By Eric Eikenberg, Everglades Foundation

The South Florida Water Management District recently approved a $14 million contract that could ultimately lead to 80 water storage wells being dug deep into the limestone aquifer north of Lake Okeechobee.

The District wisely appears to be moving cautiously, approaching this with a transparent, science-based plan that responds to concerns raised by the National Academy of Sciences.

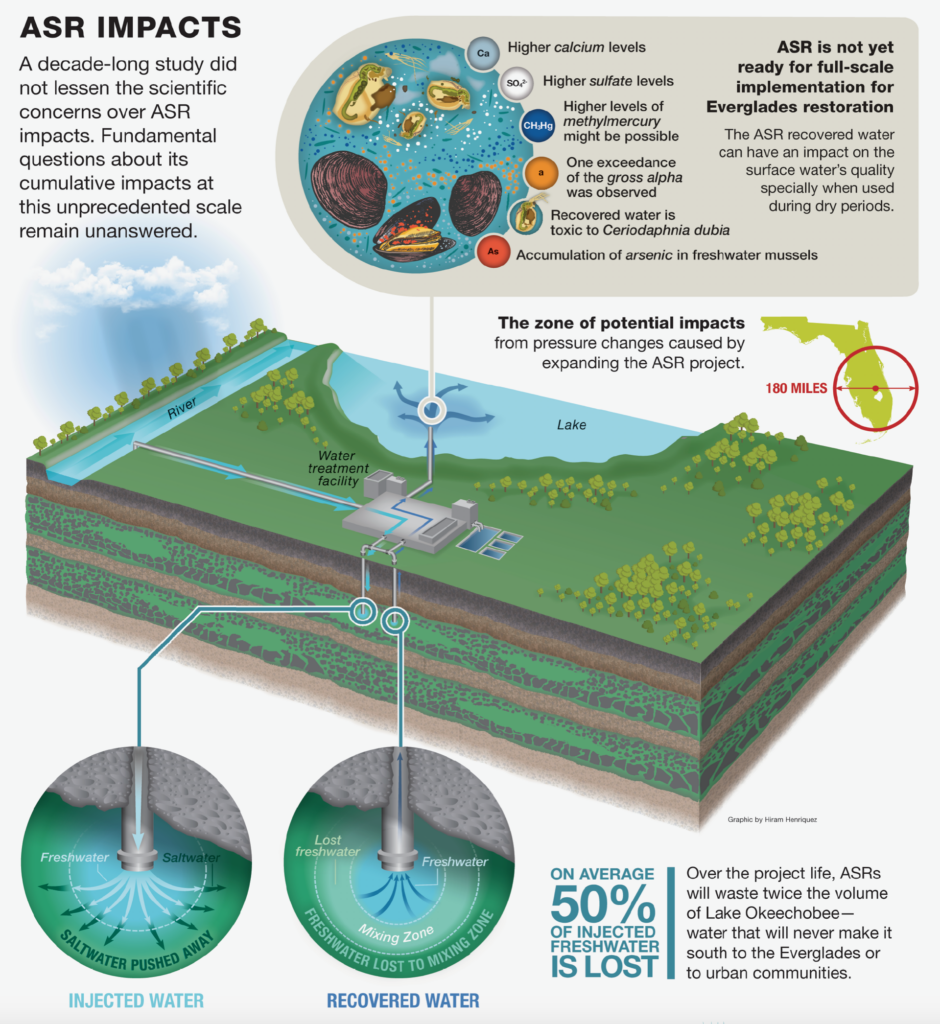

These “aquifer storage and recovery wells” would pump excess water a quarter mile underground to lower Lake Okeechobee water levels, with only about half of it to be retrieved later. Recovered water would be used primarily to replenish the lake, meet agricultural needs, and rehydrate nearby wetlands.

The 2000 Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan initially called for an extraordinary 333 wells, with the goal of holding 20 times more water than the world’s largest storage site of its kind.

In response, the District and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers identified several issues to be addressed before the project could go forward.

A plan was developed to conduct five pilot studies to examine the suitability of the technology for ecological restoration, but because of funding shortages only two of the test sites were ever constructed.

Although the pilot studies resolved many questions about the technology, the National Academy of Sciences warned that they raised several new concerns and left unanswered the potential risk of introducing toxins into sensitive wetlands.

Even with a pared-back plan with fewer wells, uncertainties about their ecological effects are still too great to justify near-term, large-scale implementation, the Academy cautioned.

Problems were exposed at every stage of the process: the quality of the water injected into the aquifer, the impact of the water on the aquifer (and vice versa), and the effects of the recovered water on the environment.

Injecting water that is already polluted with high levels of iron, organic compounds and oxygen into the aquifer is a recipe for disaster, but water injected at the two pilot sites commonly contained bacteria and parasite indicators of human pathogens.

The recovered water failed some toxicity tests and had an adverse impact on the surface water, affecting the reproduction of some species of aquatic animals. Other species showed evidence of arsenic buildup.

Pilot testing was unable to resolve other issues related to water quality including levels of calcium, sulfate and phosphorus in the recovered water. Some claim that phosphorus levels in the recovered water were actually lower, but the National Academy of Sciences cautioned that there is no agreement on whether this is a temporary, short-term effect or the result of an actual containment of pollution within the aquifer.

Before proceeding further, the Academy recommended additional studies to examine possible methods to reduce concentrations of arsenic, trace metals and sulfate. Sulfate is an important chemical that might lead to the harmful bioaccumulation of mercury in animals throughout the Everglades.

Both the Army Corps of Engineers and the National Academy of Sciences also identified serious questions about cost. Over the life of the project, the 80 wells planned for north of Lake Okeechobee will waste more than twice the volume of the lake itself, making alternatives such as above ground storage reservoirs potentially more cost-effective.

Before any large-scale implementation takes place, the National Academy of Sciences recommended a thorough testing and evaluation phase including modeling, laboratory experiments and additional pilot testing.

None of the recommended testing has occurred in the intervening five years. Although the District’s planned coring and monitoring wells (which are pre-requisites to further construction) may address some of the questions raised, what’s been lacking is a clear and transparent, science-based methodological process to protect the ecosystem and the public.

Happily, the Water District now appears positioned to approve just such a process — a “go or no-go” science plan that can ensure that each of these critical issues is resolved before work proceeds.

This is a welcome change from the way we have addressed Florida’s water issues in the past — with a “know-it-all” approach that we are all paying for now. With every well-intentioned effort came unanticipated consequences that caused new problems and the “solutions” generated a whole new set of complications.

Without a specific, science-based plan to evaluate the consequences of this project, to borrow from Stuart Applebaum, the former Army Corps of Engineers Deputy for Restoration Program Management, the aquifer storage and recovery wells would be exactly like the Apollo mission – except that we won’t know where the moon is, or how to find it, or whether it is made of green cheese.

Eric Eikenberg is CEO of The Everglades Foundation.

“The Invading Sea” is the opinion arm of the Florida Climate Reporting Network, a collaborative of news organizations across the state focusing on the threats posed by the warming climate.