By Nathan Crabbe

As Florida’s population continues growing and sea levels continue rising, the state risks losing millions of acres of agricultural and natural land to development.

A new study outlines alternate scenarios of where development might happen in Florida by 2040 and 2070, based on whether the state allows unchecked urban sprawl or commits to land conservation. The joint project comes from the University of Florida Center for Landscape Conservation Planning and 1000 Friends of Florida, a nonprofit group that advocates for smart-growth policies.

Florida is uniquely vulnerable to rising seas due to its hundreds of miles of coastline and low-lying topography, said Paul Owens, president of 1000 Friends of Florida. The project looks at how sea-level rise compounds development pressure from population growth, Owens said, as well as how state and local governments might respond through their growth policies.

“Decisions made through land-use planning typically take years to play out,” he said, “so if we want to prepare responsibly and effectively for sea-level rise over those 20-year and 50-year horizons, we need to get started right away.”

The study anticipates that both Florida’s population and sea-level rise will continue to increase significantly. The state’s population is projected to rise to 26.4 million by 2040, a 21% increase over 2021, and to 33.7 million by 2070, according to Florida Bureau of Economic and Business Research figures.

At the same time, sea levels are projected to rise by about 10 inches by 2040 and nearly 3 feet by 2070, according to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration figures.

The study looks at where residents of land lost to sea-level rise might relocate and new residents might live, based on two alternate scenarios. A “sprawl” scenario assumes the same densities and patterns of development continuing as the population grows, while a “conservation” scenario assumes that new development will be more compact, greater redevelopment will happen in urban areas and high-priority natural land will be protected.

“In terms of future population, we can accommodate the same number of people in a smaller footprint and actually have more land protection and maintain our agricultural lands and our agricultural production, just by making smarter, more strategic decisions about land use and density and where those type of things occur,” said Mike Volk, associate director of the UF Center for Landscape Conservation Planning.

The study found that by 2040, a “conservation” scenario would result in 270,000 fewer acres of developed land, 5 million more acres of undeveloped priority natural land and 2.4 million more acres of protected agricultural lands. By 2070, it would mean 1.3 million fewer acres of developed land and 7.3 million more acres of protected natural and agricultural lands than the “sprawl” scenario.

The report’s recommendations include calling on Florida to redirect development away from vulnerable areas, promote more compact development patterns and recommit to significant investment in land conservation. Project members said land conservation provides benefits such as preventing flooding and protecting the drinking water supply.

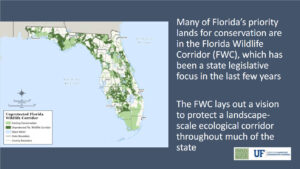

Tom Hoctor, director of the UF Center for Landscape Conservation Planning, said state lawmakers have focused on protecting the Florida Wildlife Corridor in recent years as funding for land conservation has rebounded to about $300 million annually. But Hoctor said the state must spend at least that much each year in order to protect the corridor and other conservation priorities.

“We need that to continue for at least several decades, so it needs to be a long-term commitment,” he said.

Owens said the uptick in land conservation spending has coincided with the tenure of Gov. Ron DeSantis, who also issued an executive order in January that included a call for sustainable growth and expediated land conservation. Owens applauded those goals, but said the Legislature must follow through on them

“Potentially if the Legislature does follow that lead, we could be … an example here in Florida that a candidate for national office could point to with some pride,” he said.

More information on “Florida’s Rising Seas: Sea Level 2040 & Sea Level 2070” can be found on the project’s website, https://1000fof.org/sealevel2040/.

Nathan Crabbe is editor of The Invading Sea. He can be reached at ncrabbe@fau.edu.