By Karen D. Holl, University of California, Santa Cruz; and Pedro Brancalion, Universidade de São Paulo

For 151 years, Americans have marked Arbor Day on the last Friday in April by planting trees.

Now business leaders, politicians, YouTubers and celebrities are calling for the planting of millions, billions or even trillions of trees to slow climate change.

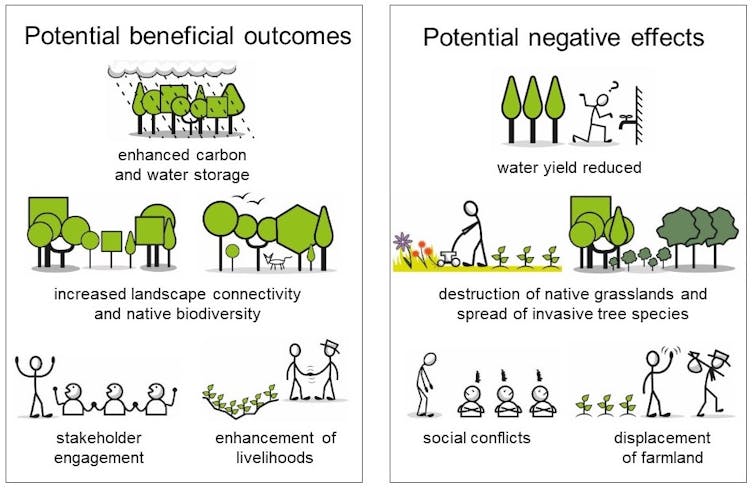

As ecologists who study forest restoration, we know that trees store carbon, provide habitat for animals and plants, prevent erosion and create shade in cities. But as we have explained elsewhere in detail, planting trees is not a silver bullet for solving complex environmental and social problems. And for trees to produce benefits, they need to be planted correctly – which often is not the case.

Vanessa Sontag, modified from Holl and Brancalion 2020., CC BY-ND

Tree-planting is not a panacea

It is impossible for humanity to plant its way out of climate change, as some advocates have suggested, although trees are one part of the solution. Scientific assessments show that avoiding the worst consequences of climate change will require governments, businesses and individuals around the globe to make rapid and drastic efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Moreover, planting trees in the wrong place can have unintended consequences. For example, planting trees into native grasslands, such as North American prairies or African savannas, can damage these valuable ecosystems.

Robin Chazdon, CC BY-ND

Planting fast-growing, nonnative trees in arid areas may also reduce water supplies. And some top-down tree-planting programs implemented by international organizations or national governments displace farmers and lead them to clear forests elsewhere.

Large-scale tree-planting initiatives have failed in locations from Sri Lanka to Turkey to Canada. In some places, the tree species were not well suited to local soil and climate conditions. Elsewhere, the trees were not watered or fertilized. In some cases local people removed trees that were planted on their land without permission. And when trees die or are cut down, any carbon they have taken up returns to the atmosphere, negating benefits from planting them.

Focus on growing trees

We think it’s time to change the narrative from tree-planting to tree-growing. Most tree-planting efforts focus on digging a hole and putting a seedling in the ground, but the work doesn’t stop there. And tree-planting diverts attention from promoting natural forest regrowth.

To achieve benefits from tree-planting, the trees need to grow for a decade or more. Unfortunately, evidence suggests that reforested areas are often recleared within a decade or two. We recommend that tree-growing efforts set targets for the area of forest restored after 10, 20 or 50 years, rather than focusing on numbers of seedlings planted.

And it may not even be necessary to actively plant trees. For example, much of the eastern U.S. was logged in the 18th and 19th centuries. But for the past century, where nature has been left to take its course, large areas of forests have regrown without people’s planting trees.

David Foster/Harvard Forest, CC BY-ND

Helping tree-growing campaigns succeed

Tree-growing is expected to receive unprecedented financial, political and societal support in the coming years as part of the U.N. Decade on Ecosystem Restoration and ambitious initiatives such as the Bonn Challenge and World Economic Forum 1t.org campaign to conserve, restore and grow 1 trillion trees. It would be an enormous waste to squander this unique opportunity.

Here are key guidelines that we and others have proposed to improve the outcomes of tree-planting campaigns.

Keep existing forests standing. Global Forest Watch, an online platform that monitors forests around the world, estimates that the Earth lost an area of rainforest the size of New Mexico in 2020. It is much more effective to prevent clearing of existing forests than to try to put them back together again. And existing forests provide benefits now, rather than decades into the future after trees mature.

Protecting existing forests often requires providing alternative income for people who maintain trees on their land rather than logging them or growing crops. It also is important to strengthen enforcement of protected areas, and to promote supply chains for timber and agricultural products that do not involve forest-clearing.

Include nearby communities in tree-growing projects. International organizations and national governments fund many tree-growing projects, but their goals may be quite different from those of local residents who are actually growing the trees on their land. Study after study has shown that involving local farmers and communities in the process, from planning through monitoring, is key to tree-growing success.

Pedro Brancalion, CC BY-ND

Start with careful planning. Which species are most likely to grow well given local site conditions? Which species will best achieve the project’s goals? And who will take care of the trees after they are planted?

It is important to plant in areas where trees have grown historically, and to consider whether future climatic conditions are likely to support trees. Planting in areas that are less productive for agriculture reduces the risk that the land will be recleared or existing forests will be cut down to compensate for lost productive areas.

Plan for the long term. Most tree seedlings need care to survive and grow. This may include multiyear commitments to water, fertilize, weed and protect them from grazing or fire and monitor whether the venture achieves its goals.

We recently published a list of questions that all tree-growing organizations should answer and that funders should ask before pulling out their wallets. They include questions about whether the initial drivers of deforestation have been addressed, how the project will be maintained and monitored over time, and how local stakeholders will be involved and benefit from the project. It’s also important to look at the outcomes of prior tree-growing projects overseen by the organization.

Organizations that follow best practices are much more likely to grow trees successfully over the long term. Planting seedlings is just the first step.

This is an update of an article originally published on April 27, 2021.![]()

Karen D. Holl is a professor of restoration ecology at the University of California, Santa Cruz; and Pedro Brancalion is a professor of forest restoration at Universidade de São Paulo.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.