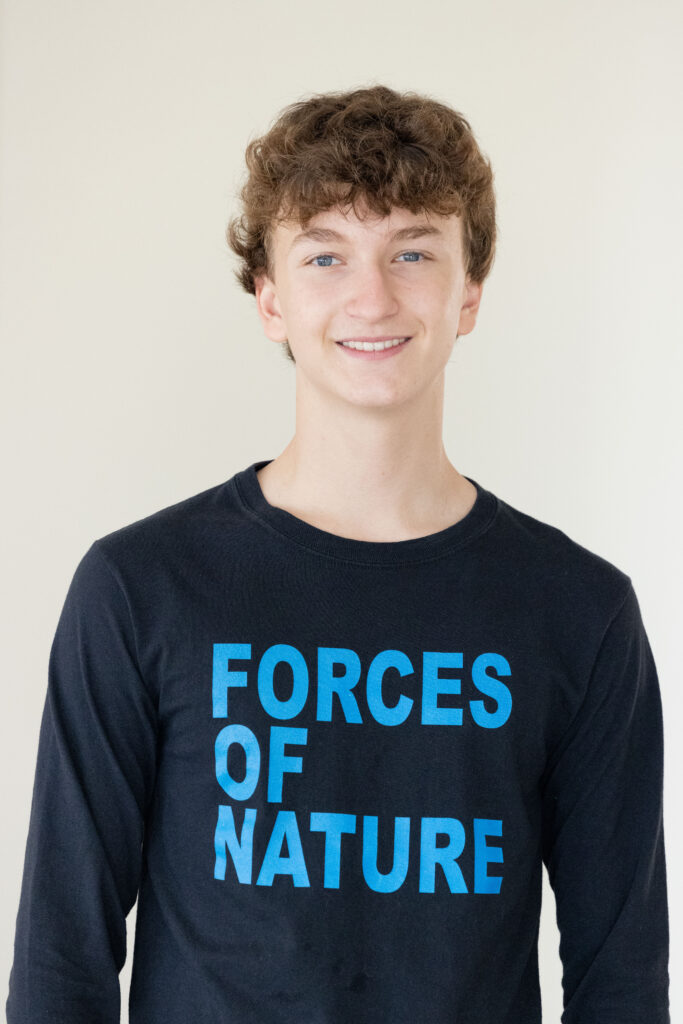

By Will Charouhis, age 17, founder of We Are Forces of Nature

DUBAI, United Arab Emirates — With negotiations complete at the United Nations international climate conference, billed as the “best last chance” to save our planet, the eyes of history will look back on this moment. Climate negotiators from 197 countries, who convened in Dubai to save the planet, burst into applause as the final text of what has been labeled as the UAE Consensus was formally adopted. After two long weeks of negotiations that stretched into overtime as lead negotiators rushed to save humanity from itself, two ostensibly historic agreements were reached.

At the outset of the conference, wealthy countries pledged over $750 million to finance climate-related losses in developing countries. And in the last hours of a conference rift with infighting among the world’s petrostates, 197 countries came together to reach an agreement 30 years in the making to begin phasing down fossil fuels.

But as world leaders took to the stage to snap final photo-ops, the leaders of the Marshall Islands and the Seychelles packed away their computers, silent in the knowledge that without an operationalized Loss and Damage Fund and an immediate end to fossil fuel extraction, the loopholes in the agreed-upon text seal their fate. Late to arrive at the final plenary, the Alliance of Small Island States, a coalition of 39 nations particularly vulnerable to the climate emergency, were working hard to propose a more ambitious text and were not in the room when the final deal was reached.

And as exultant negotiators made a fast break for the exits, the grim faces of the youth lining the hall outside the conference room told another story. Here to do our best to hold world leaders accountable to take action to ensure a livable planet, as the cacophony of COP28 comes to an end, there is a sense of peril that the promises made here today are too little, too late.

Amid the splashy press releases of the launch of the Loss and Damage Fund, little mention was made that the promised funds are pledges, not deposits, and that one-time monetary commitments fall far short of the estimated $400 billion in losses developing countries face annually. Almost no mention was made that the offers are for financing, not grants, and may be well beyond the reach of debt-laden poor nations. And missing from the agreement to phase out fossil fuels are any powers of enforcement. The commitments are voluntary, and allow for reliance on carbon removal and storage technologies, innovations that engineers predict will never be of sufficient scale to capture the carbon we need to bring down the heat.

It remains to be seen whether the decisions made at COP28 in the heart of the UAE will gain teeth. The last hugely historical climate text was the Paris Agreement. Reached at COP15, countries promised then to work toward a target of limiting global warming to no more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, the maximum temperature predicted by scientists to keep the world habitable. Yet despite planet-savers’ best efforts, emissions have continued to climb, the Earth remains on track for 3°C warming and 2024 will close out as the hottest year in recorded history. So youth question whether this UAE Consensus, making headlines across the globe, will be the game-changer we need to slow climate change.

Yet amidst the hazy blanket of smog that smothered Dubai during much of the conference, there were moments of irrefutably positive change. I had the opportunity to serve on the opening panel at the Children and Youth Pavilion, the second year in a row where the youth were given a designated space to raise our voice.

The pavilion touted that the UAE had funded more than 1,000 young adults to attend the conference from developing countries. Humbled to be included as the American voice on a panel at the Nepal Pavilion, my new Nepalese friends proudly announced this was the first year their impoverished country was able to secure a pavilion of their own. And while there was much negative press about the 2,500 gas and oil lobbyists at COP28, the unspoken good news is that the conference was patently diverse, with countries from the Global South sending some of the largest delegations. The UAE promised to hear every voice, and slowly those once marginalized appear to be gaining an audience.

But as I leave Dubai, I wonder whether anybody’s really listening. Far from the celebrations in this gilded city, hundreds have died at the same time in small villages in Kenya, Somalia, Ethiopia and Tanzania due to unprecedented flooding caused by record rainfall due to climate change.

So I’ll wait anxiously with the rest of the world to see whether public will and political might will give life to the words on the page. The words are not enough, and they have come too late for many, but they are a start.

And I remind myself that we come to these conferences asking for countries to make policy decisions to keep fossil fuels in the ground. Yet, in the end, aren’t the decisions really ours? Fossil fuel supply is driven by our demand. We, the people, control that. History starts now. And it’s our narrative to write. So let’s get busy.

Will Charouhis is a 17-year-old climate activist from Miami. Leading one of the world’s youngest non-governmental delegations at COP28, he is the founder of We Are Forces of Nature, a youth-led organization aiming to slow climate change. He can be reached at volunteer@weareforcesofnature.org.

If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu. Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here.

Amazing and this Will Charouhis amazing