By Michael Childress, Clemson University

Armed with scrub brushes, young scuba divers took to the waters of Florida’s Alligator Reef in late July to try to help corals struggling to survive 2023’s extraordinary marine heat wave. They carefully scraped away harmful algae and predators impinging on staghorn fragments, under the supervision and training of interns from Islamorada Conservation and Restoration Education, or I.CARE.

(Credit: NOAA)

Normally, I.CARE’s volunteer divers would be transplanting corals to waters off the Florida Keys this time of year, as part of a national effort to restore the Florida Reef. But this year, everything is going in reverse.

As water temperatures spiked in the Florida Keys, scientists from universities, coral reef restoration groups and government agencies launched a heroic effort to save the corals. Divers have been in the water every day, collecting thousands of corals from ocean nurseries along the Florida Keys reef tract and moving them to cooler water and into giant tanks on land.

Marine scientist Ken Nedimyer and his team at Reef Renewal USA began moving an entire coral tree nursery from shallow waters off Tavernier to an area 60 feet deep and 2 degrees Fahrenheit (1.1 Celsius) cooler. Even there, temperatures were running about 85 to 86 F (30 C).

Their efforts are part of an emergency response on a scale never before seen in Florida.

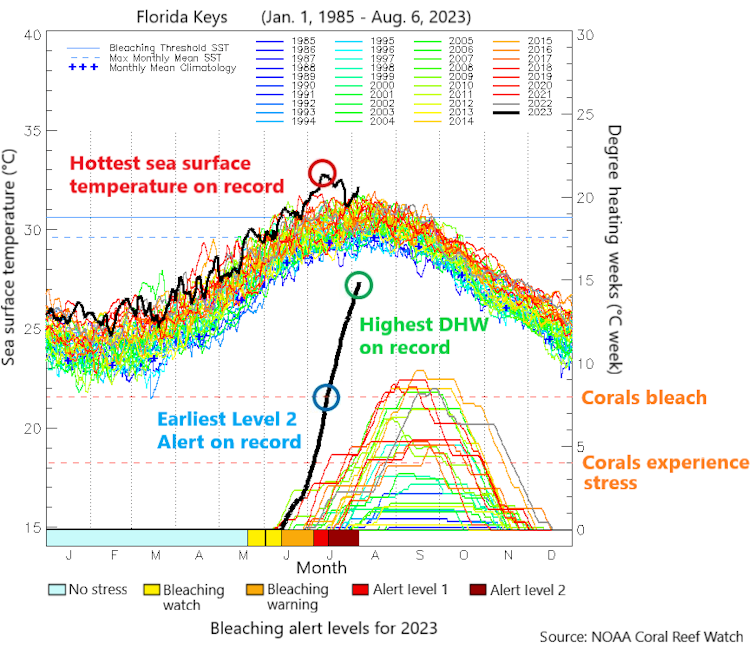

The Florida Reef – a nearly 350-mile arc along the Florida Keys that is crucial to fish habitat, coastal storm protection and the local economy – began experiencing record-hot ocean temperatures in June 2023, weeks earlier than expected. The continuing heat has triggered widespread coral bleaching.

While corals can recover from mass bleaching events like this, long periods of high heat can leave them weak and vulnerable to disease that can ultimately kill them.

That’s what scientists and volunteers have been scrambling to avoid.

The heartbeat of the reef

The Florida Reef has struggled for years under the pressure of overfishing, disease, storms and global warming that have decimated its live corals.

A massive coral restoration effort – the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Mission: Iconic Reef – has been underway since 2019 to restore the reef with transplanted corals, particularly those most resilient to the rising temperatures. But even the hardiest coral transplants are now at risk.

Reef-building corals are the foundation species of shallow tropical waters due to their unique symbiotic relationship with microscopic algae in their tissues.

During the day, these algae photosynthesize, producing both food and oxygen for the coral animal. At night, coral polyps feed on plankton, providing nutrients for their algae. The result of this symbiotic relationship is the coral’s ability to build a calcium carbonate skeleton and reefs that support nearly 25% of all marine life.

Unfortunately, corals are very temperature sensitive, and the extreme ocean heat off South Florida, with some reef areas reaching temperatures in the 90s, has put them under extraordinary stress.

When corals get too hot, they expel their symbiotic algae. The corals appear white – bleached – because their carbonate skeleton shows through their clear tissue that lack any colorful algal cells.

Corals can recover new algal symbionts if water conditions return to normal within a few weeks. However, the increase in global temperatures due to the effects of greenhouse gas emissions from human activities is causing longer and more frequent periods of coral bleaching worldwide, leading to concerns for the future of coral reefs.

A MASH unit for corals

This year, the Florida Keys reached an alert level 2, indicating extreme risk of bleaching, about six weeks earlier than normal.

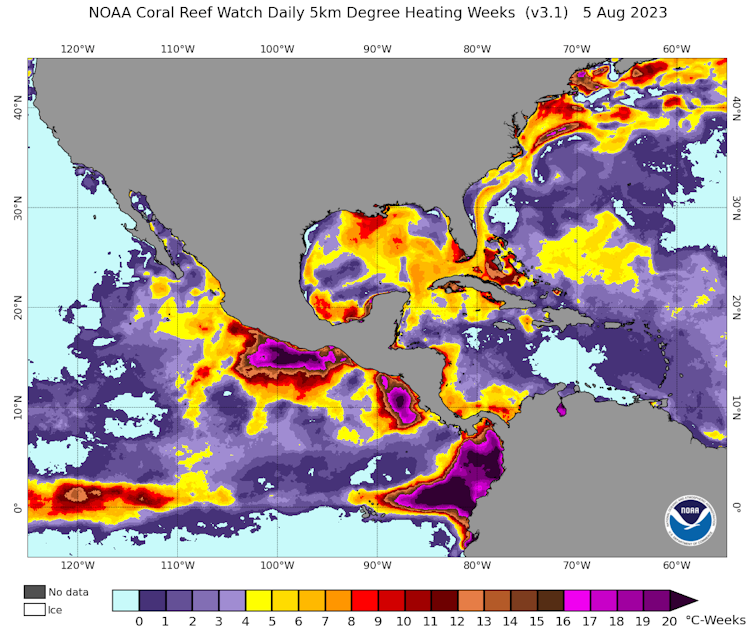

The early warnings and forecasts from NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch Network gave scientists time to begin preparing labs and equipment, track the locations and intensity of the growing marine heat and, importantly, recruit volunteers.

Adapted from NOAA

At the Keys Marine Laboratory, scientists and trained volunteers have dropped off thousands of coral fragments collected from heat-threatened offshore nurseries. Director Cindy Lewis described the lab’s giant tanks as looking like “a MASH unit for corals.”

Volunteers there and at other labs across Florida will hand-feed the tiny creatures to keep them alive until the Florida waters cool again and they can be returned to the ocean and eventually transplanted onto the reef.

NOAA Coral Reef Watch

Protecting corals still in the ocean

I.CARE launched another type of emergency response.

I.CARE co-founder Kylie Smith, a coral reef ecologist and a former student of mine in marine sciences, discovered a few years ago that coral transplants with large amounts of fleshy algae around them were more likely to bleach during times of elevated temperature. Removing that algae may give corals a better chance of survival.

Smith’s group typically works with local dive operators to train recreational divers to assist in transplanting and maintaining coral fragments in an effort to restore the reefs of Islamorada. In summer 2023, I.CARE has been training volunteers, like the young divers from Diving with a Purpose, to remove algae and coral predators, such as coral-eating snails and fireworms, to help boost the corals’ chances of survival.

Monitoring for corals at risk

(NOAA AOML)

To help spot corals in trouble, volunteer divers are also being trained as reef observers through Mote Marine Lab’s BleachWatch program.

Scuba divers have long been attracted to the reefs of the Florida Keys for their beauty and accessibility. The lab is training them to recognize bleached, diseased and dead corals of different species and then use an online portal to submit bleach reports across the entire Florida Reef.

The more eyes on the reef, the more accurate the maps showing the areas of greatest bleaching concern.

Rebuilding the reef

While the marine heat wave in the Keys will inevitably kill some corals, many more will survive.

Through careful analysis of the species, genotypes and reef locations experiencing bleaching, scientists and practitioners are learn valuable information as they work to protect and rebuild a more resilient coral reef for the future.

That is what gives hope to Smith, Lewis, Nedimyer and hundreds of others who believe this coral reef is worth saving. Volunteers are crucial to the effort, whether they’re helping with coral reef maintenance, reporting bleaching or raising the awareness of what is at stake if humanity fails to stop warming the planet![]()

Michael Childress is an associate professor of biological sciences and environmental conservation at Clemson University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.